|

New York

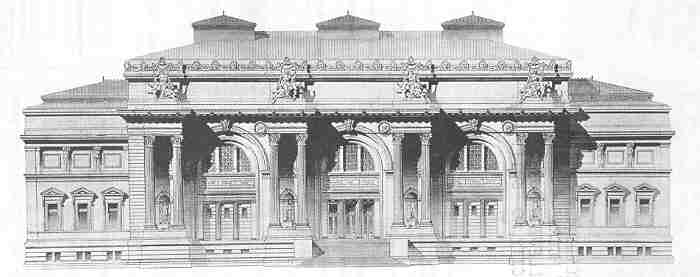

Architecture Images-Upper East Side Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|

architect |

1880- original portion (now

mostly covered by additions) Calvert

Vaux

and Jacob Wrey Mould, 1902-Richard Morris Hunt designed the central pavilion and the neoclassical facade 1911-McKim, Mead and White designed the north and south wings since 1975 - Six additional wings, designed by the architectural firm of Roche Dinkeloo major wings by Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould, 1870-80; Thomas Weston with Arthur L. Tuckerman, associate, 1883-88; Arthur L. Tuckerman, 1890-94; Richard Morris Hunt, 1894-95; Richard Howland Hunt and George B. Post, 1895-1902; McKim, Mead & White, 1904-26; Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo Associates, 1967-90 |

|

location |

5th Avenue at 82nd St. |

|

date |

1880 |

|

style |

Neoclassical |

|

construction |

stone |

|

type |

Museum |

|

|

.jpg)  |

|

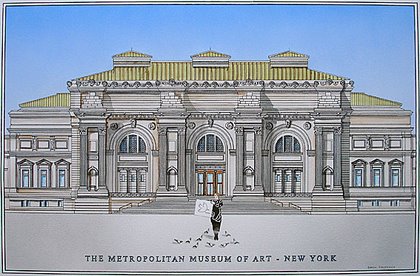

| Rendering copyright Simon Fieldhouse. Click here for a Simon Fieldhouse gallery. | |

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE MUSEUM

|

|

|

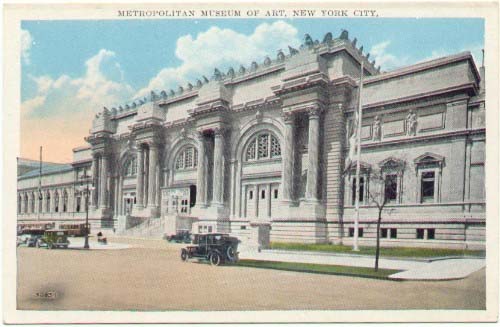

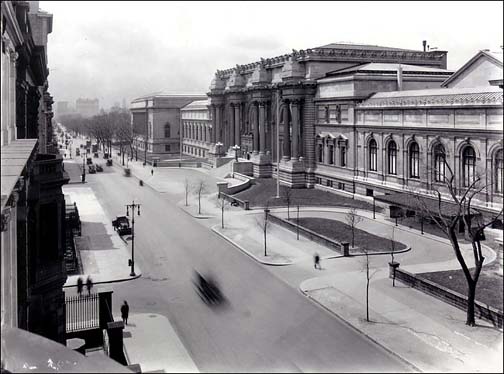

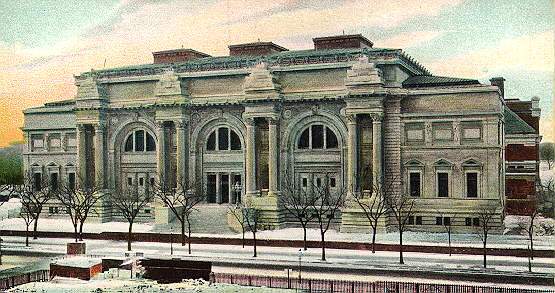

STREETSCAPES/The Metropolitan Museum's

Facade; The Many Faces Of a Grand Monument By CHRISTOPHER GRAY Published: February 13, 2005, Sunday IN the right winter light it is soft and glowing, almost like alabaster. But it is Indiana limestone, and the ongoing cleaning of the great, sweeping main facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art is transforming the museum's north and south wings from grand classical-style monuments into something personal, even poetic. The museum's first buildings in Central Park were set back from Fifth Avenue and shared the appearance of structures set within a park, apart from the city. But in 1902, the museum finished its central entrance at Fifth Avenue and 82nd Street, designed in 1895 by Richard Morris Hunt just before his death. The new section, with its rich Beaux-Arts front, face to face with the grid of New York, brought the Metropolitan into the fabric of the city. (Hunt had wanted a luminous marble for the facade, but the trustees could afford only limestone.) In 1904, the trustees hired McKim, Mead & White to design a comprehensive development. The firm's early designs for the museum are slightly terrifying -- they would have expanded the Met into a vast, long, low building on the scale of structures in Washington or even larger. On the west front, facing Central Park, the architects envisioned a great formal terrace reaching beyond the park's present east drive, and at the north and south ends, they designed colossal formal plazas and facades, resembling the temple-fronted Brooklyn Museum of the 1890's. But even for the Met this plan went too far, and McKim, Mead & White's proposals were gradually scaled back until almost nothing of its design for the south, west and north facades was built. The trustees proceeded with four wings facing Fifth Avenue, two to the north and two to the south of the original structure. The four wings were completed in two stages, first heading north to the 84th Street transverse (finished by 1913) and then going south, to 80th Street (finished by 1926). The basic design is chaste but hardly memorable, set out by Charles McKim, the firm's subdued classicist, who died in 1909. William Mead made cost-cutting changes the year McKim died, gaining a bit more room by eliminating the space behind what had been planned as freestanding columns like those on the 1902 entrance. The last two sections -- south of the 1902 wing -- are slightly simpler than the earlier two to the north, but that distinction is lost to the typical visitor, who now sees a Pentagon-like sweep of stone 1,000 feet long. McKim, Mead & White obviously sought a majesty for the wings, tempered with deference to the 1902 structure, and one way the firm got it was to set the later facades off from the street behind a retaining wall and a plot of grass. Except for a small auditorium entrance opposite 83rd Street, all attention was funneled to the main staircase. (The renowned firm's other designs over the years included Pennsylvania Station, the Morgan Library and the Boston Public Library.) By the 1940's, the Met's trustees had begun to see the grand entrance as a bottleneck. They considered replacing the stair with a vehicular ramp, and also simply leaving a straightforward ground-floor entrance, as had been done at the Brooklyn Museum in the 1930's, when its staircase was removed. In the 1950's, the Met trustees revisited the issue, examining a design to replace the grand stair with a grade-level entrance, presenting the visitor with a bank of escalators just inside the new doorway up to the great hall. But little happened until 1967, when Thomas P.F. Hoving arrived as the museum's president. Mr. Hoving retained the architects Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo & Associates to develop a plan for the museum that became almost as expansive as McKim, Mead & White's conception. The new design engulfed the irregular south, west and north wings in a severe sheath of limestone and glass, including the wing housing the Temple of Dendur on the 84th Street side. On Fifth Avenue, the intervention was more complicated. New blockbuster exhibitions were bringing new crowds, and the steps that were grand in 1902 were, on occasion in the 1960's, dangerously crowded. Mr. Hoving and the architects expanded the steps forward and to the sides, and added two wide landings. At the same time, they eliminated the grass plots in front of the McKim, Mead & White wings. At the extreme north and south ends, new groves of trees and benches created a sort of public gathering space, where vendors and passers-by take the shade. On either side of the new entrance, bare, open areas have fountains with comfortable-looking rims -- but the water level is kept just high enough to discourage sitting on the edges. The landscape looks persuasive on paper but is uninviting to loiterers -- presumably by design. This single super-plaza was said to have unified the museum's front -- as if the front left by Richard Morris Hunt and McKim, Mead & White was somehow defective. McKim, Mead & White's forgettable limestone facades had derived grandeur when set down on grass -- but lost it when set down on 1970's-style plaza pavers. The original 1902 entrance definitely came out a loser. The 1,000-foot-long plaza denatures the entrance's basic vertical character; the spreading staircase destroys the tart separateness of the twin-column bases; and the plaza paving is a much less friendly contrast against the limestone wings than was the grass. Writing in Artforum in 1970, the critic and historian Bernhard Leitner lamented ''the obtrusive dictatorship of the new scale'' and called the result the ''Metropolitan Bank of Art.'' Still, a wanderer in the art gallery that is the city's streets cannot be too picky, and the Fifth Avenue front does reward the art lover willing to pause before entering. There is the sweep of classical-style detailing, almost as long as the World Trade Center was tall. Then there is the interplay between the museum's facade and the surviving mansions, especially those of the Marymount School at 84th Street. Finally, there is the stone itself, especially on the northernmost wing. Since its cleaning late last year, it has seemed like several different materials: sometimes like ice cream, under the nighttime illumination; sometimes translucent yellowy-pink, in raking light; sometimes sparkling in the low winter sun, like a back-country field of fresh-fallen snow. Published: 02 - 13 - 2005 , Late Edition - Final , Section 11 , Column 4 , Page 12 Copyright New York Times |

|

|

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, often referred to simply as "the Met", is

one of the world's largest and most important art museums. The main

building is located on the eastern edge of Central Park in New York

City, New York, United States, along what is known as Museum Mile. It

was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986. The Met has a much

smaller second location at "The Cloisters," featuring medieval art. Overview The Met's permanent collection contains more than two million works of art, divided into nineteen curatorial departments.[4] Represented in the permanent collection are works of art from classical antiquity and Ancient Egypt, paintings and sculptures from nearly all the European masters, and an extensive collection of American and modern art. The Met also maintains extensive holdings of African, Asian, Oceanic, Byzantine and Islamic art.[5] The museum is also home to encyclopedic collections of musical instruments, costumes and accessories, and antique weapons and armor from around the world.[6] A number of notable interiors, ranging from 1st century Rome through modern American design, are permanently installed in the Met's galleries.[7] In addition to its permanent exhibitions, the Met organizes and hosts large travelling shows throughout the year.[8] History Opening reception in the picture gallery at 681 Fifth Avenue, February 20, 1872. Wood engraving published in Frank Leslie's Weekly, March 9, 1872. The central lobby of the museumThe Metropolitan Museum of Art first opened on February 20, 1872, housed in a building located at 681 Fifth Avenue in New York City. John Taylor Johnston, a railroad executive whose personal art collection seeded the museum, served as its first President, and the publisher George Palmer Putnam came on board as its founding Superintendent. Under their guidance, the Met's holdings, initially consisting of a Roman stone sarcophagus and 174 mostly European paintings, quickly outgrew the available space. In 1873, occasioned by the Met's purchase of the Cesnola Collection of Cypriot antiquities, the museum decamped from Fifth Avenue and took up residence at the Douglas Mansion on West 14th Street. However, these new accommodations were temporary; after negotiations with the city of New York, the Met acquired land on the east side of Central Park, where it built its permanent home, a red-brick Gothic Revival stone "mausoleum" designed by American architects Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould.[9] The Met has remained in this location ever since, and the original structure is still part of its current building. A host of additions over the years, including the distinctive Beaux-Arts facade, designed by Richard Morris Hunt and completed in 1926, have continued to expand the museum's physical structure. As of 2007, the Met measures almost a quarter mile long and occupies more than two million square feet, more than 20 times the size of the original 1880 building.[10] Directors Its director from 1955 to his death on May 11, 1966, was James J. Rorimer. He was succeeded by Thomas Hoving, who served from March 17, 1967 to June 30, 1977. The current director is Philippe de Montebello, who announced January 8, 2007 that he planned to retire at the end of the year.[11] Departments The Met's permanent collection is cared for and exhibited by nineteen separate departments, each with a specialized staff of curators, restorers, and scholars. American Decorative Arts The American Decorative Arts Department includes about 12,000 examples of American decorative art, ranging from the late seventeenth to the early twentieth century. Though the Met acquired its first major holdings of American decorative arts via a 1909 donation by Margaret Olivia Slocum Sage, wife of the financier Russell Sage, a decorative arts department specifically dedicated to American works was not established until 1934. One of the prizes of the American Decorative Arts department is its extensive collection of American stained glass. This collection, probably the most comprehensive in the world, includes many pieces by Louis Comfort Tiffany. The department is also well-known for its twenty-five period rooms, each of which recreates an entire room, furnishings and all, from a noted period or designer. The department's current holdings also include an extensive silver collection notable for containing numerous pieces by Paul Revere as well as works by Tiffany & Co. American Paintings and Sculpture Ever since its founding, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has placed a particular emphasis on collecting American art. The first piece to enter the Met's collection was an allegorical sculpture by Hiram Powers titled California, acquired in 1870, which can still be seen in the Met's galleries today. In the following decades, the Met's collection of American paintings and sculpture has grown to include more than one thousand paintings, six hundred sculptures, and 2,600 drawings, covering the entire range of American art from the early Colonial period through the early twentieth century. Many of the best-known American paintings are held in the Met's collection, including a portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart and Emanuel Leutze's monumental Washington Crossing the Delaware. The collection also includes masterpieces by such notable American painters as Winslow Homer, George Caleb Bingham, John Singer Sargent, James McNeill Whistler, and Thomas Eakins. Ancient Near Eastern Art 7th millennium BC anthropomorphized rocks found in modern-day IsraelBeginning in the late 1800s, the Met started to acquire ancient art and artifacts from the Near East. From a few cuneiform tablets and seals, the Met's collection of Near Eastern art has grown to more than 7,000 pieces. Representing a history of the region beginning in the Neolithic Period and encompassing the fall of the Sassanian Empire and the end of Late Antiquity, the collection includes works from the Sumerian, Hittite, Sassanian, Assyrian, Babylonian and Elamite cultures (among others), as well as an extensive collection of unique Bronze Age objects. The highlights of the collection include a set of monumental stone lammasu, or guardian figures, from the Northwest Palace of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II. Arms and Armor The Met's Department of Arms and Armor is one of the museum's most popular collections. The distinctive "parade" of armored figures on horseback installed in the first-floor Arms and Armor gallery is one of the most recognizable images of the museum. The department's focus on "outstanding craftsmanship and decoration", including pieces intended solely for display, means that the collection is strongest in late medieval European pieces and Japanese pieces from the fifth through the nineteenth centuries. However, these are not the only cultures represented in Arms and Armor; in fact, the collection spans more geographic regions than almost any other department, including weapons and armor from dynastic Egypt, ancient Greece, the Roman Empire, the ancient Near East, Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, as well as American firearms (especially Colt firearms) from the nineteenth and 20th centuries. Among the collection's 15,000 objects are many pieces made for and used by kings and princes, including armor belonging to Henry II of France and Ferdinand I of Germany. Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas Though the Met first acquired a group of Peruvian antiquities in 1882, the museum did not begin a concerted effort to collect works from Africa, Oceania, and the Americas until 1969, when American businessman and philanthropist Nelson A. Rockefeller donated his more than 3,000-piece collection to the museum. Today, the Met's collection contains more than 11,000 pieces from sub-Saharan Africa, the Pacific Islands and the Americas and is housed in the 40,000-square-foot (4,000 m²) Rockefeller Wing on the south end of the museum. The collection ranges from 40,000-year-old Australian Aboriginal rock paintings, to a group of fifteen-foot high memorial poles carved by the Asmat people of New Guinea, to a priceless collection of ceremonial and personal objects from the Nigerian Court of Benin. The range of materials represented in the Africa, Oceania, and Americas collection is undoubtedly the widest of any department at the Met, including everything from precious metals to porcupine quills. Asian Art Hokusai's The Great Wave off KanagawaThe Met's Asian department holds a collection of Asian art that is arguably the most comprehensive in the West. The collection dates back almost to the founding of the museum: many of the philanthropists who made the earliest gifts to the museum included Asian art in their collections. Today, an entire wing of the museum is dedicated to the Asian collection, which contains more than 60,000 pieces and spans 4,000 years of Asian art. Every Asian civilization is represented in the Met's Asian department, and the pieces on display include every type of decorative art, from painting and printmaking to sculpture and metalworking. The department is well-known for its comprehensive collection of Chinese calligraphy and painting, as well as for its Nepalese and Tibetan works. However, not only "art" and ritual objects are represented in the collection; many of the best-known pieces are functional objects. The Asian wing even contains a complete Ming Dynasty garden court, modeled on a courtyard in the Garden of the Master of the Fishing Nets in Suzhou. The Costume Institute In 1937, the Museum of Costume Art joined with the Met and became its Costume Institute department. Today, its collection contains more than 80,000 costumes and accessories. Due to the fragile nature of the items in the collection, the Costume Institute does not maintain a permanent installation. Instead, every year it holds two separate shows in the Met's galleries using costumes from its collection, with each show centering on a specific designer or theme. In past years, Costume Institute shows organized around famous designers such as Chanel and Gianni Versace have drawn significant crowds to the Met. The Costume Institute's annual Benefit Gala, co-chaired by Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour, is an extremely popular, if exclusive, event in the fashion world; in 2007, the 700 available tickets started at $6,500 per person.[12] Drawings and Prints Though other departments contain significant numbers of drawings and prints, the Drawings and Prints department specifically concentrates on North American pieces and western European works produced after the Middle Ages. Currently, the Drawings and Prints collection contains more than 11,000 drawings, 1.5 million prints, and twelve thousand illustrated books. The collection has been steadily growing ever since the first bequest of 670 drawings donated to the museum by Cornelius Vanderbilt in 1880. The great masters of European painting, who produced many more sketches and drawings than actual paintings, are extensively represented in the Drawing and Prints collection. The department's holdings contain major drawings by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Rembrandt, as well as prints and etchings by Van Dyck, Dürer, and Degas among many others. Egyptian Art A view of the Sackler Wing's enclosed courtyard, with the reassembled temple of Dendur in the background. Another view of the temple of Dendur.Though the majority of the Met's initial holdings of Egyptian art came from private collections, items uncovered during the museum's own archeological excavations, carried out between 1906 and 1941, constitute almost half of the current collection. More than 36,000 separate pieces of Egyptian art from the Paleolithic era through the Roman era constitute the Met's Egyptian collection, and almost all of them are on display in the museum's massive wing of 40 Egyptian galleries. Among the most valuable pieces in the Met's Egyptian collection are a set of 24 wooden models, discovered in a tomb in Deir el-Bahri in 1920. These models depict, in unparalleled detail, a veritable cross-section of Egyptian life in the early Middle Kingdom : boats, gardens, and scenes of daily life. However, the popular centerpiece of the Egyptian Art department continues to be the Temple of Dendur. Dismantled by the Egyptian government to save it from rising waters caused by the building of the Aswan High Dam, the large sandstone temple was given to the United States in 1965 and assembled in the Met's Sackler Wing in 1978. Situated in a large room, partially surrounded by a reflecting pool and illuminated by a wall of windows opening onto Central Park, the Temple of Dendur is one of the Met's most enduring attractions. European Paintings Velázquez's Juan de ParejaThe Met has one of the world's best collections of European paintings. Though the collection numbers only around 2,200 pieces, it contains many of the world's most instantly recognizable paintings. The bulk of the Met's purchasing has always been in this department, primarily focusing on Old Masters and nineteenth-century European paintings, with an emphasis on French, Italian and Dutch artists. Many great artists are represented in remarkable depth in the Met's holdings: the museum owns thirty-seven paintings by Monet, twenty-one oils by Cezanne, and eighteen Rembrandts including Aristotle With a Bust of Homer. The Met's five paintings by Vermeer represent the largest collection of the artist's work anywhere in the world. Other highlights of the collection include Van Gogh's Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat, Pieter Bruegel the Elder's The Harvesters, Georges de La Tour's The Fortune Teller, and Jacques-Louis David's The Death of Socrates. In recent decades, the Met has carried out a policy of deaccessioning its "minor" holdings in order to purchase a smaller number of "world-class" pieces. Though this policy remains controversial, it has gained a number of outstanding (and outstandingly expensive) masterpieces for the European Paintings collection, beginning with Velázquez's Juan de Pareja in 1971. One of The Met's latest purchases is Duccio's Madonna and Child, which cost the museum more than 45 million dollars, more than twice the amount it had paid for any previous painting. The painting itself is only slightly larger than 9 by 6 inches, but has been called "the Met's Mona Lisa". European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Though European painting may have its own department, other European decorative arts are well-represented at the Met. In fact, the European Sculpture and Decorative Arts collection is one of the largest departments at the Met, holding in excess of 50,000 separate pieces from the 1400s through the early twentieth century. Though the collection is particularly concentrated in Renaissance sculpture -- much of which can be seen in situ surrounded by contemporary furnishings and decoration -- it also contains comprehensive holdings of furniture, jewelry, glass and ceramic pieces, tapestries, textiles, and timepieces and mathematical instruments. Visitors can enter dozens of completely furnished period rooms, transplanted in their entirety into the Met's galleries. The collection even includes an entire sixteenth-century patio from the Spanish castle of Vélez Blanco, meticulously reconstructed in a two-story gallery. Sculptural highlights of the sprawling department include Bernini's Bacchanal, a cast of Rodin's The Burghers of Calais, and several unique pieces by Houdon, including his Bust of Voltaire and his famous portrait of his daughter Sabine. Greek and Roman Art The Met's collection of Greek and Roman art contains more than 35,000[13] works dated through A.D. 312. The Greek and Roman collection dates back to the founding of the museum -- in fact, the museum's first accessioned object was a Roman sarcophagus, still currently on display. Though the collection naturally concentrates on items from ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, these historical regions represent a wide range of cultures and artistic styles, from classic Greek black-figure and red-figure vases to carved Roman tunic pins. Several highlights of the collection include the Euphronios krater depicting the death of Sarpedon (whose ownership has since been transferred to the Republic of Italy), the monumental Amathus sarcophagus, and a magnificently detailed Etruscan chariot known as the "Monteleone chariot". The collection also contains many pieces from far earlier than the Greek or Roman empires -- among the most remarkable are a collection of early Cycladic sculptures from the mid-third millennium BCE, many so abstract as to seem almost modern. The Greek and Roman galleries also contain several large classical wall paintings and reliefs from different periods, including an entire reconstructed bedroom from a noble villa in Boscoreale, excavated after its entombment by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79. In 2007, the Met's Greek and Roman galleries were expanded to approximately 60,000 square feet (6,000 m²), allowing the majority of the collection to be on permanent display.[14] Islamic Art The Met's collection of Islamic art is not confined strictly to religious art, though a significant number of the objects in the Islamic collection were originally created for religious use or as decorative elements in mosques. Much of the 12,000 strong collection consists of secular items, including ceramics and textiles, from Islamic cultures ranging from Spain to North Africa to Central Asia. In fact, the Islamic Art department's collection of miniature paintings from Iran and Mughal India are a highlight of the collection. Calligraphy both religious and secular is well-represented in the Islamic Art department, from the official decrees of Suleiman the Magnificent to a number of Qur'an manuscripts reflecting different periods and styles of calligraphy. As with many other departments at the Met, the Islamic Art galleries contain many interior pieces, including the entire reconstructed Nur Al-Din Room from an early 18th century house in Damascus. The Islamic Arts galleries are undergoing expansion and are projected to be closed until early 2008. Until that time, a number of items from the collection are on temporary display throughout the museum. Robert Lehman Collection On the passing of banker Robert Lehman in 1969, his Foundation donated close to 3,000 works of art to the museum. Housed in the "Robert Lehman Wing," the museum refers to the collection as "one of the most extraordinary private art collections ever assembled in the United States".[15] To emphasize the personal nature of the Robert Lehman Collection, the Met housed the collection in a special set of galleries which evoked the interior of Lehman's richly decorated townhouse; this intentional separation of the Collection as a "museum within the museum" met with mixed criticism and approval at the time, though the acquisition of the collection was seen as a coup for the Met.[16] Unlike other departments at the Met, the Robert Lehman collection does not concentrate on a specific style or period of art; rather, it reflects Lehman's personal interests. Lehman the collector concentrated heavily on paintings of the Italian Renaissance, particularly the Senese school. Paintings in the collection include masterpieces by Botticelli and Domenico Veneziano, as well as works by a significant number of Spanish painters, El Greco and Goya among them. Lehman's collection of drawings by the Old Masters, featuring works by Rembrandt and Dürer, is particularly valuable for its breadth and quality.[17] Princeton University Press has documented the massive collection in a multi-volume book series published as "The Robert Lehman Collection Catalogues." The Libraries The main library at the Met is the Thomas J. Watson Library, named after its benefactor. The Watson Library primarily collects books related to the history of art, including exhibition catalogues and auction sale publications, and generally attempts to reflect the emphasis of the museum's permanent collection. Several of the museum's departments have their own specialized libraries relating to their area of expertise. The Watson Library and the individual departments' libraries also hold substantial examples of early or historically important books which are works of art in their own right. Among these are books by Dürer and Athanasius Kircher, as well as editions of the seminal Surrealist magazine "VVV" and a copy of "Le Description de l'Egypte," commissioned in 1803 by Napoleon Bonaparte and considered one of the greatest achievements of French publishing. Several of the departmental libraries are open to members of the public without prior appointment. The Library and Teacher Resource Center, Ruth and Harold Uris Center for Education, is open to visitors of all ages to study art and art history and to learn about the Museum, its exhibitions and permanent collection. The Robert Goldwater Library in the department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas documents the visual arts of sub-Saharan Africa, the Pacific Islands, and Native and Precolumbian America. It is open to adult researchers, including college and graduate students. Most of the other departmental libraries are for museum staff only or are open to the general public by appointment only. Medieval Art The Met's collection of medieval art consists of a comprehensive range of Western art from the 4th century through the early 16th century, as well as Byzantine and pre-medieval European antiquities not included in the ancient Greek and Roman collection. Like the Islamic collection, the Medieval collection contains a broad range of two- and three-dimensional art, with religious objects heavily represented. In total, the Medieval Art department's permanent collection numbers about 11,000 separate objects, divided between the main museum building on Fifth Avenue and The Cloisters. Main Building The medieval collection in the main Metropolitan building, centered on the first-floor medieval gallery, contains about six thousand separate objects. While a great deal of European medieval art is on display in these galleries, most of the European pieces are concentrated at the Cloisters (see below). However, this allows the main galleries to display much of the Met's Byzantine art side-by-side with European pieces. The main gallery is host to a wide range of tapestries and church and funerary statuary, while side galleries display smaller works of precious metals and ivory, including reliquary pieces and secular items. The main gallery, with its high arched ceiling, also serves double duty as the annual site of the Met's elaborately decorated Christmas tree. The Cloisters The Cloisters was a principal project of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who was a major benefactor of the Met. Located in Fort Tryon Park and completed in 1938, it is a separate building dedicated solely to medieval art. The Cloisters collection was originally that of a separate museum, assembled by George Grey Barnard and acquired in toto by Rockefeller in 1925 as a gift to the Met.[18] The Cloisters are so named on account of the five medieval French cloisters whose salvaged structures were incorporated into the modern building, and the five thousand objects at the Cloisters are strictly limited to medieval European works. The collection exhibited here features many items of outstanding beauty and historical importance; among these are the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry illustrated by the Limbourg Brothers in 1409, the Romanesque altar cross known as the "Cloisters Cross" or "Bury Cross," and the seven heroically detailed tapestries depicting the Hunt of the Unicorn. Modern Art With more than 10,000 artworks, primarily by European and American artists, the modern art collection occupies 60,000 square feet (6,000 m²), of gallery space and contains many iconic modern works. Cornerstones of the collection include Picasso's portrait of Gertrude Stein, Jasper Johns's White Flag, Jackson Pollock's Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), and Max Beckmann's triptych Beginning. Certain artists are represented in remarkable depth, for a museum whose focus is not exclusively on modern art: for example, the collection contains forty paintings by Paul Klee, spanning his entire career. Due to the Met's long history, "contemporary" paintings acquired in years past have often migrated to other collections at the museum, particularly to the American and European Paintings departments. Musical Instruments The Met's collection of musical instruments, with about five thousand examples of musical instruments from all over the world, is virtually unique among major museums. The collection began in 1889 with a donation of several hundred instruments by Lucy W. Drexel, but the department's current focus came through donations over the following years by Mary Elizabeth Adams, wife of John Crosby Brown. Instruments were (and continue to be) included in the collection not only on aesthetic grounds, but also insofar as they embodied technical and social aspects of their cultures of origin. The modern Musical Instruments collection is encyclopedic in scope; every continent is represented at virtually every stage of its musical life. Highlights of the department's collection include several Stradivari violins, a collection of Asian instruments made from precious metals, and the oldest surviving piano, a 1720 model by Bartolomeo Cristofori. Many of the instruments in the collection are playable, and the department encourages their use by holding concerts and demonstrations by guest musicians. Photographs Steichen's The Pond-MoonlightThe Met's collection of photographs, numbering more than 20,000 in total, is centered on five major collections plus additional acquisitions by the museum. Alfred Stieglitz, a famous photographer himself, donated the first major collection of photographs to the museum, which included a comprehensive survey of Photo-Secessionist works, a rich set of master prints by Edward Steichen, and an outstanding collection of Stieglitz's photographs from his own studio. The Met supplemented Stieglitz's gift with the 8,500-piece Gilman Paper Company Collection, the Rubel Collection, and the Ford Motor Company Collection, which respectively provided the collection with early French and American photography, early British photography, and post-WWI American and European photography. The museum also acquired Walker Evans's personal collection of photographs, a particular coup considering the high demand for his works. Though the department gained a permanent gallery in 1997, not all of the department's holdings are on display at any given time, due to the sensitive materials represented in the photography collection. However, the Photographs department has produced some of the best-received temporary exhibits in the Met's recent past, including a Diane Arbus retrospective and an extensive show devoted to spirit photography. Special Exhibitions Frank Stella on the Roof features in stainless steel and carbon fiber several works by American artist Frank Stella. This exhibition is set in The Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden, offering views of Central Park and the Manhattan skyline. Coaxing the Spirits to Dance: Art of the Papuan Gulf presents some 60 sculptures and 30 historical photographs from the Gulf province of Papua New Guinea. Acquisitions and Deaccessioning at the Met Inside the Metropolitan Museum of ArtDuring the 1970s, under the directorship of Thomas Hoving, the Met revised its deaccessioning policy. Under the new policy, the Met set its sights on acquiring "world-class" pieces, regularly funding the purchases by selling mid- to high-value items from its collection.[19] Though the Met had always sold duplicate or minor items from its collection to fund the acquisition of new pieces, the Met's new policy was significantly more aggressive and wide-ranging than before, and allowed the deaccessioning of items with higher values which would normally have precluded their sale. The new policy provoked a great deal of criticism (in particular, from the New York Times). However, the new policy had its intended effect; many of the items then purchased with funds generated by the more liberal deaccessioning policy are now considered the "stars" of the Met's collection, including Velasquez's Juan de Pareja and the Euphronios krater depicting the death of Sarpedon. In the years since the Met began its new deaccessioning policy, other museums have begun to emulate it with aggressive deaccessioning programs of their own.[20] The Met has continued the policy in recent years, selling such valuable pieces as Edward Steichen's 1904 photograph The Pond-Moonlight (of which another copy was already in the Met's collection) for a record price of $2.9 million.[21] In Popular Culture The Met was famously used as the setting for much of the Newbery Medal-winning children's book, From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, in which the two young protagonists run away from home and secretly stay several nights in the museum. However, Michelangelo's Angel statue, central to the book's plot, is purely fictional and not actually part of the museum's collection. The main characters of the CW's Gossip Girl TV series usually hang out on the steps of the met. The Met was featured as the first level in the tactical first-person shooter Tom Clancy's Rainbow Six: Rogue Spear The 1999 version of The Thomas Crown Affair uses the Met as a major setting; however, only the exterior scenes were shot at the museum, with the interior scenes filmed on soundstages. In 1983, there was a Sesame Street special entitled Don't Eat the Pictures: Sesame Street at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the cast goes to visit the museum on-location. An episode of Inspector Gadget entitled "Art Heist" had Gadget and Penny and Brain travel to the Met, with Gadget being assigned to protect the artwork. But M.A.D. Agents steal the masterpieces and plan to replace them with fakes. |

|

|

links |

|