|

New York

Architecture Images-Lower East Side

Bialystoker Synagogue |

|

architect |

unknown |

|

location |

7-13 Bialystoker Place. |

|

date |

1824 |

|

style |

Federalist |

|

construction |

made of Manhattan schist from a quarry on nearby Pitt Street |

|

type |

Synagogue |

|

|

|

|

|

| Reading the Book of Esther on Purim 2007 at Bialystoker | |

|

|

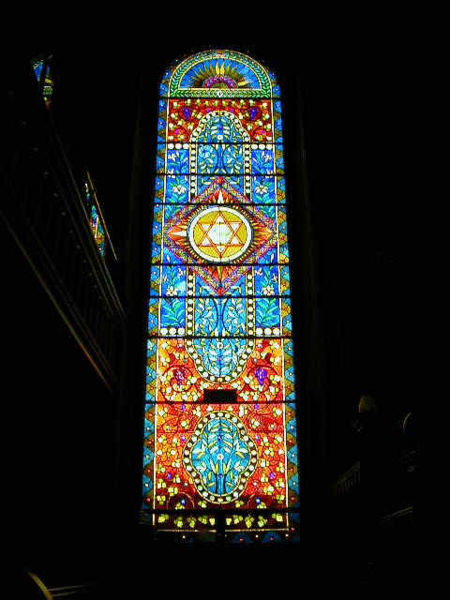

| The magnificent stained glass windows were recently completely recreated and renewed. | |

|

images |

Exterior

Ark from the Left Side

Ark with Blue Tablets of the Law

View from the Balcony

Sivan - Gemini The Twins - The Bialystoker Synagogue

Rachel's Tomb

|

|

The Bialystoker Synagogue at 7-11 Willett Street on the Lower East Side of

Manhattan, New York City, New York State is a Jewish synagogue in a

historic building. History The Bialystoker Synagogue was first organized in 1865 on Manhattan's Lower East Side as the Chevra Anshei Chesed of Bialystok, founded by a group of Jews who came from town of Białystok in Poland. The congregation was begun in a building on Hester Street, then it later moved to Orchard Street, and ultimately to its present location 7-11 Bialystoker Place on the Lower East Side. In order to accommodate the influx of new immigrants from that area of Poland, in 1905 the congregation merged with congregation Hadas Yeshuan, also from Bialystok, and formed the Bait Ha'Knesset Anshi Bialystok (The Bialystoker Synagogue). The newly formed congregation then purchased and moved into The Willett Street Methodist Episcopal Church at 7 Willet Street (now 7-11 Willet Street, later renamed Bialystoker Place). During the Great Depression, a decision was made to beautify the main sanctuary, to provide a sense of hope and inspiration to the community. Architecture The fieldstone Methodist Episcopal Church building was built in 1826 in the late Federal style architecture. The building is made of Manhattan schist from a quarry on nearby Pitt Street. The exterior is marked by three windows over three doors framed with round arches, a low flight of brownstone steps, a low pitched pediment roof with a lunette window and a wooden cornice. The synagogue was listed as a New York City Landmark on April 19, 1966. It is one of only four early-19th century fieldstone religious buildings surviving from the late Federal period in Lower Manhattan. Richard McBee and Dodi-Lee Hecht have both written in-depth articles about the building. As the synagogue is home to an Orthodox Jewish congregation, a balcony section was constructed to accommodate female congregants. In the corner of the women’s gallery a small hidden door in the wall that leads to a ladder going up to an attic, lit by two windows was constructed. When it was first opened, the building was a rest stop for the Underground Railroad movement; runaway slaves found sanctuary in this attic. Present Activity In 1988 the congregation restored the interior to its original splendor, and the former Hebrew school building that is attached, but had become dilapidated, was renovated and reopened as The Daniel Potkorony Building. The magnificent stained glass windows were recently completely recreated and renewed. |

|

|

Shul Hopping: The Bialystoker Synagogue: Historical Relic and Spiritual Future in the Lower East Side By Dodi-Lee Hecht The Bialystoker Synagogue maintains a unique place in Lower East Side Jewish life and history. It has been a permanent fixture of the Lower East Side since it originally opened its doors in its first location on Hester Street, in 1878. At the time, the congregation called itself Chevra Anshi Chesed of Bialystok and was founded by a group of Jews who came from Bialystok in 1873. In 1905, the congregation merged with another congregation of Jews from Bialystok, Hadas Yeshuan, to form the Bait Ha'Knesset Anshi Bialystok (The Bialystoker Synagogue) in order to accommodate the growing influx of immigrants from that area of Poland. The newly formed congregation purchased and moved into a former Methodist church at 7 Willet Street. The Bialystoker Synagogue is still located there although its current address is 7-11 Bialystoker Place. The street name was changed from Willet Street in honor of the synagogue. Today the Bialystoker Synagogue is a popular stop on any tour of this district and is seen as an important historical monument. Concurrently, the Bialystoker Synagogue is still a hub of the area. It is "the most active synagogue in the whole Lower East Side," according to Judah Pattashnick, ritual director. The synagogue features weekly classes for women in Halacha and Hashkafa and weekly Talmud classes for men. Each year the congregation hosts Purim and Chanukah carnivals. The Bialystoker Synagogue also runs a yearly program of legal holiday Torah lectures in which guest speakers are invited to lecture in the morning, following Shacharit and breakfast. The lectures are held on Thanksgiving, December 25, January 1, Presidents Day and Memorial Day. The essence of the Bialystoker Synagogue is its ability to suffer and triumph over adversity. The synagogue has survived the height and decline of the Lower East Side's Jewish community and still remains strong. Pattashnick commented that the synagogue's population suffered during the seventies when Jews were leaving the area. Yet, the synagogue found itself rebounding during the eighties and nineties as young professionals began to move in. Today, Pattashnick estimates that the membership contains 450 families and is still growing. The structure of the synagogue building itself emphasizes the enduring nature of this synagogue and its ability to develop to meet a changing world and, yet, hold onto a rich cultural past. The main sanctuary's beautiful ornaments and garnishes can be traced back to the 1930s, a time most often associated with financial ruin and despair. In the heart of the poorer Jewish area, in a time of poverty and destitution, the Bialystoker Synagogue renovated itself to, according to congregant and creator of the synagogue's website, David Koegel, "provide a sense of hope and inspiration to the community." In 1988, the ceilings were redone to maintain the original Depression Era artwork. However, beautifully crafted stained glass windows were added and the florescent lights in the sanctuary were replaced with chandeliers. The ark that spans the height of the main sanctuary was constructed in Italy and brought to the United States soon after the Synagogue moved to its current location, in 1905. The details of the ark tell the story of Jewish history from the lions' tears, which symbolize the exile, to the eagle crowned with the Torah, which symbolizes the coming of the Messiah. In January 2001, the Bialystoker community suffered the devastating passing of their rabbi of 41 years, Rabbi Yitzchok Aharon Singer. For almost a year the synagogue continued without any rabbinical leader. However, the community maintained itself through this tragedy and today finds itself under the new spiritual leadership of Rabbi Zvi Romm, RIETS graduate. |

|

|

Mazel Tov The Bialystoker Synagogue “And God made the two great luminaries, the greater luminary to dominate the day and the lesser luminary to dominate the night; and the stars.’ (Genesis 1:16).” And it was so, sun, moon and stars, for all time. These basic elements of the order of creation are wonderfully integrated into the elaborate decorations found in the Bialystoker Synagogue on the Lower East Side. What is intriguing is that this synagogue not only possesses wonderful artworks, but also an array of incongruities and surprises that reveals the diversity, creativity and strength of the New York Jewish community. The Bialystoker Synagogue is one of the most exuberant examples of synagogue decoration in the metropolitan New York area. Elaborate floral and geometrical borders ring the walls and landscapes depicting the Land of Israel punctuate the foyer and grace the walls both under and over the balconies. When you raise your eyes heavenward you are confronted with more colorful designs, painted swags, and Corinthian columns everywhere you look. The large painted ceiling creates the illusion of being open to a sunlit sky dotted with puffy clouds and incongruous stars. And ringing this riot of images is an elaborate and beautiful depiction of the twelve signs of the zodiac crowning the main sanctuary. Surely a curious subject matter here since the Midrash (Genesis Rabbah 44:12) clearly states; “No sign of the zodiac has power over Israel.” The Bialystoker is a large shul (seating more than a thousand worshipers), and is one of two New York City Landmark synagogues on the Lower East Side. It has been a mainstay of that Jewish neighborhood ever since the Ansche Kenesset Bialystok (a congregation founded in 1878 of immigrants from Bialystok in Eastern Poland) took possession of the building in 1905. This landmark to the hundreds of thousands of Eastern European Jews who worshipped on the Lower East Side started its life in 1824 as the sanctuary of the Willett Street Methodist Church. The Federal style church was constructed of fieldstone from the Pitt Street quarry only a few blocks away. The building still retains the simple stone façade punctuated by three tall arched windows over the impressive doorways that stand at the top of a set of steps up from the sidewalk. A semicircular window accents the pediment formed by the classic pitched roof. Simple whitewashed walls and ceilings in the interior of the nineteenth century Methodist Church almost certainly reflected this austere exterior. Somber carved wooden pews, some of which are used today in the synagogue, provided the only contrast in this plain Protestant house of worship. When one enters now from the outside there is no way to prepare for the visual clamor within. Three large crystal chandeliers hang from the ceiling over four long sections of wooden pews that lead to the main focus of the synagogue, the massive carved wooden Ark containing the Torah. It rises majestically between two floor to ceiling stained glass windows at the western end of the synagogue. The elaborately carved Ark was brought from Russia and reassembled in its new home. It was restored and highlighted with gold at the same time the entire interior was restored in 1988. This enormous four-year project was accomplished by the master restorer and decorative painter, Paolo Spano from Italy, under the joint supervision of the community’s Rabbi Yitzhok Aaron Singer (z”l) and former synagogue president Norman Davidowicz. The proud theme of the Ark is a succession of three crowns rising majestically over the doors that enclose the holy Torah scrolls. First there is the Crown of Kingship that rests over a carved eagle, symbolic of the royalty of the house of David. In the middle register the Crown of priesthood surmounts a pair of hands shown making the Cohen’s blessing. They are flanked by the Biblical priestly blessing; “ May the Lord bless you and safeguard you. May the Lord illuminate his countenance for you and be gracious to you. May the Lord turn His countenance to you and establish peace for you (Numbers 6: 24-26). Finally the golden Crown of Torah soars to within reach of the ceiling itself. It is the largest of the three crowns and is mounted atop the two Tablets of the Law that radiate a deep blue. These represent the sapphire Tablets of the Law given to Moses on Mount Sinai and are themselves guarded by two gilded rampant lions of Judah. This imposing sculptural ensemble dominates the western end of the synagogue as multi-colored light filters in from the stained glass windows on either side. This is exactly how your gaze is drawn upward until you are captured by the murals on the flanking walls at the ends of the balconies. These two massive paintings, each at least fifteen feet tall, depict deceptively simple scenes of the Western Wall and the Tower of David in Jerusalem. One thinks they are just a random pair of holy places until it becomes apparent that their job is to direct your spiritual attention to Jerusalem, towards which every pious Jew prays three times a day. This may be especially necessary here since the Bialystoker synagogue is oriented not eastward, but rather westward. This incongruity, not uncommon in the grid plan of Manhattan and especially in a building not constructed as a Jewish place of worship, does not present any real difficulty in Jewish law. If one cannot face east towards Jerusalem, then one must face the place of the Torah scrolls and direct your heart to Jerusalem. These paintings serve as wonderful reminders to do so. As one is so elevated in thought and gaze, the elaborate ceiling presents itself. While the majority of the flat ceiling depicts open sky, it is surrounded by a ten-foot wide border. This cove arches up and is filled with a succession of zodiac panels, decorative Italianate cartouches and additional scenes of Israel, all against a warm ochre background. The unknown artist who painted these decorations sometime during the Depression years surely had a strong background in Baroque and Rococo design and ornamentation.

Soft turquoise blue and gentle grays dominate the borders surrounding the zodiac panels that are framed by stately white Corinthian columns. Each symbol of the zodiac is set in a semi-realistic space consisting of a simple depiction of the earth and a pleasant sky above that contains the Hebrew monthly equivalent of the astrological signs. The tantalizing question presents itself again. Why are astrological signs so prominent in the elaborate decorations of an Orthodox shul? Next week we shall examine the "Mazels" of the Bialystoker Shul and try to see what it all means. Part 2 The Bialystoker Synagogue is surely one of the most exuberant examples of synagogue decoration in the metropolitan New York area. The elaborate floral and geometrical borders that ring the walls and the landscapes depicting the Land of Israel in the foyer and near the balconies all lead to the glorious ceiling. There colorful designs, painted swags, and Corinthian columns delight one in the midst of the beautiful twelve signs of the zodiac that crown the main sanctuary. Each symbol of the zodiac, large and visible from every area of the synagogue, is seen in a naturalistic setting in a pleasant sky above the earth. Clearly inscribed are the Hebrew monthly equivalents of the astrological signs. The question presents itself; why are pagan astrological signs so prominent inthe elaborate decorations of an Orthodox synagogue? Mazel Tishre, meaning the star or constellation of the month of Tishre represents Libra that begins September 23rd. Here we start to see how these signs reverberate within the Hebrew calendar. The depiction of scales of balance of Libra reflects that the month of Tishre begins with Rosh Hashanna, the New Year and the awesome Day of Judgment. It is preceded by Mazel Elul, better known as Virgo the Virgin (August 23). An outstretched arm holds up a bouquet of five flowers extended heavenward. Elul is the traditional month of introspection and repentance proceeding the Day of Judgment and symbolically we wish to be considered pure as a virgin, holding forth the flowers of our Torah learning (five flowers; the five books of Moses) in our merit. The springtime ram of Aries is transformed into the lamb of Mazel Nisan, the Hebrew month of Passover and the representation of the lamb sacrifice that always accompanied the holiday seder. Perhaps one of the most sentimental depictions is of Mazel Sivan (Gemini the Twins) that falls in the month of May. Set against a beautiful sky, two parrots are perched facing one another on a leaf laden branch. Sivan is the month of the holiday of Shavuos that celebrates the giving of the two Tablets of the Torah. In this depiction the Torah symbolically sings out with love and harmony. The depiction of Mazel Tamuz (Cancer the crab) as a large lobster is the one vexing representation among the lot. It was clearly the artist’s mistake that the Jewish patrons simply missed. These pious Eastern European Jews didn’t make such fine distinctions among crustaceans. It is fairly clear that the prominent presence of the zodiac in the decorations of the Bialystoker Synagogue is not an expression this congregation’s belief in astrology. Rather its place of honor reflects the importance given to the recurring seasons and holidays that link us to both our history and our daily observances. Alas, these decorations raise other issues in Jewish law. “You shall not make yourself a carved image nor any likeness of that which in the heavens above or on the earth below or in the water beneath the earth (Exodus 20: 4).” Certainly one might be astounded by the lavish, sensual and representational decorations here in the Bialystoker Synagogue considering the stern injunction of the Second Commandment. And yet the tides of Jewish aniconism (hostility to images) have waxed and waned over the centuries of Jewish life. The reality of Jewish concern with images is focused primarily on idolatry. The Mishnah (second century C.E.), Avodah Zarah, Chapter 3, Mishnah 1, is clear in stating that “All images are forbidden because they are worshipped once a year.” And yet we see within a few hundred years figurative depictions and mosaics of the zodiac on synagogue floors in Beth Alpha and at Hammat Tiberias in the fourth century, both in the Land of Israel. Secondarily, the prohibition of images is also concerned with the injunction against imitating the gentiles (“and do not follow their traditions (Leviticus 18:3),” again, because of the underlying threat of idolatry. After the destruction of the Second Temple in 69 C.E. the lure of idolatry is considerably reduced in Rabbinic thinking. We see the great Maimonides (ca.1200) state in his Mishnah Torah, Avodah Kokhavim, 3:10-11 that while; “It is forbidden to make images for (the sake of beauty) even though they are not to be used for idolatry…”nevertheless, “images of cattle and all other living beings, with the exception of man, and forms of trees, grasses, and similar things can be formed,…” The Shulhan Arukh, Yoreh Deah 141:1 (16th century), by the great codifier, Rav Josef Caro, makes even more distinctions of permissibility, stating that, in addition to the previous statement by Maimonides; “There are those who say that images of man and the dragon are not prohibited, except for a complete image with all its limbs…” In addition the serious issue of distraction from prayer arises. The Radbaz (David ibn Abi Zimra, 16th century) comments on the removal of a carved figure of a crowned lion atop the Torah ark in Crete; “Because they look at this image, they do not direct their heart to their Father in heaven.” In spite of these serious issues, some of the most prominent rabbis of the twentieth century, including the revered Rav Moshe Feinstein (z”l) and his sons, Rabbi Dovid Feinstein and Rabbi Reuven Feinstein, have had no problems worshipping in the Bialystoker Synagogue. One thing that becomes clear from the long and contradictory history of Jewish image making is that although images are not absolutely forbidden, there is considerable tension concerning their use. Therefore, how did the Bialystoker murals come to be in an Orthodox congregation? To find the answer we must look to Tradition. Tradition from Eastern Europe, that is. In the classic survey, Synagogues of Europe by Carol Herselle Krinsky (MIT Press, 1985), the design and decoration of the wooden synagogues of Poland are revealed to be the artistic source for the Bialystoker decorations. The author conclusively documents that; “by the late 17th century,…if not earlier, congregations in Eastern Europe were decorating synagogues with abundant images” especially with elaborate arks, carved lions, deer, leopard and eagles and painted murals representing animals, Temple ornaments and landscape views of Hebron, Jerusalem and the Western Wall. Tragically, the vast majority of these wooden synagogues were destroyed by the Nazis during the Holocaust. The loss of this vast artistic heritage is made even more poignant by the survival of its American cousin, the Bialystoker Synagogue. As we sit in contemplation and prayer in the midst of this visual feast, the words of the Talmud (Berakos 32b) come to mind. “ But Zion said: ‘The Lord hath forsaken me, the Lord hath forgotten me’ (Isaiah 49:14). …The Holy One replied: My daughter, in the firmament I created twelve constellations. For each constellation I created thirty hosts; for each host I created thirty legions; for each legion I created thirty cohorts, for each cohort I created thirty maniples; for each maniple I created thirty camps. And to each camp I attached three hundred and sixty-five thousands of myriads of stars corresponding to the days of the solar year. And all of them I created only for your sake.” To the Bialystoker Synagogue I say, Mazel Tov! Richard McBee

The Bialystoker Synagogue, 7 Willett Street, New York, NY Published in The Jewish Press |

|

|

links |

|