|

New York Architecture Images-Upper East Side Temple Emanu-El |

|

|

architect |

Clarence Stein, Robert D. Kohn, and Charles Butler | |

|

location |

840 Fifth Ave. At East 65th. | |

|

date |

1927 | |

|

style |

Romanesque Revival | |

|

construction |

stone, structural steel frame | |

|

type |

Synagogue | |

|

|

Founded

1845; first Reform congregation in New York City; consolidated with

Temple Beth-El in 1927; present structure completed in 1929 and

dedicated in 1930; largest Jewish house of worship in the world;

Goldsmith Religious School Building dedicated in 1963 |

|

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

Congregation Emanu-El of the City of New York was the first Reform Jewish

congregation in New York City and, due to its size and prominence, has

served as a flagship congregation in the Reform branch of Judaism since

its founding in 1845. Its landmark building on Fifth Avenue is the

largest Jewish house of worship in the world. The congregation,

currently 3000 families strong, is led by Senior Rabbi Dr. David M.

Posner. Emanu-El means "God is with us" in Hebrew. Over 60 other Reform Jewish synagogues share this name from San Francisco, California to Dallas, Texas to Livingston, New Jersey and also in cities outside the US, such as Victoria, British Columbia and Buenos Aires, Argentina.. History The congregation was founded by 33 mainly German Jews who assembled for services in April 1845 in a rented hall near Grand and Clinton Streets in Manhattan's Lower East Side. The first services they held were highly traditional. The Temple (as it became known) moved several times as the congregation grew larger and wealthier. In October 1847, the congregation relocated to a former Methodist church at 56 Chrystie Street. Radical departures from Orthodox religious practice were soon introduced to Temple Emanu-El, setting striking precedents which proclaimed the principles of 'classical' Reform Judaism in America. In 1848, the German vernacular spoken by the congregants replaced the traditional liturgical language of Hebrew in prayer books. Instrumental music, formerly banished from synagogues, was first played during services in 1849, when an organ was installed. In 1853, the tradition of calling congregants for aliyot was abolished (but retained for bar mitzvah ceremonies), leaving the reading of the Torah exclusively to the presiding rabbi. Further changes were made in 1854 when Temple Emanu-El moved to 12th Street. Most controversially, mixed seating was adopted to further gender equality, allowing families to sit together, instead of segregating the sexes on opposite sides of a mechitza. After much heated debate, the congregation also resolved to observe Rosh Hashanah for only one day rather than the orthodox two. In 1857, after the death of Founding Rabbi Merzbacher, German speakers still formed a majority of the congregation and appointed another German Jew, Samuel Adler, to be his successor. In 1868, Emanu-El erected a new building for the first time, at 43rd Street and 5th Avenue after raising about $650,000. The congregation hired its first English speaking rabbi, Dr. Gustave Gottheil, in 1873, from Manchester, England. In 1888, Joseph Silverman became the first American born rabbi to officiate at the Temple. He was a member of the second class to graduate from Hebrew Union College. The 1870s and 1880s witnessed further departures from traditional ritual. Men could now pray without wearing kippot to cover their heads. Bar mitzvah ceremonies were no longer held. The Union Prayer book was adopted in 1895. Felix Adler, the founder of the Ethical Culture movement, came to New York as a child when his father, Samuel L. Adler, took over as the rabbi of Temple Emanu-El, an appointment that placed him among the most influential figures in Reform Judaism. Emanu-El merged with Temple Beth-El on April 11, 1927 and both are considered co-equal parents of the current Emanu-El. In 1929, the congregation moved to its present location at 65th Street and Fifth Avenue, where the Temple building was constructed to designs of Robert D. Kohn[2] on the former site of the John Jacob Astor mansion. The vast load-bearing masonry walls support the steel beams that carry its roof. The hall seats 2500, larger than St Patrick's Cathedral (AIA Guide) By the 1930s, Emanu-El began to absorb large numbers of Jews whose families had arrived in poverty from Eastern Europe and brought with them their Yiddish language and devoutly Orthodox religious heritage. In contrast, Emanu-El was dominated by affluent German-speaking Jews whose liberal approaches to Judaism originated in Western Europe, where civic emancipation had enticed Jews to discard many of their ethnoreligious customs and embrace the lifestyles of their neighbors. For the descendants of Eastern European immigrants, joining Temple Emanu-El often signified their upward mobility and progress in assimilating into American society. However, the intake of these new congregants also helped to put a brake on, if not force a limited retreat from, the 'rejectionist' attitude which 'classical' Reform had espoused towards traditional ritual. |

||

|

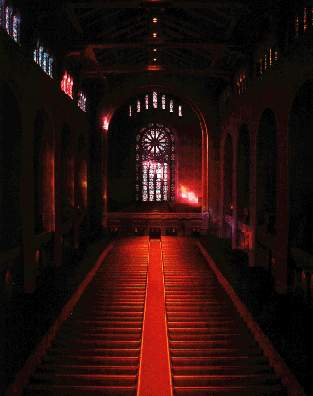

INTERIOR SANCTUARY Awe, majesty, soaring spirituality are feelings that are invoked when one first steps into the 2,500-seat Main Sanctuary. In the vastness of the space and the quiet dignity of the mood we feel the presence of God. The play of light refracted through the clerestory windows against the arched side walls are a luminous reminder that this sanctuary is expressive of God's spirit. The feeling of a large, unified enclosed space (77 feet wide, 147 feet long and 103 feet high) is engendered by the seeming absence of interior supporting pillars, made possible by the system of buttresses. Designed by the architects, Clarence Stein, Robert D. Kohn, and Charles Butler, they represent an early example of the advantages of a structural steel frame. Another innovation was Gustavino acoustical tile applied to the walls above the marble wainscoting, giving the Sanctuary remarkable acoustical qualities.

|

||

|

INTERIOR SANCTUARY ARK

The ark itself is depicted as an open Torah scroll. The usual pillars to left and right here become atzei hayim, the staves of the Torah scroll, and on the doors of the ark are the Tablets of the Law. The finials at the top of the columns have the look of elegant rimmonim, decorations for the finials of the staves. Hanging in front of the ark is the ner tamid (eternal light), symbolic of God's eternal presence.

|

||

|

WHEEL WINDOW

Turning back to the entrance we can see the lustrous radiance of the great wheel window of the facade, designed by Oliver Smith. Its pattern and style were conceived as echoes of ancient Jewish art. The twelve spokes of the wheel recall mosaic synagogue floors built in the Holy Land during the second to sixth centuries of the Common Era. In ancient maps, the world was depicted as a great circle with Jerusalem as its center. This window, with its suggestion of the cosmos, has as its center the six-pointed star variously called the Jewish Star, the Seal of Solomon or the Star of David. The numerical configurations resonate with themes of Jewish mysticism, twelve spokes for the Jewish tribes or months of the year, and eighteen segments in the surrounding arch for the Amida, the eighteen-part daily prayer.

|

||

|

BETH-EL CHAPEL

Moving northward through the lobby, we enter the Beth-El Chapel--named for the congregation that merged with Emanu-El in 1927. This chapel seats 350. Though smaller (50 feet wide, 84 feet long and 45 feet high) than the Main Sanctuary, it evokes a stately nobility that possesses its own intimate elegance. Its most striking feature is a profusion of columns that cascade forward and backward through the space. These arches, in conjunction with the two domes that echo their curves, yield to the chapel a distinctly Byzantine flavor. The ark doors are copies in steel of bronze ark doors at Temple Emanu-El on 43rd Street, a gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jacob Schiff in honor of the confirmation of their granddaughters in 1911. The window over the ark is by Louis Comfort Tiffany. It was installed in the 43rd Street Temple in 1899 in memory of Lewis May, the Congregation's longtime president. Originally, it was all one window, but when it was reinstalled here, it was divided into three sections separated by marble frames.

|

||

|

CHAPEL WINDOWS

Turning back to leave the chapel we see examples of the brilliant stained glass windows that adorn the clerestory and the rear wall. All windows in the Chapel other than the Tiffany window are the work of Nicola D'Ascenzo Studio, which was active until the late 20th century near Philadelphia Photographs © Don Hamerman 1996 |

||

A BRIEF HISTORYby Dr. Ronald B. SobelSenior Rabbi Emeritus

|

||

A PILGRIMAGE TO THE SITES

|

||

Part Two - Chrystie Street1848-1854

Emanu-El would not remain long in its first home. The membership was growing, slowly but steadily, and a permanent house of worship was needed. In October 1847, a church building at 56 Chrystie Street was purchased; its acquisition becoming the occasion for the adoption of a number of significant changes in ritual and liturgy. Early in 1848, the hymn books, containing German songs of Jewish content already in use, were printed. The same year saw the abolition of the one-year cycle of reading the Torah and the substitution for it of the three-year cycle. In 1849, the Bar Mitzvah ritual was changed with the students no longer permitted to read the entire Torah portion or even a section of it. The same year saw the installation of an organ and thereafter instrumental music accompanied the cantor and choir. New music was composed by the Congregation's hazzan. In 1851, the building of the sukkah in the Temple's courtyard was eliminated. In 1853, calling individuals to the reading of the Torah was abolished and thereafter the rabbi alone read from the Torah without the participation of worshippers. Although all these changes were accepted, though not without controversy, the sexes were still seated separately, the men below in the Synagogue with the women in a gallery above.

|

||

Part Three - East 12th Street1854-1866

Early in 1854, the Congregation made its first move uptown with the purchase of a lovely structure, a church building at 12th Street, which remains standing to this day. The members of the Congregation, though growing in number, did not yet possess sufficient financial resources to build their own house of worship. This move also became the occasion for changes in congregational tradition. Family pews were introduced in which men and women sat together. In 1855, Dr. Merzbacher authored Seder Tifilah, the second of four Reform prayer books to be published in the United States prior to 1860, and the first to have any wide, significant influence. With the exception of one German prayer recited at the Ark after the reading of the Torah, all the other prayers were spoken in Hebrew, though German language hymns were sung before the sermon and at the conclusion of the service. The choir, now better organized and composed of both men and women, played an ever increasing role during worship. On Rosh Hashanah, the shofar continued to be heard, but now to the accompaniment of instrumental music. In April 1854, a long debate began concerning the abolition of the second days of festivals. This change, reaching as it did to age-old custom but not law, was finally approved only after considerable discussion and in the face of much opposition. The children of the earliest members of the Congregation were, for the most part, born in New York and, unlike their parents, English was their first language. This created a need for someone fluent in English to assist the rabbi who spoke only German. In 1856, Dr. Merzbacher died. Since the German-speaking group at Emanu-El was still in the majority, the pulpit was filled by the election of Dr. Samuel Adler of Germany, one of the more important rabbinic authorities of 19th century Reform Judaism. The demand for English preaching, however, would not be silenced. In 1860, Dr. Adler radically revised the Merzbacher prayer book and further shortened the length of the Service.

|

||

Part Four - Fifth Avenue at 43rd Street1866-1927

In 1868, three years after the conclusion of the Civil War and twenty-three years following the organizing meeting of the Congregation, the members of Emanu-El were at last in a position to erect a sanctuary of their own, and a great sanctuary it was, at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 43rd Street. There the Temple was to remain for the next fifty- nine years. The dedication of the new Temple Emanu-El reflected the substantial economic and financial achievements of New York City's German Jews. When one remembers that less than a quarter century earlier thirty- three men with less than thirty dollars to contribute founded the Congregation, the achievement has to be included amidst the testimony that the United States, during the middle decades of the nineteenth century, was a land of opportunity where freedom allowed for new achievement, a nation where almost nothing seemed impossible. Journalists from the city's newspapers took note of the dedication and their reporting reflected admiration. On September 10, 1868, The New York Times announced the next day's event in the following manner: "The latest architectural sensation of this city is the splendid Jewish Temple Emanuel..." A leading New York City German language newspaper said of the Temple in describing the dedication: "The congregation counts the most prominent Jews of New York among its members. Their contributions to the new building, which cost over $650,000, were truly generous." The New York Daily Tribune was exceedingly laudatory in its reporting of the dedication: "A congregation composed of the very elite of our fellow citizens filled to repletion yesterday afternoon the new Jewish Temple Emanu-El. This is beyond doubt the most elegant Jewish house of worship in America, and is among the largest religious edifices in the city." The gradual Americanization of Temple Emanu-El continued, but it was not until the arrival of Dr. Gustave Gottheil, in 1873, from Manchester, England, that the Congregation solved its problems with regard to a permanent English-speaking rabbi. Additional liturgical and ritual changes took place in the 1870s and 1880s, among them the discard of head covering for male worshippers, the disappearance of the Bar Mitzvah ceremony and the introduction of a Sunday lecture in addition to the retention of the regular Sabbath morning worship. The original Merzbacher prayer book, extensively revised by Dr. Adler in 1860, continued in use until the adoption of the Union Prayer Book in 1895, which the congregation continues to use, in revised version, to this day.

|

||

Part Five - Fifth Avenue at 76th Street1891-1929

Dr. David Einhorn, one of the great intellectual architects of both European and American Reform Judaism was the founding rabbi of Congregation Beth-El. Organized in 1874, the new Temple was an amalgamation of two older New York synagogues, Anshe Chesed (founded in 1828) and Adas Jeshurun (founded in 1866). For several decades following its establishment, Anshe Chesed was Orthodox in practice and principle. Gradually, however, its members become influenced by the spirit of modernity, and there developed a tendency toward Reform. As was the case with Emanu-El, Adas Jeshurun began as a Reform congregation, founded by immigrants from Germany who came to this country with the hope of planting a Judaism both liberal in response to American democracy and simultaneously loyal to the inherited traditions of the Jewish past. Under the brilliant leadership of Dr. Einhorn, the two congregations become one in the creation of Temple Beth-El, with its house of worship located at Lexington Avenue at 63rd Street. The process of Americanization in Beth-El, concretized by ritual changes and liturgical innovations, paralleled, to a remarkable degree, the developments that were taking place about the same time at Temple Emanu-El. In 1879, Rabbi Einhorn was succeeded in the pulpit of Temple Beth-El by his son-in-law, Dr. Kaufmann Kohler, also an eminent theologian and scholar who, a quarter century later, would become President of the Hebrew Union College. Einhorn, Kohler and their successor, Dr. Samuel Schulman, bequeathed an indelible impress upon the ideas and ideals of American Reform Judaism. Growing in prosperity and recognizing the need for a larger house of worship the people of Beth-El erected a beautiful Temple on Fifth Avenue at 76th Street in 1891. Photographs of the Temple reveal that it was, in its time, one of the more beautiful buildings consecrated to religion in New York City. On April 11, 1927, Congregation Beth-El joined in union with Congregation Emanu-El, creating a house of worship that was soon to become world-renowned for its beauty and influence.

|

||

Part Six - Fifth Avenue and 65th Street1929-Present Louis Marshall, the Congregation's brilliant President from 1916 to 1929, stood as a towering figure in Temple Emanu-El and his influence pervaded virtually every aspect of Jewish life in this country and abroad. It was he who was the driving force behind the decisions to create the union with Temple Beth-El and move further northward on Fifth Avenue to 65th Street. Much had changed in New York City between the late 1860s and the mid-1920s. A majority of the Congregation's membership were living on the upper East and West sides. The character of Fifth Avenue near 43rd Street had altered; no longer residential, it was by then a noisy, commercial part of city life. The now "old" Temple, notwithstanding its beauty, had serious defects that could not be addressed. Marshall believed that the Congregation would be well served if it seized the opportunity to purchase the Astor mansion at 65th Street, a location convenient to all of Manhattan and an area guaranteed to remain residential as long as Central Park continues to exist. The members responded to both proposals favorably; they approved the merger with Temple Beth-El and they agreed to participate in the building of a new house of worship. Construction began in 1927 and the work was completed by the autumn of 1929. The formal Ceremony of Dedication on January 10, 1930, was an event of great significance not only for the people of Emanu-El and the Reform Jewish movement, but for American and world Jewry. The new Temple, the largest Jewish house of worship in the world, was the fruition of a spiritual contribution made to American Jewish life by a group of German Jewish immigrants whose religious activities began in 1845. Surely, among those present for the dedication were some who were impressed by the cost of the structure, the prestigious, outstanding location of the Temple in the city, and the skill with which modern art and science were combined to produce a masterpiece of architecture. There were others, no doubt, who were conscious of the fact that the new building mirrored the story of a certain group of immigrants to whom New York had extended protection and opportunity. To those sensitive participants, the lavish splendor of the Temple and impressive beauty of its Sanctuary must have constituted a thank-offering to America and to God.

|

||

|

Visiting in Person: The Sanctuary is open to the public. Tours are available Sunday through Friday. Please call the Temple Office to arrange group tours (212) 744-1400 Tours are also given after Morning Services on Saturday beginning at noon. For more information please contact info@emanuelnyc.org |

||

| Located within the confines of Temple Emanu-El is a jewel of Jewish culture - the Herbert and Eileen Bernard Museum of Judaica. Our museum collection features three galleries of Jewish art, religious ornaments and Temple memorabilia that are noted for their striking beauty and rarity. The Museum also sponsors an annual gallery lecture series and exhibitions, which seek to explore the intersections of Jewish identity, history and material culture. | ||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

links |

Special thanks to www.emanuelnyc.org | |