|

One

of the most prestigious office complexes on Manhattan Island,

Rockefeller Center is the centerpiece of activity for thousands of New

Yorkers who have embraced it as not just another boring office block,

but as a warm symbol of a great city. Its rise to national stardom came

not so much from the historic name it bears, but because for almost as

long as there has been broadcasting, Rockefeller Center has been the

home to some of the most powerful networks in the United States. The

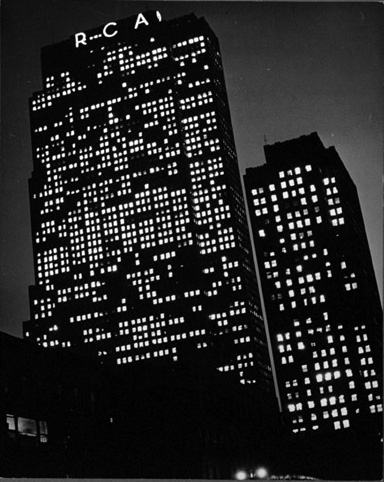

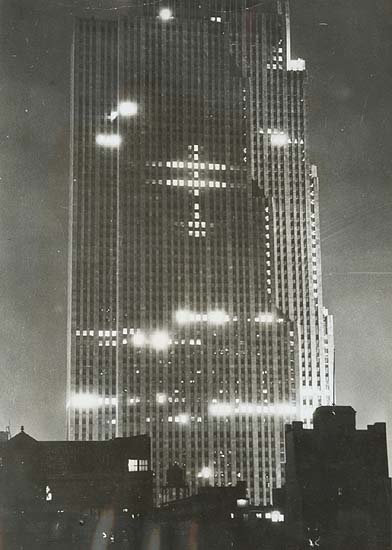

highlight of the complex is the General Electric Building, formerly the

RCA (Radio Corporation of America) Building. It is 850 feet of art deco

splendor spread out over 70-stories of shops, offices, broadcasting

studios, and more. In spite of its mammoth proportions, Rockefeller

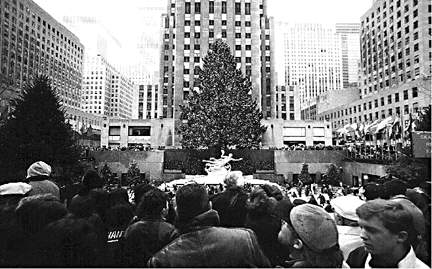

Center remains very pedestrian-friendly. It has a popular sunken garden

that is home to a café in the summer, and an ice skating rink in the

winter. Also in winter, the plaza's immense Christmas tree is

illuminated in an elaborate ceremony broadcast live across the country.

If Rockefeller plaza had a mascot, it would be Paul Manship's State of

Promethus. But it was not a Greek god that made this colossus possible.

It was America's first billionaire John D. Rockefeller, who in spite of

the Great Depression managed to build this huge office complex while

others predicted his failure. His fate was nearly sealed when the

Metropolitan Opera pulled out of the project. They were supposed to be

the linchpin in the operation. Now the problem facing Rockefeller's

architects was how to build enough office space to make the project work

economically. What they did is consolidate the entire 17 acre property

into a single superblock. Thirteen buildings would be short, allowing

light and air into the plaza and creating a human-scale experience. The

fourteenth building could be huge because it inherited the air rights of

its smaller neighbors allowing it to assume its 70-story height. There

are now 21 buildings in Rockefeller Center, housing such famous places

as Radio City Music Hall, the Rainbow Room, and the of NBC's shows like

"Today," and "Saturday Night Live." They are connected by a series of

underground tunnels which, themselves, support a variety of shops.

The original Rockefeller Center buildings

are:

- 1 Rockefeller Plaza (formerly the Time

and Life Building)

- 10 Rockefeller Plaza (formerly the

Eastern Airlines Building)

- 1270 Avenue of the Americas Building

(formerly the RKO Building)

- The Associated Press Building

- The British Empire Building

- Channel Gardens (so-called because it

lies between the British Empire Building and La Maison Francaise.)

- The International Building

- La Maison Francaise

- Palazzo d'Italia

- The Simon & Schuster Building (formerly

the U.S. Rubber Company Building)

- Rockefeller Center was originally a

collection of theaters and homes on land owned by Columbia University.

- There are 488 elevators in Rockefeller

Center.

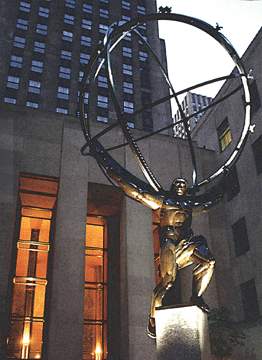

- In 1937, Rockefeller Plaza's statue of

Atlas by Lee Lowrie and Rene Chambellan created controversy because it

resembled Italian dictator Mussolini.

- At one time the Center featured a mural

by Diego Rivera. It was destroyed because it appeared to glorify Lenin

- 1999 - Radio City Music Hall underwent a

$70,000,000.00 renovation.

- June, 2001 - Another piece of oversized

public art has been installed at Rockefeller Center in New York. Last

summer a giant puppy made from flowers called the plaza home. This year

it's a huge spider big enough for pedestrians to walk under. The creator

of the 12-ton arachnid is Louise Bourgeois, an almost 90-year-old French

artist who titled the bronze spider "Mother."

- July, 2001 - A fire broke out at the top

of New York's Rockefeller Center. The blaze ignited in a construction

area next to the famous Rainbow Room restaurant. Diners were interrupted

during their meals and had to walk down to the ground floor from the

65th floor. No one was hurt.

Rockefeller Center is built on land formerly

owned by Columbia University since it was given a land grant from New

York State in 1814. A fashionable residential district in the 1860s,

this area lost much of its appeal by the 1920s due to the presence of

the 6th Avenue 'El.' Concerned with revitalizing the district around his

family home on 54th Street, John D. Rockefeller leased the site from

Columbia University in 1928. Rockefeller envisioned a new commercial and

civic center containing three office towers and an opera house grouped

around a plaza. The opera house was to be built for the Metropolitan

Opera, which had been looking for a new site since the early 1920's.

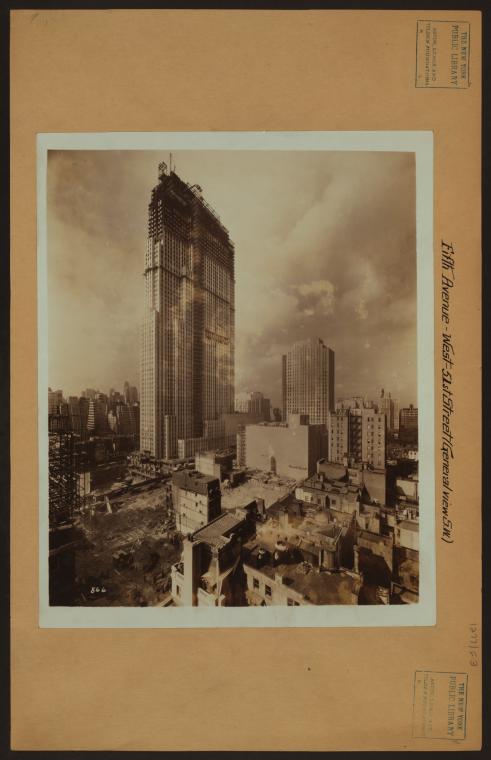

Plans were developed by an architectural

advisory board which was supervised by the pragmatic real estate and

management firm of John R. Todd. When the Opera withdrew from the

project, Rockefeller Center was transformed into a massive speculative

commercial and entertainment development, first called Radio City. The

architectural scheme was adapted to reflect the profit-driven nature of

the new complex.

A final scheme, designed by committee but

largely shaped by the aesthetic vision of Raymond Hood, was unveiled in

1931. Work progressed throughout the early years of the Depression,

supported by the Rockefeller's investment and aggressive marketing

strategies. Later renamed Rockefeller Center, this complex was the only

major private construction project underway in New York during the

Depression. The original 14 buildings of the Center were complete by

1939 and reached full occupancy by 1941. Partly inspired by the success

of Grand Central Station's "Terminal City," Rockefeller Center was

conceived as a "City within a City"-- the first real estate development

in the world to include offices, retail, entertainment, and restaurants

in one complex. While the overall plan has the hierarchy, symmetry and

axiality of a Beaux Arts design, the individual buildings have the

pronounced, streamlined verticality, set backs and massing

characteristic of Art Deco architecture.

In order to successfully market the project to potential tenants, the

project accommodated both business and leisure activities, facilitated

by a well thought out pedestrian and vehicular circulation system, and

complemented by extensive landscaping and public art programs. The

Channel Gardens slope gently from the modestly scaled 5th Avenue

frontage towards the center of the complex, encouraging pedestrians to

follow their path. Following the complex-wide theme of humanity's

progress towards new frontiers, Paul Manship's Prometheus [1934] and Lee

Lawrie and Rene Chmbellan's Atlas [1937] are among more than 100 works

by over 30 artists that grace the Center's plazas and buildings.

Amenities included a sunken plaza ringed with restaurants and shops, a

movie and vaudeville theater (Radio City Music Hall), as well as

observation decks and private dining rooms within the buildings. The

Center's appeal was enhanced by a subterranean shopping concourse that

linked the buildings, and provided direct access to mass transit (the

IND subway line).

In order to successfully market the project to potential tenants, the

project accommodated both business and leisure activities, facilitated

by a well thought out pedestrian and vehicular circulation system, and

complemented by extensive landscaping and public art programs. The

Channel Gardens slope gently from the modestly scaled 5th Avenue

frontage towards the center of the complex, encouraging pedestrians to

follow their path. Following the complex-wide theme of humanity's

progress towards new frontiers, Paul Manship's Prometheus [1934] and Lee

Lawrie and Rene Chmbellan's Atlas [1937] are among more than 100 works

by over 30 artists that grace the Center's plazas and buildings.

Amenities included a sunken plaza ringed with restaurants and shops, a

movie and vaudeville theater (Radio City Music Hall), as well as

observation decks and private dining rooms within the buildings. The

Center's appeal was enhanced by a subterranean shopping concourse that

linked the buildings, and provided direct access to mass transit (the

IND subway line).

A pioneering underground parking lot and an

off-street freight delivery system made doing business at Rockefeller

Center particularly convenient. Additionally, the complex was endowed

with many of the latest technical refinements including high speed

elevators, air conditioning and on-site steam and electricity plants.

With direct access to mass transit, an off-street delivery system,

numerous amenities and multi-level circulation, Rockefeller Center

anticipated the critical needs of today's urban centers, becoming a

prototype for malls, office parks and multi-use projects.

The world's finest Art Deco commercial complex and best private urban

renewal project, Rockefeller Center abounds in good design and

craftsmanship and its centerpiece is 30 Rockefeller Plaza, its tallest

structure that looms over the famous sunken plaza with its gilded statue

of Prometheus, shown above, by Paul Manship.

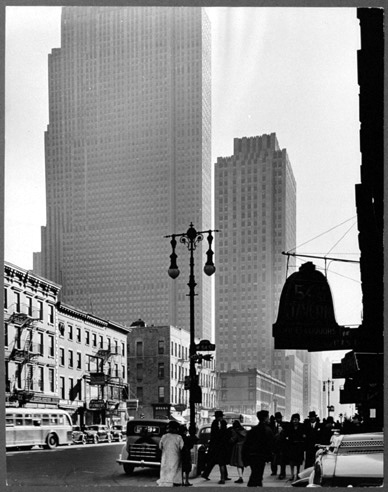

When it was built, midtown had not yet developed into the commercial real

estate juggernaut it has become. Most of the properties on the site were

occupied by low-rise rooming houses and brownstones.

The enormous project actually began when major patrons of the Metropolitan

Opera thought that its home in the Garment Center was no longer good

enough for its well-heeled patrons. A variety of schemes were developed

including plans to build a new opera house in the northern end of

Central Park, another to straddle Park Avenue at 96th Street, and banker

Otto Kahn purchased a large site on 57th Street between Eighth and Ninth

Avenues for which architect Joseph Urbann designed a gigantic circular

opera house with a giant office tower serving as its campanile.

The original plans, which became known as Metropolitan Square, did not

arouse sufficient interest from the opera's major patrons, however,

although John D. Rockefeller Jr., who lived on West 54th Street off

Fifth Avenue, had been approached to participate in its funding.

Rockefeller, who had already embarked on several major real estate

ventures such as the Riverside Church and International House in upper

Manhattan and Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, leased three blocks of

low-rise buildings from Columbia University between 48th and 51st

Streets, a property known as the university's “Upper Estate,” which had

been given to the university by the state which had received it as a

donation from Dr. David Hosack. Hosack, who had been the doctor who

attended Alexander Hamilton after his duel with Aaron Burr, had

developed the site as the Elgin Botanic Garden, name after his hometown

in Scotland.

One of the new plans for this midtown site called for the opera house to

be housed on the site on Fifth Avenue in a building with an elliptical

plan, but the opera bowed out of the proposal, leaving Rockefeller with

a major dilemma because the Depression boded poorly for real estate

development.

He bit the bullet and his plan, worked on by several major architectural

firms, but finally shaped into coherent form by Raymond Hood, provided

the city with a far more impressive and widely visible monument than an

opera house, 30 Rockefeller Center, a 70-story, 850-ft.-high slab

skyscraper whose form is subtlely modulated by stepped setbacks and

fully clad in gray Indiana limestone as are of the similarly styled

though smaller 13 other buildings in the original complex. The

consistent style was broken in the center's westward expansion in the

late 1950's across the Avenue of the Americas, which had an elevated

transit system when the complex opened and therefore was far less

desirable as a prime office location than Fifth Avenue.

From the street, the tower soars over the Channel Gardens between the

low-rise British Empire and La Maison Francaise buildings with a majesty

unrivalled in the city. Despite its bulk, the width of the tower's slab

shaft is proportionally small. The visual impact is greatly heightened

by the fact that the gardens slope gently downward toward the sunken

plaza and its neat and brilliantly colored, formal forest of national

flags. The flags not only add desperately needed color to the otherwise

drab gray limestone of the complex, but also motion, which is reinforced

in the winter when the plaza is converted to the world's most famous ice

rink.

The somber dignity of the center's facades is lightened by its art. Lee

Lawrie's “Wisdom, Light and Sound,” shown at the right, is a brilliantly

conceived entrance to 30 Rockefeller Plaza, combining an angled

indentation and sculpted glass blocks to dynamically express the

ceremony of entrance. Lawrie also designed the spectacular “Atlas”

statue, shown below, in the entrance court of the 38-story International

Building facing St. Patrick's Cathedral. The “Atlas” and the Prometheus”

statues are certainly the finest 20th Century public sculptures in the

city, if not the world: monumental and memorable artworks of great grace

and stupendous strength in dazzling and prominent settings.

Other important art at the center include Hildreth Meiere's large,

enameled metal rondels, “Spirits of Song, Drama and Dance,” on the 50th

Street facade of the Radio City Music Hall building; Isamu Noguchi's

stainless steel plaque, “News,” over the entrance to the Associated

Press Building; Attilia Piccirilli's glass block bas-relief, “Youth

Leading Industry,” over the Fifth Avenue entrance to the north wing of

the International Building at 636 Fifth Avenue; Giacomo Manzu's bronze

sculptures, “The Italian Immigrant” and “Italia,” at the entrance to the

Palazzo d'Italia in the south wing of the International Building at 626

Fifth Avenue, which was given to the center by Fiat of Italy and

replaced another Piccirilli glass bas-relief; and Carl Paul Jennewein's

bronze “Industries of the British Commonwealth” over the entrance to the

British Empire Building at 620 Fifth Avenue; and Alfred Janniot's gilded

bronze bas-relief, “The Friendship of France and the United States,”

over the entrance of La Maison Francaise at 610 Fifth Avenue.

The interiors were not to be barren, either. A list of competitors,

approved by Rockefeller, to do murals for the expansive lobby at 30

Rockefeller center included Matisse, Picasso, Frank Brangwyn, Jose Maria

Sert and Diego Rivera. Picasso, however, declined to even meet with some

of the project's architects to discuss the project and Matisse disdained

the notion of bustling people in an office building lobby being able to

be “in a quiet and reflective state of mind to appreciate or even see

the qualities” in his art.

Sert and Brangwyn agreed to do murals, entitled “Man's Intellectual

Mastery of the Material Universe,” and “Man's Conquest of the Material

World,” respectively for the elevator bank section of the lobby and

Rivera was commissioned for the lobby fronting the entrance.

Rivera, an avowed Communist, had been suggested for the competition by

John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s son, Nelson Rockefeller, whose mother, Abby

Aldrich Rockefeller, had commissioned Rivera previously to paint

portraits of her grandchildren. Rivera's mural, “Man at the Crossroads

Looking with Uncertainty but with Hope and High Vision to the Choosing

of a Course Heading to a New and Better Future,” was decidedly Marxist

in content and when someone noticed that a laborer bore a marked

resemblance to Lenin a major controversy erupted. Rockefeller was so

angered that Diego was dismissed and several months later the mural was

destroyed before it was ever shown to the public and replaced by the

present mural, “Man's Conquests,” by Sert. Although the sepia color of

the murals, shown above and below, is rather drab, they are impressive

and interesting nonetheless.

The center would have later controversies over a proposal to erect an

office tower over Radio City Music Hall, and the sale of much of the

ownership of the center to the Japanese, but nothing was as publicly

scandalous as the Rivera episode.

What was worse, however, was the center's decision in 1986 to close its

observatory atop 30 Rockefeller Center to provide more space for its

Rainbow Room and Rainbow Grill restaurant/lounge complex. The

multi-level observatory was the best in the city. Most architecture

critics were too busy raving about the refurbished Rainbow Room to

notice the loss. Patrons of the restaurants have views but they are

constrained and in no way comparable to the unrestricted vistas that the

observatory offered.

In an article in the November 11, 2003 edition of The New York Post, Steve

Cuozzo reported that "Rob Speyer, head of New York operations for

Tishman Speyer, which owns Rockefeller Center with Chicago's Crown

family," said the observatory will reopen in 2005 under a new plan that

calls for an entrance on West 50th Street that will lead to a mezzanine

where elevators will ascend to the 67th floor and its "fantastic

16-foot, floor-to-ceiling windows." The article did not indicate whether

the new public access will be allowed to the observatory's great outdoor

terraces and rooftop. The new plan is subject to approval by the city's

Landmarks Preservation Commission.

The center survives, of course, but much of its success had less to do

with its art program than with its urban design, its location as the

city's prime office market shifted uptown after World War II and with

its maintenance program, widely regarded as the best in the real estate

industry.

Interestingly, the sunken plaza was planned primarily to lure customers

down to the center's extensive underground concourses. Two large

restaurants flank its north and south sides and the sunken plaza is used

as an outdoor cafe when the skating rink is closed. The concourses,

which are also tied in to the subway system, never became prime

retail spaces, but are relatively attractive.

The Channel Gardens promenade, shown at the left, from Fifth Avenue down

to the sunken plaza constitute probably the city's finest public space

despite its relatively small size. Wonderful, very animated

fountainheads, sculpted by René Chambellan, who also was a major

designer for the Chanin Building on West 42nd Street, another Art Deco

masterpiece, are surrounded by benches and lush landscaping that is

changed seasonally. The flagstone promenade is lined with consistent

retail frontages and the spatial relationships are cozy despite the

vertiginous 30 Rockefeller Center tower. At Christmas time, of course,

the center's enormous lighted Christmas Tree, placed above the

fire-carrying Prometheus on Rockefeller Plaza, the three-block-long

private, north-south street that the center created, makes the

promenade/sunken plaza the world's most spectacular and popular hearth.

Taking a cue from the ring of flags around the sunken plaza, the center

installed fixed banners on all the lampposts around its properties on

both sides of the Avenue of the Americas. The banners definitely enliven

the streetscape and are occasionally changed, but sadly their design has

not always been inspired and free-flying flags would have been more

attractive, although obviously more expensive to maintain.

When GE decided to replace the large red RCA sign on the north and south

sides near the top of 30 Rockefeller Center with its own red GE sign, it

miffed some traditionalists who had for decades referred to 30

Rockefeller Plaza as the RCA Building. Amusingly, RCA was originally the

lead tenant in the tall, but slender Art Deco tower at 570 Lexington

Avenue that has served as the campanile for St. Bartholomew's Episcopal

Church on Park Avenue between 50th and 51st Streets. When RCA was lured

to Rockefeller Center, its building became the GE building. That

building recently was donated to Columbia University after GE put its

sign up at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, bringing a historical cycle

full-circle. The GE sign is no improvement over the RCA sign. There is

nothing wrong with placing a well-designed logo atop a building, but

these Art Deco-style thin font signs simply were and are intrusive,

tasteless and inappropriate. One can excuse the somewhat similar Radio

City Music Hall sign because it is a marquee and because it's not as

highly visible. When you've got the goods, as Rockefeller Center does,

you don't have to flaunt it.

The 5,960-seat Radio City Music Hall was one of two theaters originally

built at the center. The other, the 3,509-seat RKO Roxy was later called

the Center Theater, but was razed in 1954 for the new U.S. Rubber

Company Building in the center, which is now named the Simon & Schuster

Building. Roxy was the nickname of Samuel Lionel Rothafel who had built

the very large and famous Roxy movie theater, then the world's largest,

in 1927 on 50th Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues. The Roxy,

which featured the Roxyettes chorus line that set the precedent for the

Rockettes at Radio City Music Hall, was subsequently razed as have been

most of the city's greatest movie palaces, a preservation horror story

that in its aggregate was even worse than the loss of the former

Pennsylvania Railroad Station.

Radio City Music Hall continues to be one of the city's great tourist

magnets, but is more impressive for its scale than its decor, which was

coordinated by designer Donald Deskey. The large mural, entitled “Quest

for the Fountain of Eternal Youth,” over the grand lobby staircase is by

Ezra Winter. Yasuo Kuniyoshi decorated the women's room and Stuart Davis

the men's room, the latter mural entitled “Men Without Women.” Louis

Bouche's murals of American scenes against a black background in the

downstairs lounge was designed to encourage patrons to be quiet. Paul

Manship designed the bas reliefs on the orchestra doors. Shortly before

the theater opened, Roxy removed three statues of naked women by William

Zorach, Given Lux and Robert Laurent because he thought they might be

controversial. The art program for the theater was ambitious at least in

concept if not execution, but it is the theater itself that is the most

impressive achievement. Its enormous semi-circular proscenium arch is

banded with colored lights behind each band to permit the theater's

“color orchestrator” to “paint” the sunrise that the stage abstractly

looks like. With three very deep, but relatively shallow mezzanines, the

auditorium lessens the vastness of its space by extended its stage along

its sides.

Real estate holdouts and difficult economic times prevented the center

from achieving a more symmetrical unity. The south end of Rockefeller

Plaza sorely needs to be tied into the center and its northward

expansion was blocked by holdouts. The two low-rise bases on Fifth

Avenue of the International Building mirror the British Empire and La

Maison Française buildings on the block to the south creating a superbly

consistent and rhythmic modulation that ideally could have been

extended.

Overall, this pinstripe enclave is rather conservative and somber, yet its

glories far outweigh its imperfections, especially given the historic

context of the Depression when it was built. Its wonderful statue of

Atlas, by Lee Lawrie, shown at the right, not only is very impressive

but it also provides much needed space to appreciate the glories across

Fifth Avenue of St. Patrick's Roman Catholic Cathedral.

In the mid-90’s, the Japanese owners realized that they had paid too much

for their interest in the center and a battle ensued over its mortgage

with David Rockefeller, then the patriarch of the family, whose younger

generation had forced the sale to get more money, eventually regaining

control.

The dignified, homogeneous character of the huge center was severely

diminished by its westward expansion across the Avenue of the Americas

and the generally inferior architectural quality of that expansion. A

new expansion planned to extend to Seventh Avenue was announced at the

beginning of the 90’s, but was stymied for a few years by the city’s

real estate depresssion. It promises a return to quality.

In 1997, the center was acquired by an investment group headed by Tishman

Speyer Properties that launched a major program to upgrade its retail

spaces. It lured Christie's, the famous auction house, from Park Avenue,

but in 1998 its proposal to alter some of the center's retail frontage

by enlarging store windows incurred the justified wrath of many

preservationists who felt such changes were not only unnecessary but a

serious encroachment on the aesthetic integrity of the world's greatest

Art Deco urban complex. It proceeded with a major renovation that

included the temporary removal from the sunken plaza of the Prometheus

statue in early 1999 and placement on the sidewalk in front of the

entrance to 30 Rockefeller Plaza and the opening of Christie's at 20

Rockefeller Plaza in late April, 1999, with a new and large, colorful

abstract mural by Sol Lewitt in the lobby. The concourse spaces around

the sunken plaza were also handsomely renovated.

|