|

New York

Architecture Images-Upper East Side American Folk Art Museum |

|

architect |

Tod Williams Billie Tsien & Associates |

|

location |

East 53rd Street |

|

date |

2001 |

|

style |

Late Modern (International Style III) |

|

construction |

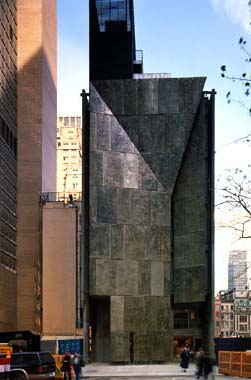

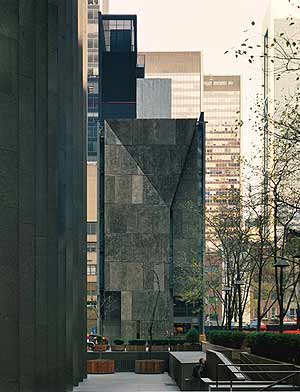

The façade of the 85-foot tall building is clad in sixty-three textured panels of a lustrous white bronze alloy known as Tombasil. The material—never before used architecturally—is faceted in three large planes that evoke the human hand and catch the light at different angles. A large skylight crowns a ceiling-to-floor open core, sending natural light through the entire height of the building. |

|

type |

Museum |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tombasil Panels on Facade | |

|

The American Folk Art Museum is the leading center for the study and enjoyment of American folk art, as well as the work of international self-taught artists. It is located at 45 West 53rd Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, in Midtown Manhattan (New York City, USA). Museum History The museum was founded on June 23, 1961, and opened its doors to the public for the first time on September 27, 1963, in the rented parlor floor of a townhouse at 49 West 53rd Street.[1] In 1979, the museum purchased two townhouses adjacent to 49 West 53rd Street. While plans for a development of these properties were being devised, the institution continued to present its exhibitions in the rented gallery until 1984, when it opened facilities in a former carriage house at 125 West 55th Street. That building, however, was razed just two years later, leaving the museum without galleries of its own for almost four years. During that time, the institution continued to organize a full schedule of exhibitions and educational programs, utilizing public spaces and corporate galleries, and offered an extensive traveling exhibition program to museums throughout the country. In 1989, exhibition facilities at 2 Lincoln Square, opposite Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, were opened. Diversity in programming became a growing emphasis for the institution in the 1990s. Major presentations of African American and Latino artworks became a regular feature of the museum's exhibition schedule and permanent collection. In 1998, the formation of the Contemporary Center was announced, a division of the museum that is devoted entirely to the work of twentieth- and twenty-first-century self-taught artists, as well as non-American artworks in the tradition of European art brut. Within a short time, the Contemporary Center established a leadership role in this field. In 2001, the Center announced the acquisition of twenty-four works by Chicago artist Henry Darger, as well as a huge archival collection of Darger’s books, tracings, drawings, and source materials, which combined now form the basis of the Henry Darger Study Center. As the collection and the reputation of the museum continued to mature, so did the effort to develop a permanent home. It was determined that the museum would erect a 30,000-square-foot, eight-level structure on the 45 and 47 West 53rd Street lots, to be designed by the internationally recognized firm of Tod Williams & Billie Tsien. This building was inaugurated on December 11, 2001. During the more than four decades of growth and development, the museum has enlarged its mission and extended the purview of its interests. Known initially as the Museum of Early American Folk Arts and concerned principally with the vernacular arts of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America, especially of the Atlantic Northeast, the institution adopted a simpler but more inclusive name in 1966: the Museum of American Folk Art. As an expression of a further extension of mission, the institution chose its current name, American Folk Art Museum, in 2001. Recognizing that American folk art could be fully understood only in an international context, the word American functions as an indication of the museum's location, emphasis, and principal patronage rather than as a limitation on the kinds of art it collects, interprets, or presents. In 2007, it was among over 530 New York City arts and social service institutions to receive part of a $20 million grant from the Carnegie Corporation, which was made possible through a donation by New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg.[2] Artworks and Exhibitions The museum began to build a collection almost immediately after it was established. The now iconic Flag Gate (c. 1876) was its initial accession, in 1962, followed, a year later, by the Archangel Gabriel Weathervane (c. 1840) and the monumental St. Tammany Weathervane (c. 1890), now a centerpiece in the museum. The purchase, in 1979, of the famous Bird of Paradise Quilt Top (1858–1863) represented a turning point: The art of quiltmaking would become a major emphasis in the collection and public programs of the institution. Throughout the 1980s, the permanent collection continued to grow with major acquisitions of early American folk art, including Ammi Phillips’s masterpiece, Girl in Red Dress with Cat and Dog (1830–1835). Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, the institution was recognized for its lively exhibitions, many of which were pioneering in scope, including the wide-ranging and influential "Twentieth-Century American Folk Art and Artists" in 1970, which explicitly took a broader view of the field than that originally articulated by the organization's founders. In this and other exhibitions, the museum argued against the notion that the creation of folk art was a thing of the past. In anticipation of the completion of the new building in 2001, more than four hundred important works of early American folk art from the renowned collection of Ralph O. Esmerian were promised to the museum. These included a comprehensive collection of Pennsylvania German material, Shaker gift drawings, needlework samplers, and paintings by artists such as Edward Hicks and Sheldon Peck. Recent exhibitions include: "A Legacy in Quilts: Cyril Irwin Nelson's Final Gifts to the American Folk Art Museum" (2007–2008) "Gilded Lions and Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue to the Carousel" (2007–2008) "The Great Cover-up: American Rugs on Beds, Tables, and Floors" (2007) "In the Atrium: Landscapes from the Collection" (2007) "Martín Ramírez" (2007) "A Deaf Artist in Early America: The Worlds of John Brewster, Jr." (2006) "Concrete Kingdom: Sculptures by Nek Chand" (2006) “White on White (and a little gray)” (2006) "Obsessive Drawing" (2005–2006) "Surface Attraction: Painted Furniture from the Collection" (2005–2006) "Ancestry and Innovation: African American Art from the Collection" (2005) "Self and Subject" (2005) "Blue" (2004–2005) Upcoming exhibitions: "Darger-ism: Contemporary Artists and Henry Darger" (2008) "Asa Ames" (2008) Building History The striking building now housing the American Folk Art Museum allows the institution to display more than five hundred artworks from its collection of more than five thousand objects. The façade of the 85-foot tall building is clad in sixty-three textured panels of a lustrous white bronze alloy known as Tombasil. The material—never before used architecturally—is faceted in three large planes that evoke the human hand and catch the light at different angles. A large skylight crowns a ceiling-to-floor open core, sending natural light through the entire height of the building. Intimate areas, reflecting the domestic scale of much of the museum's collection, allow for a personalized art experience. Open galleries feature spaces for the display of larger, more dramatic works. A unique cantilevered concrete stairway connects all levels of the building. Additional types of staircases not only provide varied paths of circulation between floors but also give visitors different visual experiences. Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects have won numerous awards for the building—among others, an American Institute of Architects National Honor Award (in 2003); the World Architecture Awards for Best Building in the World, Best Public/Cultural Building in the World, and Best North American Building, as well as the New York City American Institute of Architects Design Award (all in 2003); and the Municipal Art Society New York City Masterwork Award (in 2001). References ^ For more information about the history of the American Folk Art Museum, see Gerard C. Wertkin, "Foreword," in Stacy C. Hollander and Brooke Davis Anderson, American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum (New York: American Folk Art Museum in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001), pp. 10–13. ^ New York Times: City Groups Get Bloomberg Gift of $20 Million. Retrieved on September 3, 2007 ^ See "A Selection of Awards," Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects official website. Further Reading Folk Art. Magazine published annually by the American Folk Art Museum. Anderson, Brooke Davis. Darger: The Henry Darger Collection at the American Folk Art Museum. New York: American Folk Art Museum in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001. Anderson, Brooke Davis. Martín Ramírez. Seattle: Marquand Books in association with American Folk Art Museum, 2007. Hollander, Stacy C. American Radiance: The Ralph Esmerian Gift to the American Folk Art Museum. New York: American Folk Art Museum in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001. Hollander, Stacy C., and Brooke Davis Anderson. American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum. New York: American Folk Art Museum in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001. Zimiles, Murray. Gilded Lions and Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue to the Carousel. With a foreword by Gerard C. Wertkin and an essay by Vivian B. Mann. Lebanon, N.H.: University Press of New England/Brandeis University Press in association American Folk Art Museum, 2007. |

|

|

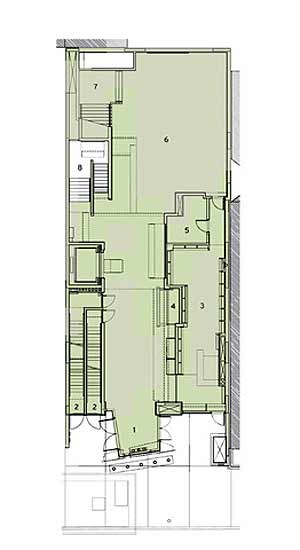

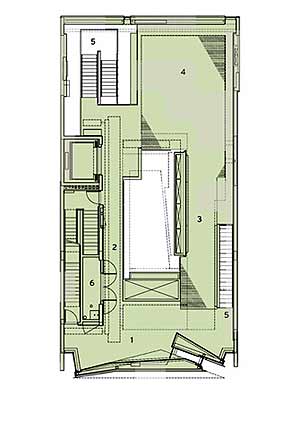

American Folk Art Museum Chartered as the Museum of Early American Folk Arts when it was founded in 1961, the Museum originally focused on the vernacular arts of 18th and 19th century America, especially of the northeast. The institution adopted a more inclusive name – Museum of American Folk Art – in 1966. Over the years, it established a national and international reputation as a leading cultural institution dedicated to the collection, exhibition, and study of traditional and contemporary American folk art. As the American Folk Art Museum, it will present exhibitions and programs that embrace an even wider range of folk art, both traditional and contemporary, from the U.S. and abroad. Name Change In anticipation of this major expansion and to underscore a spirit of dynamic growth, the Museum is changing its name to American Folk Art Museum. The new name emphasizes the American experience within a global mission. The American Folk Art Museum’s Inaugural Season of Exhibitions, launched with the opening of the new building, will illustrate the Museum’s commitment to an expanded range of interests from traditional folk art of the 18th and 19th centuries to the work of contemporary self-taught artists from the U.S. and abroad. “The name change marks the beginning of a new and exciting chapter in the 40-year history of this institution as we eagerly await the completion of the expansion,” said Gerard C. Wertkin, director of the American Folk Art Museum. “The new name makes a subtle but significant difference, reflecting our mission as America’s foremost institution dedicated to promoting the knowledge and appreciation of folk art from this country and abroad, past and present.” The American Folk Art Museum’s increasingly broadened outlook has been evident in a series of rotating exhibitions organized by the Museum over the past several years, including exhibitions on the folk art of Latin America, England, and Norway, among other countries and continents. The Museum is currently presenting the work of 20th century European and American self-taught artists who fit French artist Jean Dubuffet’s definition of art brut. A number of paintings by artists represented in the exhibition ABCD: A Collection of Art Brut have already entered the Museum’s permanent collection. At the Museum by Jason Wiggins The American Folk Art Museum is small and can be somewhat hard to find. The museum’s permanent exhibit has a diverse range of objects, quilts, hunting decoys, portraits, decorative pottery and boxes, weathervanes and religious objects, paintings and crucifixes; basically, artwork that you most likely won’t find in other museums of American art. There’s a lot of information explaining the history and importance of the work, but even if you stop to read everything, you won’t end up spending more than two hours here. The staff of the museum is friendlier than those of a lot of other museums, making it a pleasure to visit. About the New Building The new building will quadruple the Museum’s gallery space for the display of its expanded permanent collection and special exhibitions, provide educational facilities, and consolidate the staff offices. Tod Williams Billie Tsien and Associates’ first major public project in New York City, the new facility will fulfill the Museum’s long-term goal of establishing a permanent home for the study and appreciation of American folk art and allow the Museum to display a substantial number of artworks from its collection of 4,000 objects. It will also be home to the Museum’s Contemporary Center, dedicated to the study and appreciation of the work of contemporary self-taught artists. The Museum will continue operating its current gallery space, the Eva and Morris Feld Gallery at Lincoln Square, as a branch museum, ensuring a significant presence in two of New York’s most important cultural districts—the Lincoln Center area and midtown Manhattan, near the Museum of Modern Art, the American Craft Museum, and the Museum of Television & Radio. Clad in sixty-three lightly textured tombasil panels, a white bronze alloy, the eight-level, 85-feet tall structure will be capped by a skylight above a grand interior stair connecting the third and the fourth floor, with dramatic cut-throughs at each floor to allow natural light to filter into the galleries and through to the lower levels. The lustrous, sculptural facade is the product of a manual fabrication process evocative of the hands-oriented approach characteristic of folk art—its panels are cast by pouring molten metal directly into gated forms on the concrete floor of the foundry. The faceted panels, which appear stonelike and metallic at the same time, will create different visual effects catching the light of the sun as it rises and sets, east and west along 53rd Street. The galleries on the four top floors of the building will vary in scale from intimate spaces to open areas to allow for a personalized art experience and the display of larger works. Art will also be integrated into public spaces, such as the lobby, stairwells, and hallways, utilizing a system of niches throughout the building that offers interaction with a changing group of folk art objects beyond the gallery setting. Visitors will be able to move between building levels by using three different staircases – a layout that encourages multiple paths of circulation and gives the visitor the feeling of an architectural journey. Adding a sense of warmth to the building, the gallery floors will be made of wood set into concrete. Seven of the eight levels of the new building will be entirely dedicated to public space. The mezzanine level will house a small coffee bar overlooking a two-story atrium and offering views of 53rd Street. At the entrance level will be the Museum Shop, with access during non-Museum hours via a separate exit to the street. The museum offices, reference library, and educational areas, including an auditorium and classrooms, will be located on two levels below ground. The $34.5 million Capital Campaign to fund the expansion project and boost the Museum’s endowment has been spearheaded by Ralph Esmerian, Chairman of the Board, and Lucy Cullman Danziger, Campaign Chair and Board Executive Vice-President, under the presidency of John Wilkerson. To date, the Museum has successfully raised $31 million from private, public, and foundation sources, including $2.5 million appropriated by The City of New York and $500,000 by the State of New York in support of the new building. Museum History After many years of planning, the museum is opening a magnificent new building at 45 West 53rd Street in Manhattan; at the same time, the organization is seeing the most significant additions to its permanent collection in the forty years since its founding. As a result, it seemed appropriate for me to take a broad, backward look at the institution as it embraces the long-awaited realization of the very goals that sparked its establishment. I do not intend this essay to be a history of the museum, but rather a review of some of the highlights of a fascinating forty-year story of commitment and courage. Founding Trustee Adele Earnest contributed her “History of the Museum, 1961-1978” to the midsummer 1978 issue of The Clarion (now Folk Art magazine). In the winter 1989 issue, Alice J. Hoffman—now the museum’s director of licensing—published her comprehensive study, “The History of the Museum of American Folk Art: An Illustrated Timeline.” Both of these resources remain valuable introductions to the museum, and I am happy to acknowledge my reliance upon them in the preparation of this essay. The First Decade, 1961-1971 The museum’s first decade was a time of multiple beginnings, as its founders—Adele Earnest, Cordelia Hamilton, Herbert W. Hemphill Jr., Joseph B. Martinson, Marian Willard Johnson, and Arthur M. Bullowa—sought to give shape and structure to a shared vision. For them, folk art was a vital element in American cultural history, and it warranted the establishment of an institution in the city of New York devoted to its collection, exhibition, and interpretation. When the Board of Regents of the New York State Education Department granted a provisional charter on June 23, 1961, the prospects for acquiring a home or a collection for the Museum of Early American Folk Arts, as the new organization was initially called, were uncertain at best. The choice of New York City, then acknowledged as the art capital of the world, was significant in itself. The very idea that folk art could be studied and appreciated as art, rather than as material culture or historical or ethnographic artifact, was a by-product of the growth of modernism as a movement in the history of American culture. The museum began to build a collection almost immediately after it was established. Hemphill presented the now famous Flag Gate (c. 1876) as a gift in 1962. The museum’s initial accession, this piece remains among the most celebrated works of art in the permanent collection. Adele Earnest contributed the Archangel Gabriel weathervane (c. 1840) the following year. Featured as the cover image on the catalog of the institution’s first exhibition, which was on view in the gallery of the Time and Life Building in October and November of 1962, the weathervane served as a well-loved symbol of the museum for many years. During its first decade, other gifts also came to the museum, along with one major purchase: the monumental, 9-foot-tall St. Tammany weathervane (c. 1880), perhaps the country’s largest. With a handful of exceptions, the institution’s earliest acquisitions were three-dimensional objects. The museum soon established a reputation for the visual strength and aesthetic importance of sculpture in its permanent collection, a reputation that was enhanced in 1969 by Alastair B. Martin’s gift of 140 outstanding wildfowl decoys. Its other holdings were, relatively speaking, minor. The museum opened its galleries to the public for the first time on September 27, 1963, in the rented parlor floor of a town house at 49 West 53rd Street. George Montgomery, who had organized traveling exhibitions for the Museum of Modern Art, was appointed the museum’s first director in 1963, a post he held only until 1964. For the most part, the institution’s approach to the collection and exhibition of American folk art was grounded in the fine arts, following—but extending—the model of curator Holger Cahill, whose groundbreaking exhibitions at the Newark Museum and the Museum of Modern Art in the 1920s and 1930s helped establish the field. The exhibition program of the first decade was ambitious. Although the museum’s emphasis, as might be expected, was on the nineteenth century and the Northeast, the institution staked out a national and even international purview for itself almost from the beginning. Although it consistently received excellent reviews for its exhibitions, many of which were truly pioneering in scope, subject matter, and scholarship, the institution’s goal of financial stability remained elusive. Even so, the museum continued to present provocative and engaging exhibitions. The new museum established a reputation for its innovative programming and fidelity to mission. Its success in fulfilling its objectives was recognized by the Board of Regents in 1966, when it awarded a permanent charter to the institution under the name Museum of American Folk Art. Nevertheless, the decade ended in doubt and even despair. Due to financial difficulties, the Board of Trustees considered closing the institution’s doors forever in 1971. The Second Decade, 1971-1981 If there were few reasons to celebrate the beginning of the museum’s second decade, there were at least several reasons for encouragement. A grant from the National Endowment for the Arts funded a series of exhibitions that helped sustain the museum’s reputation as an innovator and drew more visitors than any of the exhibitions held during the institution’s first decade. The museum also received a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts; this funded the planning and organization of a series of Bicentennial exhibitions on the folk arts of New York State. Wallace E. Whipple, director from 1971 to 1972, explained that the many encouraging developments masked a more serious reality, and the financial strain on the institution was intense. Consideration was given to the sale of the museum’s collection at auction. This was a controversial proposal; ultimately, the museum retained ownership of the most important works of art in its collection. The brief but brilliant directorship of Bruce Johnson (1975-1976) helped bring a renewed sense of purpose to the organization. Shows presented during his tenure broke all attendance records. The museum also produced a series of illustrated catalogs and books during this period. The momentum that Johnson inspired continued beyond his tragic death in a motorcycle accident at the age of twenty-seven. One of the museum’s new trustees of that time was Ralph Esmerian, a young collector whose name appears in museum records for the first time in 1973. Esmerian entered an uncertain institutional environment with the conviction that the institution not only would survive but, if properly nurtured, would build a national center in New York for the study and appreciation of American folk art. He served as treasurer until 1977, as president from 1977 to 1999; since 1999, he has served as chairman. In 1977, the museum’s Board of Trustees appointed Robert Bishop director. Bishop was a talented promoter who took a broad, inclusive view of folk art. A prodigious author in the fields of the American folk and decorative arts, Bishop placed great emphasis on the museum’s publication program. The summer 1977 issue of The Clarion was no longer a newsletter; in addition to providing a glimpse of the museum and its programming, it featured topical essays on a variety of aspects of American folk art. It would soon be recognized as an important resource for the study of the subject and help boost membership in the museum. In order to encourage gifts to the museum, Bishop set an example by promising works of art from his own collection. In 1978, one year after he arrived at the museum, Bishop boldly published “A Guide to the Permanent Collection” in the midsummer issue of The Clarion. Many of the objects illustrated in the article were his own promised gifts; others were the gifts or promised gifts of his friends and associates, including Trustee Cyril I. Nelson. For the first time since its founding, the museum now held a collection of quilts and other textiles, and this collection would soon become one of its greatest strengths. Also, the collection now included paintings and sculpture by twentieth-century self-taught artists. Another successful initiative of Bishop’s early years was the establishment of the museum’s volunteer docent program in 1978. Lucy Cullman Danziger, now executive vice president of the museum’s Board of Trustees and chair of its Capital Campaign, initially served as a founding docent and as docent co-chair. In 1979, several trustees came together to purchase the famous Bird of Paradise Quilt Top (c. 1860) for the museum. Another major acquisition was David Pottinger’s gift in late 1980 of his comprehensive collection of midwestern Amish quilts. During the same year, the Museum received Effie Thixton Arthur’s bequest of her large collection of chalkware figures. Most celebrated of the accessions during this period was a highly significant promised gift, the collection of figural sculpture assembled over many years by Dorothea and Leo Rabkin. Although it still had a long way to go, the museum was clearly building a permanent collection of true substance and depth. Because of the inadequate size and facilities of its rented gallery, the museum sought to move into a home of its own almost from its earliest days as an institution. In 1979—through an introduction from Maureen Taylor, a trustee of the museum, and her husband, Richard, a former trustee, and the interest of Blanchette Rockefeller—the museum was able to purchase from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund two adjoining town houses at 45-47 West 53rd Street, formerly a residence for actresses called the Rehearsal Club. This purchase would prove to be one of the single most significant events in the history of the institution. Although the buildings were in poor condition and thus could not be used, they provided the basis for future development. Through the generosity of Ralph Esmerian, the principal contributor of funds toward this purchase, and other thoughtful members of the Board, the museum could now look forward to a home of its own. If the second decade began in doubt and uncertainty, it ended on a very high note, indeed. The Third Decade, 1981-1991 When I joined the staff of the museum as assistant director in late 1980, it became clear that the building project was the principal order of the day. The museum began to devise plans for development on West 53rd Street—an effort that dominated its third decade. These plans were complicated by a series of zoning, tenant, and legal issues that absorbed the time and attention of the museum’s board and administration. To be sure, the museum continued to organize a full and varied schedule of exhibitions and educational programs. In 1981 the museum established a graduate program in folk art studies in conjunction with New York University, the first of its kind in the nation. The Folk Art Institute, an accredited program leading to a certificate in folk art studies, was initiated in 1985. The decade also witnessed impressive growth in the permanent collection, but the development of the museum’s future home took precedence over everything else. The museum presented its exhibitions at 49 West 53rd Street until 1984, when it opened handsome new facilities nearby in a former jazz museum and Rockefeller carriage house at 125 West 55th Street. This was a temporary move, an optimistic response to affirmative developments in the building program, intended in part to permit the properties on 53rd Street to be prepared for demolition. Under the terms of the lease covering the 55th Street galleries, the museum was required to vacate in 1986 (the building was subsequently razed). Without galleries of its own for almost four years, the institution organized a remarkable series of exhibitions and educational programs by utilizing public spaces and corporate galleries and forming partnerships with other museums. In addition, the museum strengthened and extended its traveling exhibition program to institutions throughout the country. As of the end of the museum’s fourth decade, its exhibitions have been presented in no fewer than 150 museums and other venues in the United States and abroad, representing both a major public service and a professional affirmation of the merit of the museum’s programming. While negotiations on the future of the museum’s properties on 53rd Street continued, the museum undertook the creation of branch exhibition facilities at Two Lincoln Square in Manhattan, on the ground floor of a multi-use building opposite Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. Occupied under a tripartite agreement with the owner of the premises and the City of New York, this former “public arcade” provided more expansive exhibition space than either of the institution’s prior galleries. It opened to great fanfare in 1989. Named for the renovation’s principal contributor and her late husband, the Eva and Morris Feld Gallery at Lincoln Square has supported a broad-based public program since it was opened twelve years ago. Back in 1980, Bishop and I began a series of talks with Jean and Howard Lipman for the purchase of their collection of American folk art. As a result, the museum accessioned thirty-nine key works and sold the remainder at auction to fund the purchase. Among other significant accessions during the museum’s third decade, Elizabeth Ross Johnson contributed a group of twentieth-century paintings and sculpture in 1985. The same year, Animal Carnival, Inc., through Trustee Elizabeth Wecter, transferred a collection of animal sculptures. Martin and Enid Packer’s collection of tenth-anniversary tin arrived in 1988, and in 1989 Margot Paul Ernst gave her woven coverlet collection in memory of Susan B. Ernst. That same year, an encyclopedic gathering of painted tinware and other objects, the gift of the Historical Society of Early American Decoration, also came to the institution. The expected development of a multi-use building on six lots—upon which so much energy was expended during the decade—did not occur. The project had to be scuttled. That fact, and Robert Bishop’s increasingly serious illness, cast a shadow over the end of the museum’s third decade. The museum’s thirtieth anniversary passed with little notice. The Fourth Decade, 1991-2001 Robert Bishop died on September 22, 1991, and was deeply mourned by a wide circle of friends and professional associates. After serving as acting director during Bishop’s illness, I was appointed director of the museum in December of that year. My goals as director included a renewed focus on the building program, greater diversity in exhibitions and collections, more sustained use of the permanent collection, and a concentration on new scholarship. The board, the staff, and I entered a period of long-range planning and self-study to help prepare for the realization of these objectives. Over the course of the first thirty years of its history, the museum’s programming was remarkably diverse—indeed, by its very nature the folk art field is multicultural—but diversity became even more of an emphasis in the 1990s. Major presentations of works by African American and Latino artists became a regular feature of the museum’s exhibition schedule and permanent collection. In 1991, a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts funded the purchase of an important collection of contemporary African American quilts. In 1993 the museum rededicated the south wing of the Eva and Morris Feld Gallery at Lincoln Square as the Daniel Cowin Permanent Collection Gallery, so named in memory of a deeply respected trustee. In 1998 I announced the formation of The Contemporary Center, a division of the institution devoted entirely to the collection and exhibition of the paintings, sculpture, and installations of twentieth- and now twenty-first century self-taught artists. Its establishment prompted the gifts to the museum of important works by twentieth-century self-taught artists from M. Anne Hill and Edward Vermont Blanchard, Sam and Betsey Farber, and David Davies. In 2001, The Contemporary Center announced the acquisition, by purchase and by gift, of twenty-four works by the great Chicago artist Henry Darger, as well as a huge archive of Darger’s manuscript books, tracings, drawings, and source materials. Although the Eva and Morris Feld Gallery greatly improved its capacity to serve the public in the 1990s, the museum persisted in its efforts to create a permanent home and determined to develop a new building on the lots at 45 and 47 West 53rd Street. The museum’s trustees commissioned the internationally recognized architectural team of Tod Williams Billie Tsien and Associates to design a 30,000-square-foot structure on the two lots, and they announced the commencement of a $34.5 million Capital Campaign to underwrite the costs of construction and the establishment of an endowment. Known initially as the Museum of Early American Folk Arts, the institution adopted a more inclusive name in 1966; as the Museum of American Folk Art, it established a reputation for examining virtually every aspect of the folk arts in America. The museum has now chosen its new name, the American Folk Art Museum, as an expression of a further extension of mission. In anticipation of the opening of the museum’s new home, many thoughtful donors have given or promised highly important objects in virtually every medium for the permanent collection. Indeed, the growth of the permanent collection has been a striking feature of the 1990s. The most significant gift comprises more than four hundred works of art representing the heart of Ralph Esmerian’s folk art collection. Founding trustee Adele Earnest struck a millennial note seventeen years ago in the concluding paragraph of her book Folk Art in America. Although she herself did not live to see the realization of her dream, she fully anticipated its fulfillment. “When I climb the hill near my home in Stony Point,” she wrote, “I will look straight down the Hudson River, thirty miles to New York City where our [museum] shall stand. On that triumphant day, our Angel Gabriel will blow his horn, loud and clear, in honor of all who have served our cause, and especially for those who have served and passed through the pearly gates. Blow! Gabriel! Blow!” Excerpts from an essay published in Folk Art (summer 2001, vol. 26, no. 2), the museum’s quarterly magazine. Awards The American Folk Art Museum is pleased to announce that its building at 45 West 53 Street, designed by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects, continues to receive awards for its magnificent design. Most recent honors include the American Institute of Architects National Honor Award and the NYACE Engineering Excellence Award, both of which were received in 2003. The American Folk Art Museum was awarded the prestigious Arup World Architecture Award, a top international prize, for "Best New Building in the World for 2001." The Museum was chosen among 300 international projects completed during 2001. Entries came from 45 countries, and included a wide range of types and sizes of buildings–from some of the world’s best-known architectural firms to small one-person practices. New York City-based architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien joyously accepted the $30,000 award for their design at a ceremony in Berlin on Friday evening, July 26, 2002. The American Folk Art Museum also won the award for "Best North American Building" and "Best Cultural Building in the World." The Awards are organized by World Architecture Magazine and were judged by a panel of leading architectural experts, drawn from all around the world. “All of us at the museum are delighted that Tod Williams and Billie Tsien have received this important professional recognition for a design that captures the very essence of creativity which forms the core of the museum’s mission,” said Gerard C. Wertkin, director of the American Folk Art Museum. “Their magnificent new building provides a perfect setting for the museum to present the great works of art that comprise our collection.” The American Folk Art Museum opened December 11, 2001 to great critical and public acclaim. Coinciding with the three-month anniversary of the terror attacks on the World Trade Center, the unveiling of the new building represented progress, growth, and renewal during a city-wide effort to revitalize New York’s cultural, social and economic life. It is the first new art museum built from the ground up since the Whitney Museum of American Art opened in 1966. “This may not be a big building—by American standards—but it is a magnificent one. The design is a very interesting response to New York, where building are usually so glassy. Here there is a real weightiness; it suggests a different take on contemporary architecture,” noted Naomi Stungo, the editor of World Architecture magazine who presented the award. About the Building The 30,000 square foot building is clad in sixty-three lightly textured tombasil panels (a white bronze alloy). An eight-level, 85-foot tall structure, it is capped by a skylight above a grand interior stair connecting the third and the fourth floors, with dramatic cut-throughs at each floor to allow natural light to filter into the galleries and through to the lower levels. The lustrous, sculptural facade is the product of a manual fabrication process evocative of the hands-oriented approach characteristic of folk art – its panels are cast by pouring molten metal directly into gated forms on the concrete floor of the foundry. The faceted panels, which appear stonelike and metallic at the same time, create different visual effects catching the light of the sun as it rises and sets, east and west along 53rd Street. The galleries on the four top floors of the building vary in scale from intimate spaces to allow for a personalized art experience to open areas for the display of larger works. Art is also integrated into public spaces, such as the lobby, stairwells, and hallways, utilizing a system of niches throughout the building that offers interaction with a changing group of folk art objects beyond the gallery setting. Visitors are able to move between building levels by using three different staircases – a layout that encourages multiple paths of circulation and gives the visitor the feeling of an architectural journey. Adding a sense of warmth to the building, the gallery floors are made of wood set into concrete. Seven of the eight levels of the new building are entirely dedicated to public space. The mezzanine level houses a café overlooking a two-story atrium and offering views of 53rd Street. At the entrance level is the Museum Shop, with access during non-museum hours via a separate exit to the street. The museum offices, reference library, rare book room, and educational areas, including the auditorium and classrooms, are located on two levels below ground. http://www.twbta.com/ In the words of architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, the following statement documents what it takes to “build a museum” from vision to completion. This new eight-level building devotes the four upper floors to gallery space for permanent and temporary exhibitions. A skylight above a grand interior stair allows natural light to filter into the galleries and to the lower levels through openings at each floor. As a result, dramatic interior spaces are animated by a wash of light, enhancing the experience of the visitor. Art has been built into the structure and circulation paths of the building using a series of niches that offer informal interaction with a changing selection of folk art. The experience of the museum visitor is conceived as a personal journey composed of surprise encounters with both new and familiar objects through the use of diverse paths. The museum’s collections and exhibitions are presented through traditional and non-traditional display spaces, creating a memorable environment for frequent as well as first-time visitors. At the mezzanine level, a small café overlooking 53rd Street provides a dramatic view of the two-story atrium. The building extends two levels underground; one floor holds the new auditorium and classroom facilities, while the lowest level houses administrative offices and the library. At the street level is a new museum store accessible during non-museum hours via a separate entrance. This forty-foot-wide building is surrounded on the front and back sides by sites owned by the Museum of Modern Art. The facade of the American Folk Art Museum is designed to make a strong but quiet statement of independence. It is sculptural in form, recalling an abstracted open hand that folds slightly inward to create a faceted plane. Metal panels of tombasil, a form of white bronze, clad the building. Spaces between each panel reveal the darkened wall of the weather barrier behind. These panels catch the glow of the morning and early evening sun as it rises and sets, east and west along 53rd Street. Facade Panels When first asked what the facade of the museum might be, our rather facetious response was that it might be made of old bubble gum. The second impulse was to consider tilt-up concrete panels cast on the vacant lot next door to our site. One could imagine the layers of urban archeology that could be uncovered and incorporated into the facade of the building. Obviously, both these ideas were not realistic, but they revealed our desire to clad the building in a material that was both common and amazing, and that would show a connection with the handmade quality of folk art. We wanted the building to reflect the direct connection between heart and hand. Tombasil We decided to look for a material that had a warmer color. Tombasil is a commercially produced white bronze alloy used for boat propellers, fire hose nozzles, and grave markers (hence its name). It has a warm yet silvery quality that we liked. We were interested in the direct fabrication technique; one that revealed how the panels were made. Samples were made at first by pouring the material directly onto the concrete floor of the foundry. We also tried pouring tombasil onto steel plates for a smoother finish. Although the results were interesting, they were also uncontrollable. The intense heat of the molten metal caused water entrapped in the concrete to explode; the results were interesting pockmarks but dangerous working conditions. The heat also caused the steel plates to warp and buckle. Working with the Tallix foundry in Beacon, New York, we eventually developed a more controlled situation using sand molds taken from concrete and steel. Resin fiberglass We previously used fiberglass in an installation of screens that we had designed. We very much liked the translucency and its “low tech” quality. Originally, we wanted to use a screen wall of fiberglass to shield the primary staircase. The screen would create silhouettes of people walking up and down the stairs. We wanted the screen to be blue. However, since it was a permanent part of the building, the fiberglass needed to be fireproofed, a process that would have produced a murky brown tone. The samples show how the color changed as we worked with the fabricator to produce what eventually became the blue-green panels. Pietra Piesentina This stone comes from a small quarry north of Venice. The stone occurs as large boulders that are dug out of the earth and cut into more standard rectangular blocks. In northern Italy pietra piesentina is used for paving as well as for exteriors and interiors. In the museum, it is used on the floors and walls of the lower, ground, and mezzanine levels in a flamed or roughened finish. The stone’s warm gray tone complements the concrete used throughout the building and creates a contrast to the cool blue-green tone of the fiberglass. Douglas Fir The materials of the museum are a balance of warm and cool. To counter the coolness of the concrete and glass, many elements throughout the museum are made of Douglas fir, which has a warm reddish hue. Solid, full-length fir planks are set into terrazzo ground concrete in the gallery spaces. Solid wood rails run along the glass handrails. This same wood is also used in a woven manner as a balustrade wall separating the café (on the mezzanine level) from the ground level of the museum. It also appears as a series of fins along the wall of the auditorium. Laminated Insulated Glass An extremely clear glass, Starfire, manufactured by Pittsburgh Plate Glass, was chosen for the windows. Glass usually has a green tint to it, which causes both light entering the building and views out of the building to have a greenish quality. To keep views of the city true to their color, this special transparent glass was used. Concrete The concrete throughout the museum has been finished using different techniques; although the material stays the same, it varies in color and finish. The slabs throughout the building are terrazzo ground to produce a smooth finish that reveals the stone aggregate. The poured–in–place concrete walls are bush hammered. This technique involves using a jackhammer over the surface, which creates a rough but controlled texture. Cold Rolled Steel The handrails along the main stair, which runs from the top to the bottom of the gallery spaces, are fabricated from blued cold rolled steel. We chose the steel because it is both humble and elegant. Terne-Coated Stainless Steel The exterior of the north facade of the building is finished with thin sheets of steel. They are used in an overlapping manner, rather like enlarged shingles, to create both depth and texture. Heath Tile Terra Cotta Hand-Glazed Tile The Heath Company started as an art ceramics studio in Sausalito, California, fifty years ago. The entry and the interior walls of the bathrooms are finished using their white tile. Each tile is hand glazed, which causes variations in the final color. Cherry Benches in the gallery and tables in the library are custom made by cabinetmaker Steven Lino from cherry wood. Cherry is similar in color to the Douglas fir, but it is a deeper red and a harder wood. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES The work of Tod Williams Billie Tsien and Associates bridges different worlds - across theory and practice; across architecture and the fine arts. Williams had a seasoned foundation in the practice of architecture with over six years as an associate in the office of Richard Meier before starting his own practice in 1974. Tsien brings to architecture a background in the Fine Arts and a keen interest in crossing disciplinary boundaries. Both architects maintain active teaching careers parallel to their practice. Tsien has taught at Parsons School of Design, SCI-ARC, Harvard, Yale, and UT Austin. Williams has taught at the Cooper Union, SCI-ARC, Harvard, Yale, and UT Austin and held the Thomas Jefferson chair at the University of Virginia in 1990. They shared the Jane and Bruce Graham chair at Penn in 1998. Billie Tsien is on the boards of the Architectural League, the Public Art Fund, and is a vice president of the Municipal Art Society in New York City. Tod Williams is on the advisory board of the School of Architecture at Princeton. |

|

|

Among several awards the American Folk Art

Museum was selected "Best New Building in the World for 2001" and in

October, 2002 the building was awarded the prestigious Brendan Gill

Prize by the Municipal Art Society of New York. Area: 30,000 square feet Completed: 2002 Client: The American Folk Art Museum ( www.folkartmuseum.org ) Architects: Tod Williams Billie Tsien, Architects Project Architect: Matthew Baird Project Team: Phillip Ryan Jennifer Turner Nina Hollein Vivian Wang Hana Kassem Kyra Clarkson Andy Kim William Vincent Leslie Hanson Associate Architect: Helfand Myerberg Guggenheimer Architects Project Team: Peter Guggenheimer Jennifer Tulley Jonathan Reo Director: Gerard C. Wertkin Deputy Director: Riccardo Salmona Project Manager: Seamus Henchy & Associates Seamus Henchy Chris Norfleet Kristen Solury General Contractor: Pavarini Construction Acoustical Consultant: Acoustic Dimensions Structural Engineers: Severud Associates Mechanical Engineers: Ambrosino, DePinto & Schmeider Curtainwall Consultant: Gregory Romine Lighting Design: Renfro Design Group Exhibition Design: Ralph Appelbaum and Associates Graphic Design: Pentagram Bronze Panel Foundry Tallix Concrete Consultant: Reginald Hough FAIA With thanks to www.arcspace.com for construction notes. Full article at; http://www.arcspace.com/architects/williams_tsien/american_folk/index.htm

|

|

|

links |

http://www.folkartmuseum.org |