|

New York

Architecture Images-Upper East Side Central Synagogue |

||||||||

|

architect |

Henry Fernbach , restoration after 1998 fire Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates | ||||||||

|

location |

652 Lexington Avenue, 123 East 55th Street New York, NY 10022-3566 | ||||||||

|

date |

1872 | ||||||||

|

style |

Moorish Revival | ||||||||

|

construction |

polychrome brick with stone trim, internal cast iron frame. Basilical plan. | ||||||||

|

type |

Synagogue | ||||||||

|

images |

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

notes |

This

polychoromatic masonry building is the oldest synagogue in continuous use in

New York City. It was executed in an eclectic, rough-hewn Moorish style

popular for synagogues of the late 1800s.

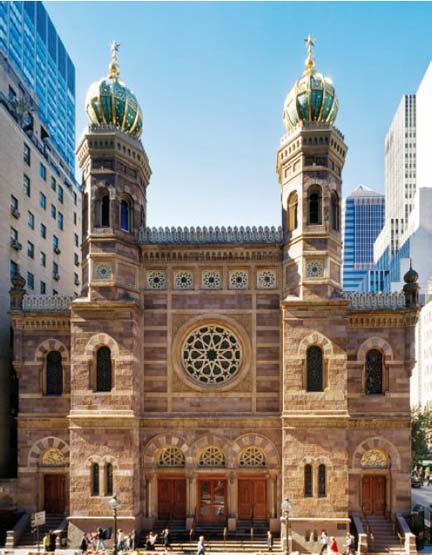

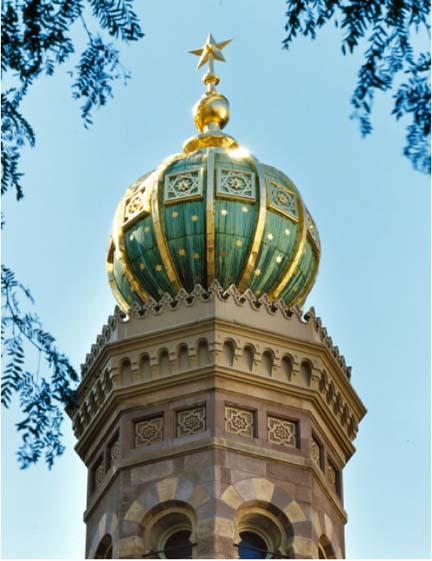

Central Synagogue at the corner of Lexington and 55th is the oldest synagogue in continual usage in New York City. Designed by Henry Fernbach of Germany, the design is loosely called "Moorish-Islamic Revival". The synagogue was built by Congregation Ahawath Chesed, a German Reform congregation meeting under that name on Ludlow street from 1846. The Exterior: is dominated by two octagonal towers rising 122 feet. They are meant to be reminiscences of Solomon's Temple. The towers are topped onion-shaped, green copper domes. There is one large rose window accompanied by many smaller arched windows. The Interior: has beautifully stenciled designs of red, blue, and ochre. Cast iron columns separate the inside into three sections. There is also colorful plates published by the English designer and colorist, Owen Jones. References:

Amy Nyack |

||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

For more information about Central Synagogue

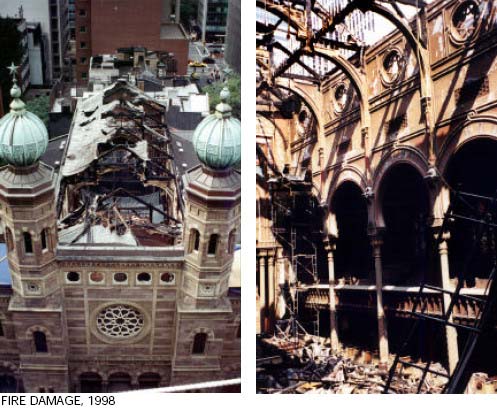

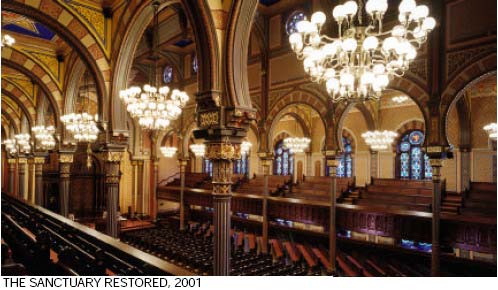

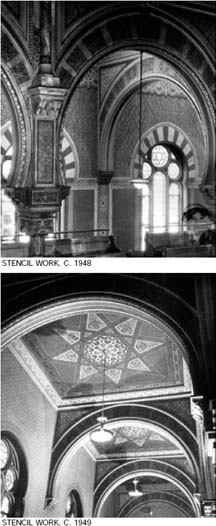

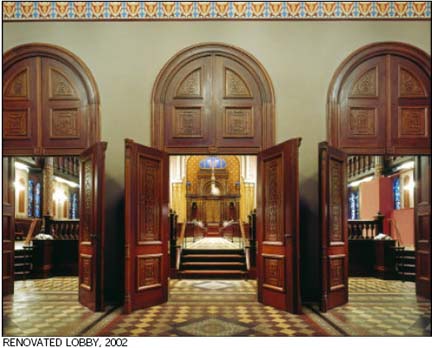

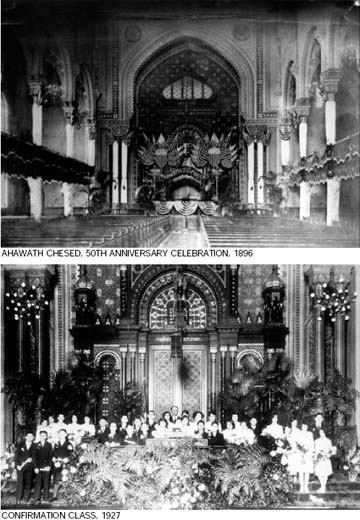

or for tours of the Sanctuary, please call 212-838-5122 or visit www.centralsynagogue.org . THE RESTORATION OF CENTRAL SYNAGOGUE Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates LLP (HHPA) is a leading architecture, planning, and interior design firm. Highly respected for some of the country's most notable architecture, HHPA has earned acclaim for its sensitive restoration of historic landmarks. The firm has received more than 100 national design awards including the AIA Architectural Firm of the Year Award, the highest honor that can be bestowed on an American architectural practice. The Restoration of Central Synagogue has won numerous awards to date, including a Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award from the New York Landmarks Conservancy. Introduction by Peter J. Rubinstein Senior Rabbi Central Synagogue Text by Hugh Hardy, FAIA Architect, Central Synagogue Restoration Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates LLP Opening 1872 Fire 1886 Fire 1998 Restoration 1998-2001 INTRODUCTION On behalf of the 1,700 families that comprise the membership of Central Synagogue, I welcome you to our home. Our congregation has served the Jewish community of New York City for more than 160 years and has occupied a unique place in our city since its formation. Central Synagogue had simple beginnings on Manhattan's Lower East Side when our parent congregations, Shaar Hashomayim and Ahawath Chesed, were founded in 1839 and 1846 respectively. By 1870, the membership of Ahawath Chesed prospered, grew and moved uptown. With amazing courage and vision, the 140 families of Ahawath Chesed commissioned Henry Fernbach, New York's first prominent Jewish architect, to design its synagogue, which seated more than 1,400 individuals. At its dedication in 1872, Rabbi Adolph Heubsch described the building as "a house of worship in evidence of the high degree of development only possible under a condition of freedom." In 1898 Shaar Hashomayim merged with Ahawath Chesed and became known as Central Synagogue in 1915. Though tempted to continue its move northward, in 1913 the Board of Trustees decided to stay on our present site, a decision for which we are grateful. Central Synagogue, designated a New York City Landmark in 1966 and a National Historic Landmark in 1975, is the oldest synagogue in continuous use in New York City and one of the leading Reform congregations in the country. However, our history includes devastation as well as celebration. On August 28, 1998, just as the congregation was preparing for Sabbath worship, a fire was accidentally ignited as workers were concluding a three-year renovation of the building. We are grateful that there were no serious injuries, but our synagogue was devastated. Thousands gathered and mourned the loss of our sanctuary. The roof and its supports were destroyed and several support beams fell, penetrating the sanctuary floor. The choir loft and organ were completely destroyed. Our prayer books also were severely damaged and, as we mourned, we buried them the following week in our cemetery. Removing the single step that raised the pews from the floor allowed reconfiguration of the bema. The reading table can be placed in two positions, either elevated on the bema or lowered to a sliding platform that extends toward the sanctuary, enabling clergy to be closer to the congregation. Greater flexibility of the first 13 rows is achieved by making these pews movable, so that more intimate services can be accommodated. The ark, which miraculously survived the fire, is a stalwart structure whose original finishes have been retained, giving authority and power to the whole. Music is an important part of the worship experience at Central Synagogue. The organ loft at the rear of the sanctuary containing the original 1926 organ was completely destroyed by fire. With installation of two linked organs and two audio systems, the synagogue now accommodates a wide range of musical forms. The organ loft houses the Gabe M. Wiener Memorial Organ, a world-class, electropneumatic organ for special services and concerts. Near the bema, a liturgical organ accompanies the cantor and choir and supports congregational singing. Both organs have access to 74 ranks and 4,345 pipes, including two unique stops: a Klezmer Clarinette and a Trompette Shofar. Designed by Casavant Freres of Quebec, the walnut and ash casework is an extension of the Moorish motifs found throughout the sanctuary. Placement of the organ pipes highlights the instruments' beauty without dominating the surrounding architecture. The circular pattern of the larger organ’s pipes frames views of the spectacular rose window. Although orchestrated by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates, the reconstruction and restoration of Central Synagogue involved many crafts and skills. DPK&A Architects provided analysis and documentation of the original plasterwork and stencil patterns, and made invaluable computer drawings and specifications. Professionals relied upon the original records, architectural drawings, descriptions, and photographs preserved in the Central Synagogue Archives. General contractor F. J. Sciame Construction coordinated the work of 70 trades and thousands of workers. Fisher Marantz Stone, Inc., designed the lighting throughout the building. A complete list of subcontractors, craftsmen, and engineers is available upon request. Miraculously, the ark was spared because it was under a separate roof. The Ner Tamid (Eternal Light) remained in place as did the mezuzah on the center door where it remained throughout the reconstruction. Most of our ritual objects, including the Torah scrolls, had been previously removed from the building because of the prior renovation. Fortunately, we were able to rescue our Holocaust Torah scroll, which had been dedicated in memory of Jews who perished in the Holocaust. We are grateful to the New York City Fire Department, especially the 8th Battalion, who saved the skeleton of our building, the exterior walls, all the windows on the main and gallery floors, and the rose window on the east wall over the choir loft. Although shocked and heartbroken, our congregation was determined to rebuild and restore our beloved sanctuary. Inspired by the history and traditions of our people, Central's congregation understood that we would need to wander, with the vibrant vision of someday returning to our home. So we did, carrying our Torah scrolls and accepting the warm hospitality of neighboring houses of worship and the National Guard Armory on Park Avenue and 66th Street. From the very beginning, former Mayor Giuliani, Governor Pataki, Cardinal O'Connor and then Cardinal Egan of the Archdiocese of New York, local clergy, and Jewish community leaders stood by us. We also received support from religious and community leaders from around the world and were visited by many, including the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Prime Minister of Israel. We are grateful to our congregants and friends whose contributions and expressions of support gave us the strength and resources to rebuild our beloved sanctuary. We also thank an exceptional group of professionals who made our vision a reality. On September 9, 2001, the newly restored Central Synagogue was reconsecrated. Now we have returned home. Our sanctuary represents a bridge between past and future. Though replicating much of the original 1870 plan, the restoration was designed to be responsive to contemporary Jewish life and religious practice. STAINED GLASS The sanctuary features 12 two-story, stained-glass windows crowned by clerestory roundels on the side walls, and an ornate rose window at the east end. The fire destroyed nearly everything at the clerestory level and above, including some of the last of the synagogue's original stained glass. However, enough historic glass was salvaged to reconstruct one window, which was dedicated to the firemen who saved so much of the building. The remainder was replaced with new glass that conforms to the original design. Three six-square-foot, stained-glass laylights, covered over for decades, were revealed during restoration. As originally intended, the ark is now bathed in colored light. STENCIL WORK Perhaps the most salient element of the synagogue's interior is the stencil work that covers the walls with highly patterned, colorful designs. Although this work has always been a feature of the sanctuary, its composition before the recent fire was more subdued than the original because of a repainting conducted in 1949 under the direction of Ely Jacques Kahn. The present restoration is a return to the exuberance of the historic scheme, with elaborate floral and latticework patterns announced in 69 colors including shades of green, terra cotta, slate, cream, peach, and red. Basic geometries of the patterns are highlighted by a gloss finish, and paint is deliberately applied in a loose, free manner to reinforce the handmade character. The seating arrangement was reconfigured, flexibility of pew and pulpit arrangements was integrated, audio and lighting elements were enhanced, and the soul of the congregation was figuratively and literally incorporated into every aspect of the restoration. (Members painted the stencils on the forward southern wall.) Our community is strong. Our spirits sing. Our visions for the future are as great as those of our founders. We are dedicated to the ongoing life and tradition of Judaism and the Jewish people. All of us at Central Synagogue are pleased and proud to welcome you to our sanctuary and to our worship services. Rabbi Peter J. Rubinstein HISTORY Of all the buildings constructed in New York in the late-19th century, none conveys greater optimism about the future of America than Central Synagogue. Built at a time of great expansion, 1870 through 1872, it was consecrated before the financial panic of 1873 and completion of the American Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Built by fewer than 150 families, it was designed to seat more than 1,000 congregants, and is one of a handful of surviving landmarks from that era. CONTINUITY Although not a large building by today’s standards, Central Synagogue has always graced the corner of Lexington Avenue and Fifty-fifth Street with great authority. It is the oldest synagogue in continuous use in New York City, and proudly proclaims its presence in what was originally a residential neighborhood lined with threestory row houses. Built before Lexington Avenue was widened and the subway was constructed below the street, it has stood resolute as the neighborhood was transformed into a vital part of the Upper East Side business district. Even juxtaposed with new high-rise structures, it continues to be an exceptional part of the neighborhood. ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN Central Synagogue was designed by Henry Fernbach, often cited as the first Jewish architect in America. Its two domed towers, crenellated decorative stone exterior with three entrance portals, and two side-aisle entrances surmounted by a great rose window represent an interpretation of the Dohany Street Synagogue in Budapest. Although Central Synagogue is not a direct copy, Fernbach was clearly influenced by this considerably larger building. Central Synagogue’s facade, a symmetrical composition of two sentinel towers topped by gilded onion domes, horizontal bands of stone in contrasting tones, and dramatic Moorish stone arches in alternating colors, identifies these walls as belonging to a singular place. By seizing upon Moorish precedent, Fernbach gave New York a synagogue whose exterior form and detail were—and still are—in sharp contrast to most other religious structures in the city. It remains a distinctive presence next to surrounding buildings. RECONSTRUCTION When the roof collapsed, it took with it a considerable amount of plasterwork and wood detail. However, the true culprit was water, which weakened the plasterwork and required replacement of all ornamental detail and surfaces, even those surrounding the ark. Therefore, with the exception of the stained glass, balcony fasciae, and the ark, every surface in the sanctuary has been restored. Even the ark, which miraculously survived the fire, had to be completely cleaned, refinished, and partly repainted and regilded. PLASTERWORK The new plasterwork was created from molds of the original designs, documented by DPK&A. These include extensive panel moldings, capitals, brackets, and intricate tracery found in the roof trusses over the bema and organ loft. Ornamentation and moldings that survived the fire were demolished, but not before they had been drawn in detail to illustrate connections, appearance, and sequence for installation of the new decorative plasterwork. All ornamental detail was cast in sections and applied on site, matching original patterns defined by DPK&A’s computer drawings. Wall surfaces were finished with a skim coat of sand plaster to give a modulated effect that simulates hand-applied plaster. SEATING AND FLOOR TILE In the original seating configuration, people in the side pews faced straight ahead, parallel to the west wall, not angled toward the bema. This orientation has been changed so that the side pews are shifted at forty-five degrees, providing a greater sense of community. All pews were originally raised by one step to accommodate heating elements, and this step has been removed. The pews are new and match the original in walnut and ash. Reinforcing their placement are 4,000 square feet of encaustic and quarry-tile flooring in both the lobby and the sanctuary. More than 40,000 tiles in a wide range of colors, patterns, and sizes make up the design. Many original tiles were salvaged and cleaned, but 30,000 new ones were fabricated by the successor of the original manufacturer of the 1872 tiles in England. Old and new tiles have been integrated in a pattern so that it is difficult to tell the difference between them. FIRE DAMAGE, 1998 THE 1998 FIRE The accidental fire of 1998 started at roof level, and consumed the roof and most of its wooden truss supports. The resulting collapse severely damaged the historic interior. Most destructive to the plasterwork was inundation by water. It destabilized the bond between plaster and lath, requiring the removal of 85 percent of all decorative surfaces. This devastation allowed restoration of the paint scheme done after an 1886 fire. This largely followed the patterns established in 1872, which restoration consultant, DPK&A, was able to accurately document through historic photographs and paint analysis conducted on site. This is a far more robust scheme than the one Ely Jacques Kahn created for a repainting in 1949, which remained until the 1998 fire. The new interior seems comfortably familiar to congregants, but restoration enabled us to create a space that is even more resplendent than it was before. THE SANCTUARY RESTORED, 2001 ORGANIZATION Traditional in plan, the sanctuary features a tall central nave and two side aisles, with galleries and an organ loft above. The space is subdivided into six bays by ten slender cast-iron columns in high relief. The bema is crowned by the original ark, which is richly carved and inlaid with fretwork patterns highlighted in gold topped with onion domes finished in celestial blue and gold stars. A focal point of the ark’s central dome is a gilded Star of David. SANCTUARY The sanctuary celebrates worship with a dramatic deep blue ceiling, stencil work in 69 colors, molded-plaster patterns, and carved wood in walnut and ash. The entire composition is highlighted in gold and dematerialized by patterns of colored light filtered through stainedglass windows and rediscovered skylights over the ark. At night, the space is lit by twelve chandeliers, whose design was interpreted from photographs of the originals and from documentation of those designed for the Dohany Street Synagogue. In addition, several concealed sources of light were required to meet current standards. DISCOVERY Passage into the restored interior is a ritual of discovery and renewal, a way to focus attention on the permanence of community in the constant change of contemporary society. It is clear upon entering that one has left everyday experience behind and joined in exalted awareness of an extraordinary place. The power of this remarkable space is revealed when one enters the sanctuary by stepping up from a newly configured lobby. For those who come to worship, it is a glorious return home. RENOVATED LOBBY, 2002 REDESIGNED LOBBY ENTRANCE In order to bring light into the lower level, which was originally used for classrooms, Fernbach raised the sanctuary approximately seven feet above street level. Following the construction of the subway and the resulting widening of Lexington Avenue in 1912, a steep, seemingly vertical flight of steps was constructed to give access to the entrance. The small entrance lobby was then bisected by two additional steps, making for awkward movement into and out of the synagogue. The new design changes this sequence by lowering the lobby so that it can be accessed by exterior stairs with a gentler rise. Inside, two steps were removed and the existing portals were lowered to meet the new floor. Four steps were then added just inside the sanctuary doors, creating a new and dramatic entrance into this sacred space. Although the new work is a change from the original configuration, it has been seamlessly incorporated into the old. |

|||||||||

|

Sanctuary By Jennifer Acker Flames continued to surge but, across the street, prayer began again. Crowds of onlookers gathered around the burning temple, but the congregants didn't emerge to join them until after they prayed. "What Jews have been able to do throughout their history is to continue to pray, even in the midst of the darkest nights," says Rabbi Peter Rubinstein '64 of Manhattan's Central Synagogue. So on August 28, 1998, while the New York City Fire Department rushed to quell the flames, Rubinstein directed his congregation to "Go and have a service." It was Shabbat, the holy close to the Jewish week. Afterwards, the congregation formed a circle and was joined by then Mayor Guiliani and Cardinal O'Connor, archbishop of New York, as well as firefighters and others. They prayed for a future in which they could be together again in a safe and spiritual place of worship. Rubinstein told the gathering, "We will wander for a while, but there will be a day when we'll open those doors and enter with the Torah scrolls again." Three years later, Central Synagogue had been restored to its Moorish splendor—and modernized in subtle, crucial ways—under Rubinstein's guidance. A group similar to those holding hands in 1998 gathered to celebrate the synagogue's reopening, standing on the building's steps in bustling midtown Manhattan. People smiled, cheered; photojournalists flashed their bulbs as Guiliani spoke of the strong "faith of the Jewish people" and how he would remember being at this site and with these same people for both the temple's destruction and its consecration. It was September 9, 2001. Standing on the opposite street corner, on the east side of 55th and Lexington, one feels that the city has grown up around Central Synagogue. Its landmark gold domes are striking, but difficult to see given the skyscrapers that encircle them. Sharing sandwiches and cigarettes, construction workers take their lunch break on the temple steps. A few stairs lead up to the three keyhole-shaped entrances; the lobby is warm and bright with honey-colored woodwork and smooth tile floors. The viewer passes through another set of doorways and beholds the magnificent interior: rows of dark, wooden pews set on cream, brick, and olive tiles; ornate stencils in warm orange and sienna tones decorate side walls that rise to stained glass windows; two rows of elegant chandeliers lead the eye to the ark where a simple raised platform, or bimah, with a lectern is backed by a cobalt dome. A dusk blue ceiling sparkles with gold stars. Congregant Sam Charap '02 describes the pre-restoration synagogue he grew up in as "astoundingly beautiful—breathtaking inside and out." With its intricate design the building is Charap's favorite in the world. At first glance, he says, the "new" synagogue looks much the same as the one before it, only better. News of the 1998 fire—started by the blowtorch of a construction company installing an air-conditioning system—made the front page of The New York Times. Even to Charap, distanced by college activities and geography from his Manhattan congregation, "It felt like a devastating blow." Not only was the building a place of beauty he had fallen in love with over the years, but his synagogue was a spiritual place of worship—an atmosphere created in no small part by his Amherst-educated rabbi, Peter Rubinstein. Rubinstein has led Central Synagogue, his third congregation, as its senior rabbi since 1991. While at Amherst, however, he was not part of a Jewish community, and he was barely acquainted with the college rabbi, jointly appointed to Smith College. The study of religion was attractive, but it was Christian theology that fascinated Rubinstein. Religion Prof. John Pemberton, now retired, had "an extraordinary, singular impact on my life," the rabbi says, because he introduced him, a medical school-bound English major, to thinking about religion systematically, in keeping with the student's background at the Bronx High School of Science. After graduation Rubinstein said to his brother, then in rabbinical school, "I'm clear on what Christians think, but I'm not certain about what Jews think." Rubinstein deferred the M.D./Ph.D. program he'd been accepted to for a year of study at Hebrew Union College—then never left. Christian theology, as well as serious interreligious dialogue, remain a part of the adult rabbi's life. He chairs the board of directors of the Auburn Theological Seminary and has the distinction of being the only member with a Master of Hebrew Letters. David Moore '79 was married in the majestic Central Synagogue, and he began taking his children to Rubinstein's services when they were still toddlers. Moore remembers his rabbi "would call them up onto the bimah to stand with him. It got them more comfortable so that they liked being there. What greater joy for a parent than to have your children enjoy going to synagogue?" Rubinstein's encouraging attitude had a ripple effect within the congregation, as they witnessed the warmth he extended to children, telling them they mattered and should be included. When the temple burned, it was up to the senior rabbi to take this congregation he had nurtured and lead them into a new era. They faced enormous decisions regarding architecture, history, community and, of course, religion. Rubinstein needed to consult a congregation of nearly 4,000 members, some of whom are ranking members of the political and social elite—Public Advocate and recent mayoral candidate Mark Green and Estee Lauder heir Ronald Lauder. Where did he begin? "The very first issue we had to confront was: Should we rebuild?" Rubenstein says. "Our building was completely destroyed except for its external walls. The roof had caved in, and everything in the interior [except the ark] had been destroyed by fire or water. So, what was our commitment to history? To our location—the heart of the commercial section of New York?" Once the congregation resolved to rebuild, Rubinstein asked the next question: "Do we rebuild to what we had?" Their synagogue was the city's oldest still in use. Built in 1872 to seat 2,000 attendants, the sanctuary was designed by Henry Fernbach, considered the first practicing Jewish architect in the United States, for a congregation founded by Jews from Bohemia. "The building we had in 1998 was in many ways different from what was there in 1870. Elements had been taken away, stencils had been simplified," says Rubinstein, who has studied the synagogue's archival photographs and plans. "So did we go back to 1870, or 1998, or a time in 1940?" The answer was one of integration. Architect Hugh Hardy—who also renovated Radio City Music Hall—was pleased to strip away some of the 20th-century add-ons and reveal Fernbach's original intentions. Rubinstein, the architects and the congregation now had a structural concept for the restoration. But what about the spiritual vision? Surely today's congregation holds vastly different ideas about Judaism and religion than their forebears did more than a century ago, when the world was slower, more segregated, more authoritarian. Rubinstein began to consider, "What have we learned about worship that would lead us to evolve that building?" Members' renovation suggestions were largely practical—better sound, better light, easier to enter—but they pointed, importantly, to overall preferences for the feeling of the synagogue: welcoming or off-putting, safe and intelligible or cold and remote. Worship has undergone dramatic changes just in Rubinstein's lifetime. "Those of us who were in college in the '60s always see Vietnam as a watershed," he explains. "In certain ways [the war] did shape the idea of what authority was. In many ways the clergy and the pulpit represent authority, usually signaled architecturally as well as liturgically. That began to evolve, and I think the pace quickened in the '80s and '90s when people were gaining everything they ever thought they wanted and began to ask: ‘Is this all there is?'" Rubinstein looks through his square glasses thoughtfully, but as if he has considered and discussed these issues many times before. "Once you ask that question, one's spiritual being comes to the fore. People did not want to act as an audience to drama. Though there need to be elements of drama, that is not all we are. "Worship now needs greater accessibility to the front. It involves greater interfacing of all the elements of the service: music, worship, clergy, the congregation. It demands a greater sense of involvement and participation. And more than anything else, to build now demands that you know that you don't know, that worship and its needs change rapidly and radically." Despite the building's age and status as both a city and national historic landmark, the sanctuary has been equipped with invisible 21st-century technology such as visual and digital sound recording devices to Webcast services. Restoration planners also had to acknowledge the current population's extended longevity. The main lobby was sunk to eliminate two feet of exterior stairs that were frightening to older people. A first-floor bathroom is unisex and spacious enough for physically limited seniors with opposite-sex caregivers. "I realized this was the case of my parents," the rabbi says. On a tour through the building, Rubinstein, small-framed with graying hair and dressed in a blue suit, points out that the front 12 of the 148 new pews—"all equally uncomfortable as the old ones"—are moveable, to create greater intimacy during small services. Similarly, the bimah functions like a trundle bed, pulling out closer to the congregation. Rubinstein purposefully puts his left foot on a spot at the end of a row, and his right a short distance apart and says, "You can straddle 130 years." The tiles under his right foot are brighter than the ones to the left, but they show a precise color match. Both sets—from 1872, and post-restoration—were made by the same manufacturer in England. Columns support the balcony and the seven trusses that form the basic structure of the synagogue. One collapsed during the fire, but the other six were saved. The firefighters knew these remaining trusses couldn't fall, and chose their means of rescue carefully; they poked a six-inch hole in the dominant, rose-shaped stained glass window on the street side of the synagogue, but quickly realized that position was not advantageous and saved the window. "They treated the sanctuary with such dignity and respect," the rabbi said. Several days after the fire the department returned to study the structure and create plans for rescuing comparable buildings in the future. Rubinstein has framed pictures of these men on his office wall. The man in charge of the rescue was killed, along with many of his workmates, during the collapse of the World Trade Center. This congregation, however, was ahead of the city in fully appreciating the fire department and other civic workers, though they had a hope-filled, rather than tragic, occasion to commemorate. Before the September 9 consecration, Central Synagogue had dedicated the preserved rose window to their firefighters. Rubinstein not only implements structural changes that make the sanctuary and worship services inviting and accessible, he also develops programs that contain a vision of a collective future. Genuine warmth and embrace of community have come to be hallmarks of the rabbi's leadership style. In a decision that might strike other leaders as unusual, Rubinstein has committed himself to an often overlooked social group: teenagers. He loves them. Talking about them makes him laugh. He directs the Confirmation program, a ceremony of renewed faith occurring in 10th grade, two years after a Bar or Bat Miztvah. "Teenagers can be tough, okay. I remember," Rubinstein says from a couch in his book-lined office. "There is something so alive and challenging and vital during that period of time. It's an important time for people who are generally anti-authority, who are seeking and challenging," Rubinstein says. As their rabbi, he does something special for teens. "I take them seriously," he says. "I care about them. I promise them that I will be their rabbi until they find their own. Wherever they go they know this is their home and they can always come back." A synagogue is not just a building, a house, for those who are present. It is a community that must be flexible and embody a continuous spirit. Sam Charap was recently reminded of being a young teenager in Rubinstein's congregation. An envelope from Central Synagogue arrived in his campus mailbox this year. Inside was a letter that a 15-year-old Charap had been instructed to write to himself six years ago, describing how he felt about himself at the time, his relationship to Judaism. It was "remarkable," Charap says, "I was reminded of the place of Judaism in my life, what it still means to me." This effect is exactly what Rubinstein intends. "[Writing the letters] does two things," he says. "Number one, it demonstrates in the most dramatic way that we still care about them, that [these youth] still have a connection to this place. The second is that it provides a time mark. I ask them to write about themselves and their thoughts on where they'd like to be, to paint a picture of what's important now, the things they care about and remember." Six years later the recipients compare themselves to the young writers, noting whether they are where they thought they'd be and whether their goals have changed. During the three years of labor-intensive restoration, the rabbi held out a vision for his synagogue, much as he asked his teens to do for themselves. But Rubinstein's aspiration for Central Synagogue wasn't grounded in their future house of worship; rather, it was a life-affirming conception of who they were as a group, as Jewish people. For Jews, he says, are never "locked to a particular sacred space." David Moore adds, "In Judaism you can have a service in the woods; there's no religious significance to a synagogue as a building." The congregation did repeat the stories of the Bible; they wandered for several years. Small services were held in many different homes—Rubinstein says he would eat hors d'oeuvres at one table and appetizers at the next, until over several nights he had visited all 50 of the congregation's gathering places. "It was a wonderful time of journey," he says. Reminding people that their misfortune was not a tragedy—"A tragedy would be loss of life"—he emphasized continuity in the vacuum of a central space. Through this process a mental transition occurred: the community ceased to align itself with an awe-inspiring historical landmark and began to think of itself as something far greater. Rubinstein says, "Since then, it is much clearer that the sanctuary may be—how could I say this—it may be a projection of what we are, but it's not who we are. We are something much more profound and deeper than that place." Rubinstein would come to draw upon this depth of spirit more than he could foresee. On Sunday, September 9, Central Synagogue was exuberant—celebrating their homecoming and rebirth with media, with civic and political figures, with New York City as a whole. "We had about two days of consummate joy," the rabbi recalls. Then came the terrorist attacks and all the mayhem and destruction of September 11. Because of the hope and faith with which he carried his synagogue from the eve of the fire until the dawn of its renaissance, and because of his existing connections with the fire department, a network of religious leaders, and politicians Guiliani and Governor Pataki, Rubinstein played an important role in New York City's response. David Moore describes him as already "ascended," through his brilliant congregational rapport and leadership, when real tragedy struck. Rubinstein describes Guiliani's motivation in inviting him to Ground Zero for President Bush's emotional and photographic visit. The governor and the mayor "thought of [Central Synagogue] as a symbol for rebuilding. They introduced me to the President saying, ‘This is a congregation that lost its sanctuary and rebuilt. And this is exactly what we're going to do. They built out of the ashes.'" Bush's visit was on Friday, Shabbat. Moore remembers Rubinstein walking into services "with the dust from Ground Zero on his shoes." The sanctuary was packed. There were twice as many attendants as the usual 700. "Everyone was there to be comforted. We were all nervous." Rubinstein talked about his visit to the scene of the destruction, of his time with the president, and suddenly listeners felt, through their rabbi, a great connection to the city—that they, too, were involved in the communal mourning and the effort to understand. With the tremendous, desperate need for prayer and memorial services, Rubinstein's synagogue remained a focus. Just the following week was Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and Central Synagogue had a special guest. Upon the mayor's entrance, "the place erupts in a standing ovation," Moore remembers. "There wasn't a dry eye in the place." Guiliani had planned to attend even before September 11, and with his multitude of obligations that week, people expected he would stay only a short time. "I asked [Guiliani] if he wanted to speak—at this point he was the messiah—" Rubinstein says, "and he spoke beautifully. Then he sat through the service. I was very moved by that. He sat with me on the pulpit. Afterwards I told him how touched I was." The mayor responded, "I needed it for me." In the ensuing weeks and months, citizens continued to flock to Central Synagogue, members, non-members, even non-Jews. "Those who had been saved needed to talk," Rubinstein says. The rabbi talked and counseled, and talked and prayed, and prayed more. ----------------------------------------------------------------- There's a heroic story about Rubinstein rushing into the synagogue the night of the 1998 fire to save a historic Torah, one that had been rescued from the Nazis. He did run in, and though he wasn't the one to break the glass case with his elbow, as the newspapers reported, Rubinstein admits to pulling out the Torah and carrying it to safety, a feat that greatly upset the fire department. He shrugs, as if he is amused by the "myth," as he calls it. "Who knows if my life was in danger? I mean, there was fire and there was smoke, but I thought, ‘Rabbis are invulnerable.'" Then he sent the congregation to pray. |

|||||||||

|

Dohany Synagogue in Budapest

Henry Fernbach based his designd for the Central Synagogue on the Dohany Synagogue in Budapest. Some images:

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

The Great Synagogue in Dohány Street, Budapest

The Great Synagogue in Dohány Street, also known as the Dohány Synagogue, or the Tabac-Schul, the Yiddish translation of dohány (tobacco), after the Hungarian name of the street, is located in Belváros, the inner city of Pest, in the eastern section of Budapest. It was built between 1854-1859 by the Neolog Jewish community of Pest according to the plans of the Viennese architect Ludwig Foerster. The synagogue neighbors a major Budapest thoroughfare expressing the optimism and the newly elevated status of the Hungarian Jews in the mid years of the 19th century. It is a monumental, magnificent synagogue, with a capacity of 2,964 seats (1,492 for men and 1,472 in the women's galleries) making it one of the largest in the world. The building has a length of more than 53 meters while its width has 26.5 meters. The design of the Dohány Street synagogue, while basically in a Moorish style, also features a mixture of Byzantine, Romantic, and Gothic elements. The western facade boasts arched windows with stone-carved decorations and brickwork in the heraldic colors of the Budapest: blue, yellow and red. The western main entrance has a stained glass rose window above it. The gateway is flanked on both sides by two polygonal towers with long arched windows and crowned by copper domes with golden ornaments. The towers rise to a height of 43.6 meters each, their decoration features stone carvings of geometric forms and clocks with a diameter of 1.34 meters each. The facade is topped by the Tables of Covenant. The synagogue's interior, designed by F. Feszl, has wall surfaces adorned with colored and golden geometric shapes. The Holy Ark is located on the eastern wall, facing the nearby Bimah. The choir-gallery is situated above the Holy Ark, while the women's galleries, supported by steel ornamented poles, are located at the upper levels on both southern and northern sides of the synagogue. During the 1933 renovation works of the synagogue a mikveh was revealed under the Holy Ark. The 5,000 tube synagogue organ was built in 1859; Franz Liszt and C. Saint-Saens are probably the most famous musicians that played on this remarkable instrument. M. Friedman, A. Lazarus, Z. Quartin, and M. Abrahamsohn are among the distinguished cantors from the Great Synagogue in Dohány Street that gained world recognition. Theodore Herzl, whose house of birth was located in the vicinity of the synagogue, had his Bar Mitzvah celebrated in this synagogue. In 1944, the Dohány Street Synagogue was included first in a military district, then in an internment camp for the city Jews. Adolph Eichmann turned it in a concentration point from which the Nazis sent many of the Budapest Jews to their extermination. Over two thousand of those who died in the ghetto from hunger and cold are buried in the courtyard of the synagogue. The synagogue was also used as a shelter, and towards the end of World War 2, the building suffered some severe damage from aerial raids during the battle for the liberation of Budapest. After World War 2, the damaged structure became again a prayer house for the much-diminished Jewish community. Only in 1991, following the return to democracy in Hungary, the renovation works could start and were completed in 1996 when once again the building was restored to its former beauty. In 1991 a monument dedicated to the memory of the Hungarian Jews who perished in the Holocaust was installed in the rear courtyard of the synagogue, in a small park named for Raoul Wallenberg. The Holocaust memorial, the work of Imre Varga, resembles a weeping willow whose leaves bear inscriptions with the names of the victims and boasts the inscription Whose agony is greater than mine. 240 non-Jewish Hungarians "righteous among the nations", who saved Jews during the Holocaust, are inscribed on four large marble plaques. The memorial was made possible by the generous support of the New York based Emanuel Foundation for Hungarian Culture, with funds raised from private donors. The National Jewish Museum (Orszagos Zsido Vallasi es Torteneti Gyujtemeny) is located within the synagogue compound. Today the Great Synagogue in Dohány Street, for a long time one of the most renowned landmarks of Budapest, is serving as the main synagogue of the local Jewish community as well as a major tourist attraction.

|

|||||||||

|

links |

http://www.centralsynagogue.org/ |