|

New York Architecture Images- Gone

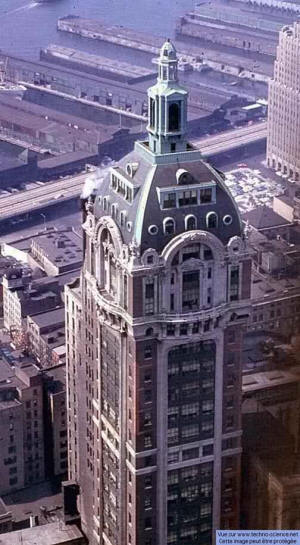

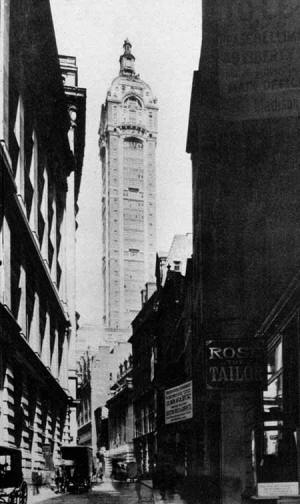

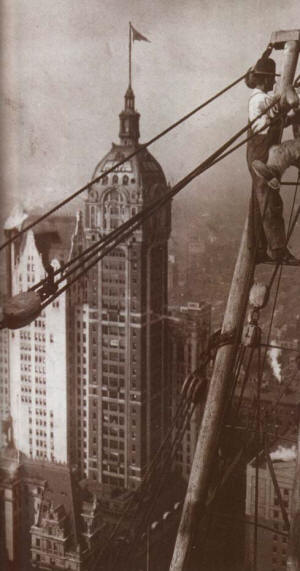

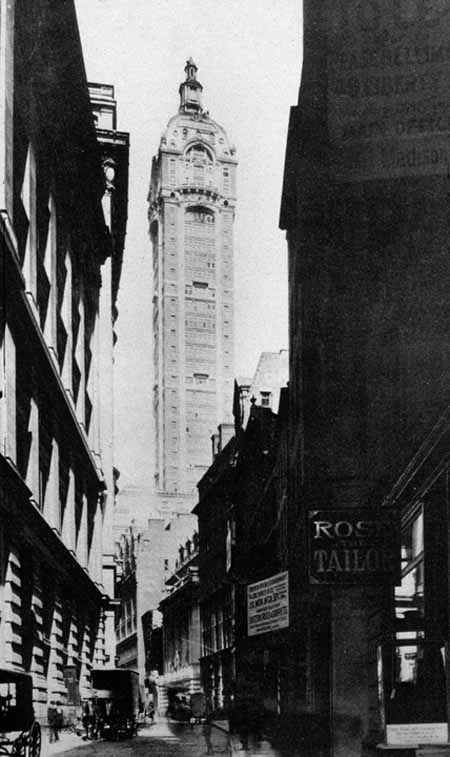

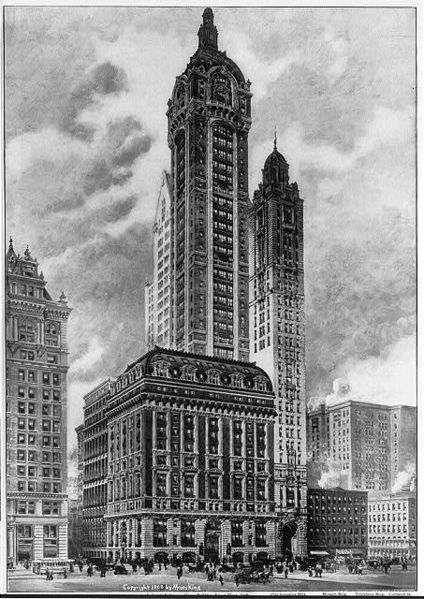

Singer Building |

||||||||||||

|

architect |

Ernest Flagg | ||||||||||||

|

location |

Broadway and Liberty Street | ||||||||||||

|

date |

1906-1908, demolished 1968. | ||||||||||||

|

style |

Second Empire Baroque | ||||||||||||

|

construction |

steel frame, limestone trim, red brick | ||||||||||||

|

type |

Office Building | ||||||||||||

| Click here for Singer Building gallery | |||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

images |

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

notes |

Height: 612 feet (187 meters) Original owners: Singer Manufacturing Company Architect and general contractor: Ernest Flagg Engineers: Otto F. Semsch; Boller & Hodge, Charles G. Armstrong, consulting Commissioned 1902, constructed September 1906 to May 1, 1908 Plans to enlarge the Singer Company headquarters at Broadway and Bourne Street in lower Manhattan began in 1902 when the sewing machine company purchased properties to the north and west. The first design by architect Ernest Flagg was a thirty-five story tower, but the company soon decided to nearly double that height with a tower of almost 600 feet. Completed in 1908, just twenty months after the foundations were set, the Beaux-Arts style tower of red brick and bluestone stretched to 612 feet, besting the Park Row Building by 226 feet. Chief engineer Otto F. Semsch tackled the problem of windbracing for the slender tower and the construction of the costly caisson foundations. Although significantly taller than previous skyscrapers, the Singer Tower held the title for only a year, when it was surpassed by the Metropolitan Life Tower. In 1963 the Singer Corporation sold the building, and in 1968 it became the tallest building ever demolished as it made way for the U.S. Steel Building (now known as 1 Liberty Plaza). Text by Melissa Matlins |

||||||||||||

|

January 2, 2005 STREETSCAPES Once the Tallest Building, But Since 1967 a Ghost By CHRISTOPHER GRAY A WELL-KNOWN TOWER The Singer Building as it looked when demolition began in 1967, with a wall decoration in the lobby that used needle and thread imagery. The building was one of several designed by the visionary architect Ernest Flagg for Frederick Bourne. The 41-story Singer Building, the tallest in the world in 1908 when it was completed at Broadway and Liberty Street, was until Sept. 11, 2001, the tallest structure ever to be demolished. The building, an elegant Beaux-Arts tower, was one of the most painful losses of the early preservation movement when it was razed in 1967. A Manhattan reader, Robert Bittencourt, wondered why such an iconic building was removed from the city's streetscape. The answer: size matters. The building was the result of an unusual patron-architect partnership between Frederick Bourne, the head of the Singer Sewing Machine Company, and Ernest Flagg, a visionary architect who at first opposed skyscrapers. Around 1880, Bourne was an industrious clerk in the Mercantile Library when he somehow earned the admiration of Alfred Corning Clark, the son of Edward Clark. The elder Clark was at the time the head of Singer, and was also starting to build his Dakota apartment house at 72nd Street and Central Park West. Bourne began working for the Clarks - indeed, a 1905 account in The New York Press said that Bourne had directed the construction of the Dakota. Bourne was soon brought into the Singer company, which was selling 500,000 sewing machines a year; he became its president in 1889. In 1896, Bourne hired the Paris-trained Flagg, an early exponent of the Beaux-Arts style, to design a new Singer headquarters at Broadway and Liberty Street. Flagg's original red brick and stone structure, with its mansard roof, was an assured but not remarkable Paris-style building. In 1902 Bourne had Flagg design a loft building for the company at 561 Broadway, near Prince Street - an ingenious and sophisticated mix of frankly exposed structural terra cotta, steel and ironwork, with whimsical red and green coloring. In the same year, Bourne began acquiring additional land for a far more important architectural commission for Flagg: what was to be the tallest building in New York. In the 1890's, Flagg had denounced the growing crop of skyscrapers, and by the turn of the 20th century he was horrified by the darkened streets and raw side walls produced by such buildings. But in the rough and tumble of New York real estate, the opinions of a Paris-trained architect had low priority, and Flagg shifted his focus to reforming skyscraper design. The earliest tall buildings had risen directly from the edges of their plots, presenting bulky fronts and unattractive rears. In a 1907 article in The Times, Flagg lamented the resulting "wild-Western appearance." He urged that skyscraper towers more than 10 or 15 stories high should be set back from the property lines, so that the tower occupied only one-quarter of the lot. All four sides could then be treated architecturally, and "we should soon have a city of towers instead of a city of dismal ravines," as Flagg put it in the article. His proposal also envisioned the concept of transferring air rights from adjacent owners. Begun in 1906, the Singer Building incorporated Flagg's model for "a city of towers," with the 1896 structure reconstructed as the base, and a 65-foot-square shaft rising 612 feet high, culminating in a bulbous mansard and giant lantern at the peak. Flagg reused the earlier building's French-style color scheme of bright red brick and light stone and terra cotta, framing a broad, iron-framed bay of windows rising most of the height of the tower. The lobby had the quality of "celestial radiance" seen in world's-fair and exposition architecture of the period, as the author Mardges Bacon described it in her 1986 monograph "Ernest Flagg" (Architectural History Foundation, MIT Press). A forest of marble columns rose high to a series of multiple small domes of delicate plasterwork, and Flagg trimmed the columns with bronze beading. A series of large bronze medallions placed at the top of the columns were alternately rendered in the monogram of the Singer company and, quite inventively, as a huge needle, thread and bobbin. Singer kept its offices high in the tower, and the bulbous top became one of New York's best known landmarks, even though it was superseded by the 700-foot-tall Metropolitan Life Tower on East 23rd Street in 1909. Flagg's vision of a city of free-standing towers did not get much traction. By the time the Singer Building was completed, another structure, the 34-story City Investing Building, ran plum up against the north side of the Singer plot. Flagg soon became an advocate for skyscraper legislation. The 1916 city zoning law incorporated some of the ideas he had proposed, but it favored the more familiar design of staggered setbacks. Bourne worked with Flagg to produce several other striking commissions, like Bourne's suave country house, Indian Neck Hall, in Oakdale on Long Island, and his retreat in the Thousand Islands, the brooding, Wagnerian "Towers." And Bourne brought Flagg to the Pomfret School in northeastern Connecticut, where the architect designed a moody Norman-style chapel, a crisp Beaux-Arts main schoolhouse and a long ridge-top row of brick dormitories, one of which was named after Bourne, whose son attended the school. When Bourne died in 1919, he left an estate of $25 million. In 1961, the Singer company announced plans to sell Bourne's monument and move to Midtown. William Zeckendorf, chairman of the development firm Webb & Knapp, bought the Singer tower and the rest of the block, hoping to get the New York Stock Exchange to relocate there. That project failed, but United States Steel bought the Singer Building block in 1964 for what became the 54-story One Liberty Plaza, 743 feet high. Demolition of Flagg's building began in August of 1967, as the World Trade Center was rising to the west. In his 1963 inventory "New York Landmarks" (Wesleyan University Press), the preservationist Alan Burnham classed the Singer Building with the Woolworth, Metropolitan Life and other buildings now considered very important. By 1967, Mr. Burnham (who died in 1984) was the executive director of the new Landmarks Preservation Commission. The agency's files contain a meek request from Mr. Burnham asking U.S. Steel to consider preserving the lobby - which didn't happen. "If the building were made a landmark, we would have to find a buyer for it," Mr. Burnham told The Times, adding that "the commission doesn't have a big enough staff to be a real-estate broker for a skyscraper." There were press accounts that much of the bronze was going to be salvaged, and a few pieces do turn up in the architectural antiques trade. So then, what prompted the decision? Well, the tower portion of the Singer Building was about 65 feet square - thus the total area per floor was a little more than 4,200 square feet. The 2.1 million square feet of One Liberty Plaza is laid out on floors that measure about 37,000 square feet. So in the case of the Singer Building and One Liberty Plaza, it boiled down to a matter of square feet. And One Liberty Plaza has many more of them. Copyright 2004 The New York Times Company |

|||||||||||||