|

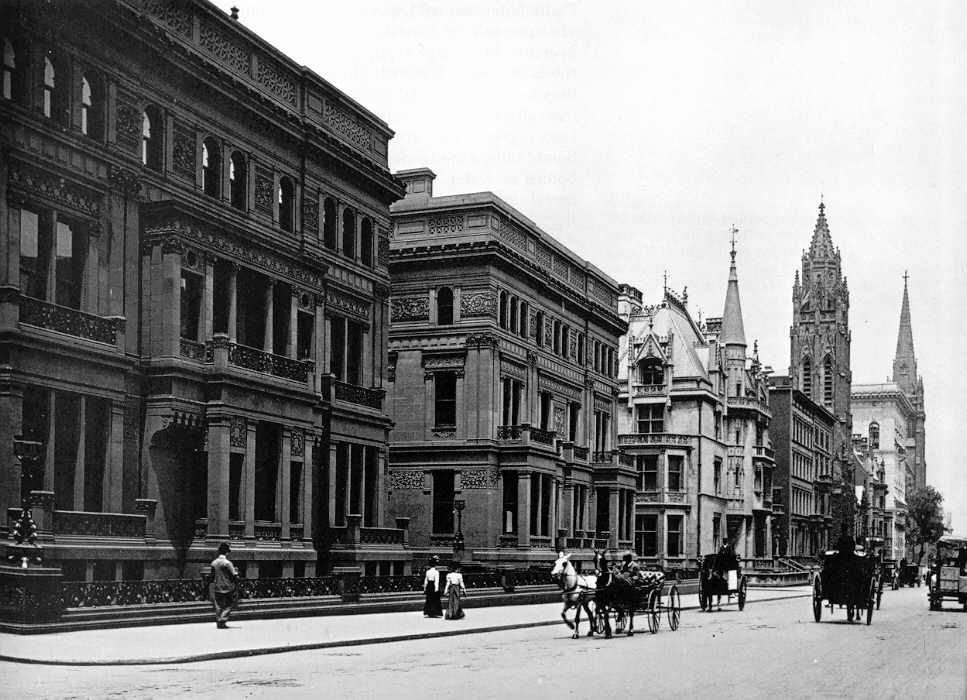

Richard Morris Hunt was the first American to

study at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and, after his return to New

York, he became the most prominent architect in the city. Early in his

career, Hunt designed a series of avant-garde buildings, introducing

French architectural ideas to America. These include the Stuyvesant

(1870–73; demolished), the earliest apartment house planned for the

middle class, the Roosevelt Building (1873–74), a cast-iron building

with a clearly expressed structure, and the Tribune Building (1873–76;

demolished), an early skyscraper that was the third office building in

the city that incorporated an elevator. In 1882, Hunt designed William

K. Vanderbilt's mansion on Fifth Avenue at Fifty-second Street, an early

example of a mansion designed in direct reference to European historical

precedents. He later designed many city mansions and country estates for

the Vanderbilts and other wealthy New Yorkers. While many of his homes

in Newport and similar summer colonies are extant, few of his city

buildings still stand.

"Richard Morris Hunt provided a

professional model for architects at the end of the 19th century. His

work, bridging the move from High Victorian to formal classicism,

similarly provided models in diverse areas, ranging from apartment

complexes, spacious residences for the wealthy, public libraries,

collaborative works of sculpture and major art museums."

— International Dictionary of Architects

and Architecture : Volume 1, Architects, p418.

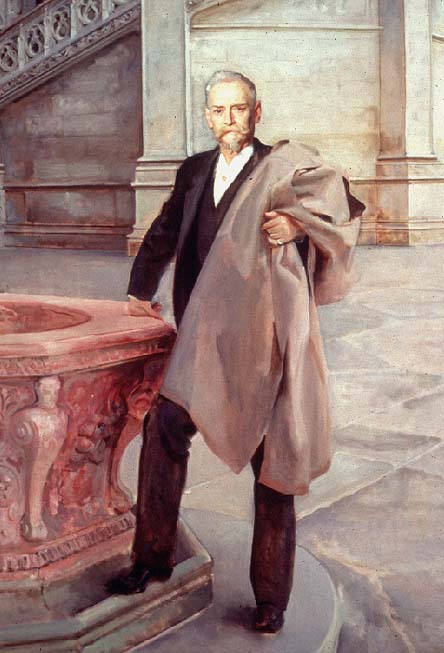

Richard Morris Hunt

1895

Biltmore Estate, near Asheville, North Carolina

Oil on canvas

91 1/2 x 60 in.

Richard Morris Hunt (1828-1895) was an architect who is widely credited as

the one of the fathers of American architecture. He started the first

studio in America to formally train young architects in New York and

took a prominent role in founding the American Institute of Architects,

of which he became president in 1888. Much of his work is eclectic and

designs were borrowed from many European historic styles -- some

derivative of 19th century French traditions of the Beaux-Arts, having

witnessed first hand the stunning transformation of Paris through city

planning and beautification. When he returned to America he became part

of the City Beautiful Movement.

George W. Vanderbilt hired Sargent to paint the renown architect who was

designing his country chateau at Biltmore. When Sargent arrived, the

building's facade was covered with scaffolding, the grounds were nothing

but mud, and hundreds of construction workers were busy working

everywhere. There was no background to paint. The whole place was a

mess. But he was instructed to envision what it might be.

For Sargent, the whole commission was a disaster. Even Hunt's wife was

giving him problems. Insisting that her husband (who was in extremely

poor heath) should be depicted, not as he looked, but as she wanted him

to look.

You can clearly see the painting wasn't working for Sargent. Hunt, as the

central subject, is the least interesting figure of this painting. It

seems Sargent felt more comfortable painting the Venetian well-head than

his central figure.

When Sargent first met Hunt is unknown. They were both alumni of the Ecole

des Beaux-Arts though Hunt had studied there some 25 years prior to

Sargent. It's possible that they ran into each other at Hunt's 10th

Street Studio in New York were John's friend William Merritt Chase also

had a studio.

When John finally painted Hunt, he was at the height of his long career

that spanned four decades.

* * *

Hunt became exposed to the idea of architecture in Europe when his mother

took her family there to visit for a year -- they would stay for more

than a decade.

He entered Hector Martin Lefuel's atelier (a distinguished Parisian

architect and teacher during a significant period of the city's

development) and formally studied between (1843-54). He was the first

native American to study architecture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

Before he left, he won the school’s highest prize -- the Grand Prix de

Rome.

With such an award, government commissions would be easy to come by. In

1854 he was appointed inspector of works on the buildings connecting the

Tuileries with the Louvre. Working under Lefuel, he designed the

Pavillion de la Biblioteque ("Library Pavilion"), opposite the Palais

Royal.

Encouraged to stay in Paris for a promising career, he declined. When his

mother wrote that possibly he should reconsider -- that people were

telling her that the U.S. wasn't ready for the Fine Arts, Hunt replied:

if that is what they think then "there was no place in the world where

they are more needed, or where they should be more encouraged.” He

returned to New York undaunted in 1855 and worked under T. U. Walter on

the extensions of the Capitol at Washington, D.C.

On his own he designed the Lenox library (since torn down). The critic

Montgomery Schuyler at the time pronounced the new library “the most

monumental public building in New York.”

He designed one of the first buildings with an elevator -- the Tribune

building in New York (1873 ). Designed the Theological library, and

Marquand chapel at Princeton; the Devinity college and the Scroll and

Key building at Yale (1869) which were encrusted with trefoils,

fleurs-de-lis, and flying buttresses looking like High Victorian Gothic;

the first building for the Fogg Museum of Art, Cambridge, Mass; and was

chosen, appropriately, for the Yorktown monument, VA. which honored the

French-American victory over the British in the American Revolution.

He was an incredibly hard worker and pushed himself regardless of

persistent poor health. One of the bookplates in his library had the

Latin inscription: “Ars Longa, Vita Brevis Est” -- Art is long, life is

brief.

His greatest achievement was the Administration building at Chicago's

World's Columbian exposition (1893). The building stood (for the men of

the City Beautiful Movement) as the symbolic capital of the White City,

and Hunt received the gold medal from the Institute of British

Architects. Today, his most seen works are probably the Pedestal for the

Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor (dedicated 1886), and the front

facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1890-02).

David Garrard Lowe, in his article in the City Journal called Hunt "the

man who gilded the Gilded Age." Among Hunt's noteworthy buildings were

his opulent residences of the the new moneyed barons on 5th Avenue in

New York City: Henry G Marquand (c. 1875), W. K Vanderbilt (begun 1877),

J.J. Astor (1893); several of the large so called "summer cottages" at

Newport R.I., including William K. Vanderbilt's "Marble House" (1888);

his brother's home "The Breakers" (1893); and of course George W.

Vanderbilt's country chateau at Biltmore (1889-95) where Sargent had

painted him.

Hunt establish a school of learning in his studio modeled after the

ateliers of Paris but he went further demanding rigorous instruction

modeled on the École des Beaux-Arts -- combining both. In his studio he

had a library of more than 5,000 volumes, thousands of photographs of

buildings, and its extensive collection of plaster casts of design

details. With William Merritt Chase teaching in the same building, the

10th street studio quickly became New York's version of a little Paris,

and bright young students came flocking.

Sargent clearly admired Hunt though I'm not sure they ever were more than

just acquaintances. There really wasn't much time since Hunt died later

that same year Sargent painted him.

In the circles of their lives, they shared many mutual friends. Among them

were Henry Marquand and Charles McKim both pallbearers at Hunt's funeral

at Trinity Church, Newport, RI. It was McKim that had publicly

recognized the W. K Vanderbilt Fifth Avenue château (1877-1881) as the

first complete expression of the Beaux-Arts style in America. Hunt was

buried in Newport’s Island Cemetery and on his gravestone is the line

from another of his bookplates: “Laborare Est Orare” -- Labor is

prayer.

It seemed to fit.

It also seemed to fit Sargent, for it would be this exact Latin phrase

that John would request and is inscribed on his own gravestone.

Special thanks to

http://www.jssgallery.org

Richard Morris Hunt (1827-1895) was from a wealthy colonial family who

moved to Paris in 1843. He studied architecture, painting, and sculpture

at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He traveled widely throughout

Europe and was made an assistant at the Ecole in 1854. He took his

knowledge French Renaissance Revival back to New York in 1855. He

returned to Europe twice in the 1860's and finally settled in the

States.

In 1873 he built the Tribune Building in New York, an early skyscraper. He

also did many summer homes for aristocrats such as the Vanderbilts and

J.J. Astor. French Renaissance remained his favorite style. He

contributed the Administration Building to the Chicago Exposition of

1893. He was one of the founders of the American Institute of

Architects.

|

Richard Morris Hunt's George W.

Vanderbilt's Biltmore

George W. Vanderbilt's

Biltmore, N. C. 1889-95

Richard Morris Hunt, architect

Frederick Law Olmsted landscape architect Jpg:

Net

From

www.biltmore.com

:

George Vanderbilt

engaged two of the most distinguished designers of the

19th century: architect Richard Morris Hunt (1828-95)

and landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903)

to create a little bit of Eden on some 8,000 acre

estate.

Hunt modeled the

architecture on the richly ornamented style of the

French Renaissance and adapted elements, such as the

stair tower and the steeply pitched roof, from three

famous early-16th-century châteaux in the Loire Valley:

Blois, Chenonceau, and Chambord.

Boasting 4 acres of

floor space, the 250-room mansion featured 34 master

bedrooms, 43 bathrooms, 65 fireplaces, 3 kitchens, and

an indoor swimming pool. Priceless art works and

furnishings adorned its interiors. The surrounding

grounds were equally impressive, encompassing 125,000

acres of forest, park, and gardens.

Notwithstanding its

grandeur, Biltmore Estate was very much a home. It was

here that George pursued his interests in art,

literature, and horticulture, and also started a family.

He married American socialite

Edith Stuyvesant Dresser (1873-1958) in June 1898 in

Paris, and the couple came to live at the Estate that

fall after honeymooning in Europe. Their only child,

Cornelia (1900-1976), was born and grew up at Biltmore.

It took six years to

build it and in December of 1895, at his grand opening

party, it was still unfinished (taking 3 additional

years to complete).

(http://www.biltmore.com/visit/estate_history/index.html)

Stair Tower

steeply pitched roof

Interior

Arial view of estate

Olmsted & Hunt's Biltmore at

Autumn

Winter (stunning)

Winter closer view

Gardens

|

|