|

|

New York

Architecture Images-Lower East Side

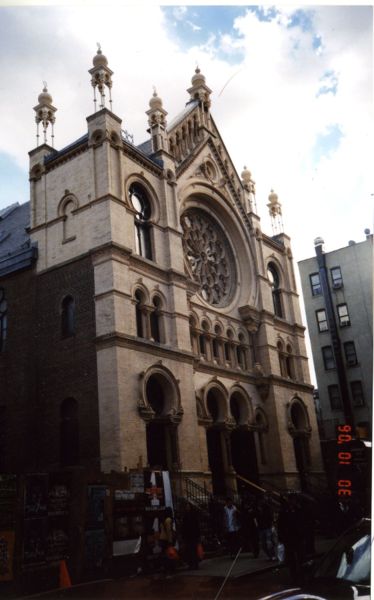

Congregation K’Hal Adath Jeshurun (Eldridge Street Synagogue) |

|||

|

architect |

Herter Brothers. | |||

|

location |

12-16 Eldridge St. bet. Forsyth and Canal Streets. | |||

|

date |

1886-7, restoration 1998, Giorgio Cavaglieri. | |||

|

style |

Gothic, Moorish Revival and Romanesque elements | |||

|

construction |

brick, terracotta | |||

|

type |

Synagogue | |||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

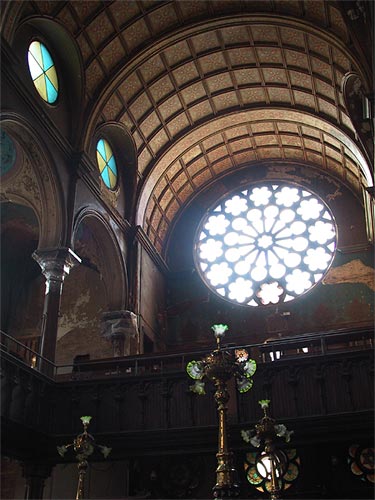

History The Eldridge Street Synagogue was the first synagogue built in the United States by Eastern European Jews. It opened at 12 Eldridge Street in New York's Lower East Side in 1887. The building was designed by the architects Peter and Francis William Herter, the Herter Brothers. The brothers subsequently received many commissions in the Lower East Side and incorporated elements from the synagogue, such as stars of David, in their buildings, mainly tenements.[2] When completed, the synagogue was reviewed in the local press. Writers marveled at the imposing Moorish-style building, with its 70-foot-high vaulted ceiling, magnificent stained-glass rose windows, elaborate brass fixtures and hand-stenciled walls. Thousands participated in religious services in the building's heyday, from its opening through the 1920s. On High Holidays, police were stationed in the street to control the crowds. Rabbis of the congregation included the famed Rabbi Abraham Aharon Yudelovich, author of many works of Torah scholarship. Throughout these decades the Synagogue functioned not only as a house of worship but as an agency for acculturation, a place to welcome new Americans. Before the settlement houses were established and long afterward, poor people could come to be fed, secure a loan, learn about job and housing opportunities, and make arrangements to care for the sick and the dying. The Synagogue was, in this sense, a mutual aid society. For fifty years, the Eldridge Street Synagogue flourished. Then membership began to dwindle as members moved to other areas, immigration quotas limited the number of new arrivals, and the Great Depression affected the congregants' fortunes. The exquisite main sanctuary was used less and less from the 1930s on. By the 1950s, with the rain leaking in and inner stairs unsound, the congregants cordoned off the sanctuary. Without the resources needed to heat and maintain the sanctuary, they chose to worship downstairs in the more intimate house of study (Beth Hamedrash). The main sanctuary remained empty for twenty-five years, from approximately 1955 to 1980. Currently, after extensive renovations, evening services are held in the Beth Hamedrash and daytime services in the main sanctuary. The Eldridge Street Synagogue was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1996. Renovation and reopening On December 2, 2007, after 20 years of renovation work that cost US$20 million, the synagogue reopened to the public. It continues to serve as an Orthodox Jewish synagogue, with regular weekly services, and is also a museum for American Jewish history and the history of the Lower East Side. |

||||

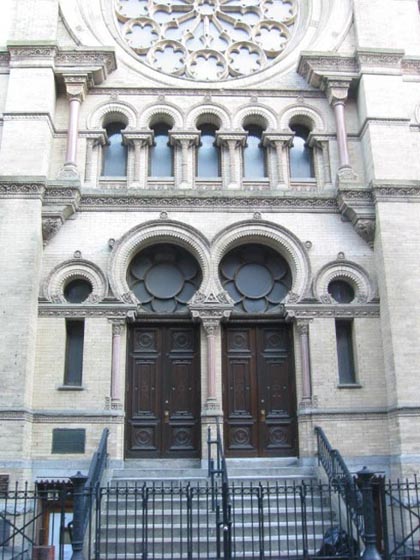

| FACADE -- The Synagogue's facade combines Gothic, Moorish and Romanesque elements. The design uses a numbering pattern that may be drawn from Kabbalah; for example, the twelve roundels of the rose window representing the twelve tribes of Israel and five keyhole windows for the Five Books of Moses. | ||||

|

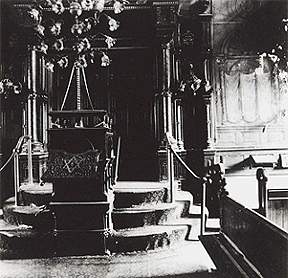

ARK (Aron Kodesh) -- This is

the Holy Ark in which scrolls of the Torah (sifrei torah)

are stored. This one is made of hand-carved walnut. The Ark is

traditionally built on the wall which faces Jerusalem--in the

Western Hemisphere, usually on the East wall. The doors of the

cabinet at Eldridge Street still open with the touch of a finger,

and the red velvet lining dates back to the 1887 opening. Eldridge

Street's Ark is large enough to hold 24 Torah scrolls. Three are now

used by the congregation in their ground floor Beth Hamedrash; the

remainder are kept in a bank vault for safe-keeping. |

||||

|

READER'S PLATFORM (Bimah) --

The table upon which the Torah scroll is read. The location, in the

center of the sanctuary, follows the older European tradition. The

central location is to insure that all can hear the reading of the

Torah, and refers to the location of the sacrificial altar in the

Temple in Jerusalem. In many American synagogues the bimah

is placed in the front of the congregation near the Ark. In

Sephardic synagogues the bimah is generally located in the rear. |

||||

LECTERN (Amud) -- Rabbis and guest speakers would give talks from this pulpit. During the period of the Synagogue's heyday, speeches would probably have been in Yiddish. The music stand below, adjustable to height, was for the cantor (chazzan). With its wonderful acoustics, Eldridge Street was known for sponsoring high quality cantors; tickets to their performances were sold as a way of attracting new members. |

||||

|

EZRAS NASHIM -- The women's

section, located on the balcony or gallery level. In a traditionally

Orthodox congregation such as the one at Eldridge Steet, separate

seating is maintained for men and women. An area of the main

sanctuary, set apart by a curtain (mechitza), would have been

available for older women who had difficulty climbing the stairs. |

||||

| MURALS -- The trompe l'oeil (trick-of-the-eye) mural to the left of the Ark has already been restored. Compare it to the more damaged one on the right side. These murals represent curtained windows looking onto an idealized Jerusalem. Trompe l'oeil effects are used in other parts of the sanctuary, too. For example, wooden column surfaces are painted to look like marble. | ||||

|

||||

| STAINED GLASS -- Most of the stained glass windows have been removed for restoration. Crates on the north side of the sanctuary contain glass at various stages of work. Several windows are complete: a rectangular one in the south stairwell leading to the balcony; a Star of David (magen david) roundel in the rose window on the west facade, keyhole windows on the East and West facades, a large arched window in the southwest corner of the balcony, and a square window on the south side of the sanctuary on the street level. | ||||

| ILLUMINATION -- The sanctuary space was always brilliantly illuminated. Skylights in the roof would allow natural light to flood into the sanctuary throughout the days. The four brass fixtures and glass shades which stand at the corners of the Eldridge Street bimah were originally illuminated by gas and were electrified in the 1920s. Brass fixtures (three on every column) and an enormous chandelier hanging from the chain in the center of the space have been removed for repair and restoration. The menorah and eternal light (ner tamid) will also be returned to their proper places at the front of the sanctuary. | ||||

|

The not-for-profit

Eldridge Street Project, established in 1986, is restoring the landmark

Eldridge Street Synagogue as the focal point of a heritage center on the

Lower East Side. Tours, exhibits and discovery programs keep alive the

memory of Jewish immigrant life at the turn of the last century, explore

architecture and historic preservation, inspire reflection on cultural

continuity, and foster inter-group exchange.

The 1887 Synagogue is the first great house of worship built on the Lower East Side by Eastern European Jews. From its opening, the Eldridge Street Synagogue has been a symbol of the religious freedom and economic opportunity sought by so many immigrants to America. It is the most significant remaining marker of the huge Jewish community that flourished on New York's Lower East Side from the 1850's to the 1940's. Today, it is an inspiration to all those who visit and experience its beauty, rich history and soul. In recognition of the building's architectural magnificence and its role in the American immigrant experience, the Eldridge Street Synagogue was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1996. The Eldridge Street Project was founded by local residents, urban historians and preservationists, who joined together to rescue the building, then in a dire state of deterioration from neglect and water damage and to spearhead a major restoration effort. To date approximately half of an estimated $15 million Completion Campaign has been raised and applied to building improvements and we anticipated completing the Synagogue restoration by the beginning of 2007. The Synagogue is stable and secure, and a master plan has been prepared to guide the restoration. Current work includes the installation of new heating, air-conditioning and ventilation systems to protect the building, as well as access for disabled visitors. A final phase will restore the paint finishes, stained-glass windows, and other aesthetic elements. Alongside this major restoration effort, the Eldridge Street Project has opened the Synagogue to the public, offering tours, lectures, concerts, readings, festivals, family events, and other special programs that interpret the history of the landmark Synagogue and its immigrant neighborhood. More than 20,000 people, representing diverse cultural and religious backgrounds, visit the building each year. They learn about architecture, about American-Jewish history, about their own roots on the Lower East Side and about the common bond of immigration that links so many Americans. |

||||

|

The Eldridge Street Synagogue was built in 1886-87 as a house of worship for K'hal Adath Jeshurun, a congregation of immigrants from Russia, Roumania and Poland (later the congregation merged with another group and added the name "Anshe Lubz"). The congregation, founded in the 1850's, was the first Eastern European Orthodox Jewish congregation in America, and its members had worshipped -- as had thousands of New York Jews -- in tenements, storefronts and former churches vacated by earlier settlers on the Lower East Side. By the 1880s their ranks were bolstered by

the great waves of immigrants who fled the violent pogroms of Europe.

Fearing for their lives and property, they sought a new life in America

and arrived daily on the Lower East Side. Many of the original

congregants had prospered by this time, and so it became possible to

leave behind several temporary shuls for a large synagogue building of

their own. Both Sephardic and German Jews, who

preceded the Eastern Europeans in America, had already established their

own synagogues. Eldridge Street was the first synagogue built to be a

synagogue by Jews from Eastern Europe. The Synagogue's Glory

Years Thousands participated in religious

services in the building's heyday -- so many that, on High Holidays,

police were stationed in the street to control the crowds. The diverse

membership of K'hal Adath Jeshurun exemplified the immigrant spirit, the

resilience, artistry and accomplishments of first generation Americans.

The artists Ben Shahn and Max Gropper, the performers Eddie Cantor, Paul

Muni and Edward G. Robinson, and scientist Jonas Salk were among those

who attended Eldridge Street in the early decades of this century. Throughout the years the Synagogue

functioned not only as a house of worship but as an agency for

acculturation. Before the settlement houses were established and long

afterward, the Synagogue was a place where poor people could secure a

loan, hungry people would be fed, job opportunities were publicized, and

arrangements were made to care for the sick and the dying. It was, in

this sense, a mutual aid society. Years of Struggle The space remained empty for nearly thirty

years, from approximately 1950 to 1980. Without the resources needed to

heat and maintain the sanctuary, the congregants chose to worship

downstairs, as they do today, in the more intimate house of study ("Beth

Hamedrash"). By the 1960s, with the rain leaking in and the inner stairs

unsound, the congregants cordoned off the sanctuary. The Rescue The building was at this point in a dire

state of deterioration. The roof was virtually useless in stopping rain

and roosting pigeons, the foundation had suffered severe structural

damage, plaster and paint fell steadily, and one of two sets of stairs

had collapsed. The Friends secured emergency funds from

public and private sources. They began the process to secure landmark

designations, and organized the emergency stabilization of the

building's exterior, which was completed in 1984. The Eldridge Street

Project, Inc. was established shortly thereafter.

The building's foundation has now been

excavated, reinforced and stabilized; all of the windows have been

sealed with protective Lexan; the exterior has been made watertight; all

rotten and insect-infested structural members have been removed and

replaced; one of the stairways has been rebuilt; six major stained glass

windows have been restored and reinstalled; the building has been fully

pre-wired for the installation of new electrical and HVAC systems; the

Beth Hamedrash has been plastered and painted; new offices and a gallery

space have been created. In 1991, a restoration Master Plan was

completed by the firm of Robert Meadows, Architects. This comprehensive

document provides the blueprint and philosophy for restoration work from

this point on. The next phase of restoration work will make the once

endangered Synagogue fully functional. Once the roof and skylight system

are restored, and new heating and ventilation systems are in place, work

on the aesthetic elements will proceed systematically. Work proceeds when funds are in place to

complete in their entirety one or more of the discrete phases outlined

in the Master Plan. The Eldridge Street Synagogue is a New York City Landmark, is on the National Register of Historic Places, and, in 1996, was honored by the Federal government with National Historic Landmark status. This new status acknowledges that the Synagogue is a national treasure with historical significance for all Americans. The Eldridge Street Synagogue was completed in 1887. It is the first building designed and built to be a synagogue by the Jews from Eastern Europe--from whom 80% of American Jews descend. Eldridge Street was one of the busiest synagogues on the Lower East Side--as many as 1,000 people attended holiday services here at the turn of the century. Membership began to dwindle in the 1920s when U.S. immigration laws stemmed the tide of new immigrants. At the same time, many neighborhood residents were prospering, and public transportation systems made it possible for them to move uptown and to other boroughs. By the 1940s the sanctuary was used only for holidays and special events; most services took place, as they do today, in the beth hamedrash (house of study) on the ground floor. The sanctuary was closed in the mid-1950s. Twenty five years later, a local effort was initiated to rescue the building, then in a dire state of deterioration from neglect and water damage. The not-for-profit Eldridge Street Project was incorporated in 1986 to spearhead the restoration. To date, approximately one-third of an estimated $10 million capital campaign has been raised and applied to building improvements. The Synagogue is now stable and secure. Against tremendous odds, the Eldridge Street Congregation (known as K'hal Adath Jeshurun with Anshe Lubz) has survived, not missing a Sabbath or holiday service in over 110 years. The Congregation meets for services in the Beth Hamedrash downstairs every Sabbath and on Jewish Festival days. Continuing the traditions of Eldridge Street's founders, the Congregation observes Orthodox practice. Congregants do not ride or carry objects on Shabbat, and there is separate seating for men and women. An Aging Synagogue Propels a Philanthropist on a Quest for IdentityWith a $1 Million City Grant, Project at Eldridge Street Shul Sparks a Battle Over Church-State SeparationBy LISA KEYS For years, Roberta Brandes Gratz, the product of an "over-assimilated" family, grew up with barely a semblance of Jewish identity. Coming of age in Greenwich Village, Ms. Gratz had virtually no connection to the vibrant Jewish history of the Lower East Side, a mere 15-minute walk away. But one of her life's defining moments came in 1986 when her friend, attorney Bill Josephson, brought her to the derelict Eldridge Street Synagogue near Canal Street. Mr. Josephson had discovered the synagogue by chance, Ms. Gratz recalled, and he asked her to "come help determine if it was worth the rest of our lives saving it." It was. A well-known urban critic, Ms. Gratz already had an appreciation for historic sites and an intricate understanding of civic landmarking. But as she toiled to rejuvenate the synagogue, she also discovered a renewed sense of Jewish identity. "I walked into this building and felt connected to something I hadn't been connected to," she remembered. "This place added such a wonderful dimension of depth and attachment to the many threads of my life." Ms. Gratz founded the Eldridge Street Project — a non-sectarian, not-for-profit organization — in 1986 in order to preserve the synagogue, the first house of worship in the United States built by Eastern European immigrant Jews. "This is the preeminent landmark of the great Eastern European immigration of the 20th century," said Ms. Gratz. "This is it for the Ashkenazis." Eyebrows were raised last month when the New York City Council and the office of the Manhattan borough president granted $1 million to help restore the synagogue, a move that has provoked outcries about the blurring of the line between church and state. But the congregation housed in the synagogue, K'hal Adath Jeshurun with Anshe Lubz, has no plans to buy a new Torah or build a new social hall. "We're totally separate," said Ms. Gratz, adding that the project is legally distinct from the congregation. "We're totally in charge of the non-religious programs and we have nothing to do with the congregation's programs." Jews have prayed, uninterrupted, at the synagogue for 109 years. For decades, the congregation flourished but, as the Jewish population in the Lower East Side began to dwindle, so did the synagogue's membership. By the 1960s, the bright, spacious main sanctuary had to be cordoned off because of its disrepair and the congregation moved its services to a cramped downstairs sanctuary. Before the restoration of the Eldridge Street Synagogue, the impressive Moorish-style building was in such disarray that it was structurally unsafe, the roof was leaking and one of two staircases had collapsed. Since the synagogue's "discovery," however, millions of dollars have been pumped into its repair. The Project secured the foundation, restored the stained glass windows and recently added a new slate roof with skylights. There is more to go. "While the inside is as terrible as it looks, at least the outside is okay," Ms. Gratz said. Indeed, the main sanctuary is dusty and musty, the wood is worn and the foundation is exposed through the walls. But Ms. Gratz's pride is noticeable as she looks around the room. With its 70-foot ceilings, its powerful sense of history and the sunlight streaming through its many stained glass windows, the main sanctuary in the Eldridge Street Synagogue is breathtaking. Unlike the sanctuary's impressive architecture and intricate embellishments, Ms. Gratz, 60, presents a no-nonsense appearance. Dressed entirely in black, she wears her salt-and-pepper hair cropped short. The author of two books, "The Living City: Thinking Small in a Big Way" and "Cities Back from the Edge: A New Life for Downtown," she is articulate about her involvement with the synagogue, a passion she said she would have "forever." To date, Ms. Gratz has helped raise $4.5 million, funding that has been applied both to programming and to restoring the synagogue to its former grandeur. The money recently awarded by the city, she said, is going strictly toward improving the synagogue's infrastructure. The cavernous interior has raised difficult heating, plumbing and electrical challenges that the Eldridge Street Project hopes to overcome. "We were thrilled to abide by the city's stipulations," said Ms. Gratz. "Heating and electricity are what we need most of all." Others are uneasy about the city's sponsorship of the restoration. "We think that it raises serious constitutional questions," said the executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, Norman Siegel. "From what we've heard it's constitutionally suspect," he said, adding that the use of the landmark status for skirting the church-state divide is "troublesome." Ms. Gratz is not convinced. "I understand the critics' questions when they don't know what goes on in the building," she said. "But once they know what goes on, their criticism evaporates." The Eldridge Street Synagogue, a national historic landmark, is a beautiful structure that helps enhance the civic life of the city, she noted. "This synagogue is the consummate Jewish legacy, but it's now serving the public in a very 21st century way," said Ms. Gratz, citing the variety of groups served by the Eldridge Street Project's educational programs and the project's sponsorship of art installations, panel discussions and community dialogues. "It's not just a synagogue; it's not a museum. This is a hands-on place." |

||||

|

||||

|

links |

http://www.eldridgestreet.org/about_u.htm | |||