|

New York Architecture Images- Midtown

2 Columbus Circle |

|

architect |

Edward Durell Stone & Associates |

|

location |

2 Columbus Circle, Bet. Eighth Ave and Broadway. |

|

date |

1965 |

|

style |

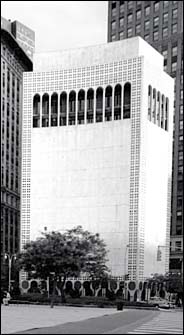

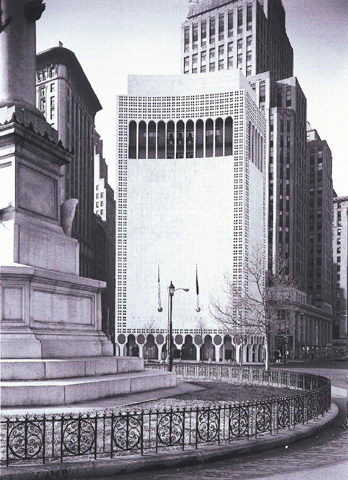

International Style II

romantic modernism "an abandoned work of romantic modernism that has irritated and amused New Yorkers for 30 years" David W. Dunlap |

|

construction |

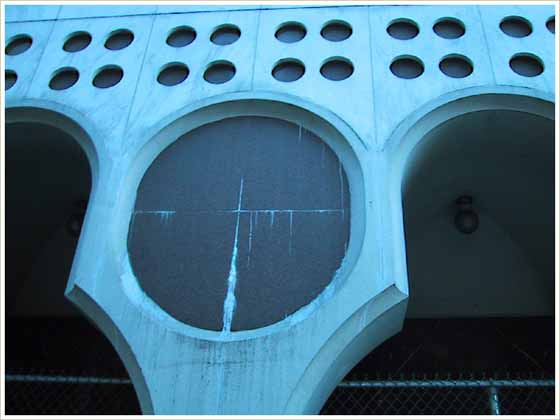

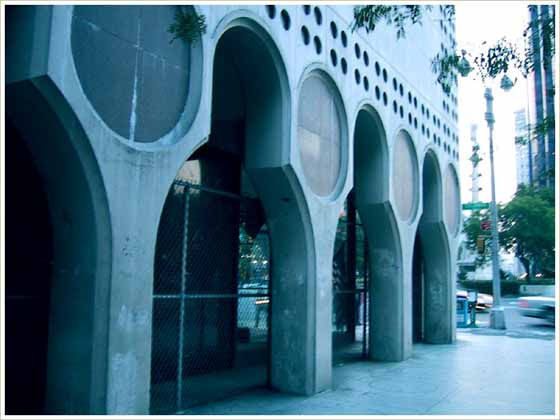

marble cladding- Venetian motifs and a curved façade |

|

type |

Gallery |

|

|

|

|

images |

|

|

"The New York Cultural Center had a short,

brilliant life under the directorship of Donald Karshan, and then Mario

Amaya, who was appointed director in 1972 and turned it into a

Kunsthalle, mounting 150 different shows and attracting large crowds but

also running up big, unrecoverable costs," adding that the museum was

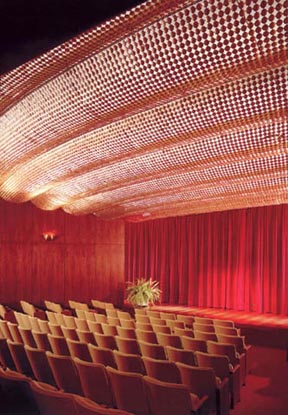

closed in 1975 and put up for sale. "....The walls of the Venetian-inspired vertical palazzo were perforated with porthole-like openings at the corners, base and crown to suggest rustication inspired, according to Stone, by Saint-German-des-Prés, a Romanesque church in Paris. At the ground floor, the building was carried on columns to form an arcade. The top two floors, where the restaurant was located behind a loggia, opened to a view of Central Park. Ada Louise Huxtable likened the overall effect to a 'die-cut Venetian palazzo on lollypops,' while Olga Gueft said that the building's 'red-granite-trimmed, green-marble-lined colonnades, these rows of portholes like borders of eyelet hand-embroidered on a marble christening robe are too winsome for heavyweight criticism.'...The arrangement of a stair gallery wrapped around a core was similar to that of Howe & Lescaze's Scheme Six, proprosed for the Museum of Modern Art in 1931. Filtered natural light was introduced through the glazed perforations at the corners, a technique that worked well with Abe Feder's artificial lighting, while also producing tantalizing glimpses of Central Park without distracting the viewer from the art. The lobby floor was paved in terrazzo, into which were set the discs that had been cut out of the marble when the exterior arches were formed in contrast to the white-painted anonymity of the Museum of Modern Art's galleries. Hartfords' were paneled with walnut and other hardwoods and thickly carpeted or elaborately finished in parquet de Versailles and marble. A pipe organ was included in one of the double-height galleries. Though Hartford's collection did not include any paintings by Gauguin, the ninth-floor Polynesian restaurant, the Gauguin Room, included a tapestry based on one of the French master's paintings." "New York 1960, Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial," (The Monacelli Press, 1995), Robert A. M. Stern, Thomas Mellins and David Fischman |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| image thanks to Jimmie http://www.cornershots.com/ | |

|

|

|

|

|

For 2 Columbus Circle, a Growing Fan Club

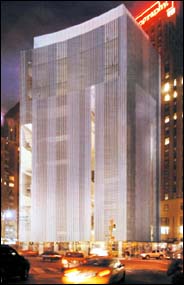

The Landmarks Preservation Commission has refused to hold a public hearing on 2 Columbus Circle, right. By DAVID W. DUNLAP Published: August 18, 2005 THE Landmarks Preservation Commission seems to have painted itself into a corner over 2 Columbus Circle. Its refusal to hold a public hearing on whether 2 Columbus Circle merits landmark status - to receive testimony pro and con, to debate the matter openly, to reach a decision with a vote recorded next to each of the 11 commissioners' names - is based on a consensus reached nine years ago by its designation committee that the building did not possess enough historical or architectural significance to warrant a hearing. But as the date nears for the building's transformation into the new Museum of Arts and Design, a growing number of landmarks commissioners past and present are joining preservationists in urging the commission at least to hear the case for saving it. Nine years ago, the committee's decision was unexceptionable. Two Columbus Circle, which opened in 1964 as Huntington Hartford's Gallery of Modern Art, was designed by Edward Durell Stone in a style most memorably characterized by Ada Louise Huxtable, then the architecture critic of The New York Times, as resembling "a die-cut Venetian palazzo on lollipops." It was a building New Yorkers loved to hate. Hearts began to soften, however, as plans formed to demolish or alter the building, which has been owned by the city since 1980 and has been vacant since 1998. "Something rather wonderful has occurred, by which the building, rarely anyone's favorite in the past, is looking better every day," said Vincent Scully, the Sterling professor emeritus of art history at Yale University, in an Aug. 14 letter asking Robert B. Tierney, the commission chairman, to hold a hearing. "Its own integrity, its uniqueness, the indomitable determination to make a point that produced it, are coming to the fore and are powerfully affecting the way we see it," Mr. Scully wrote. "It is in fact becoming the icon it never was, one about which the city now cares a great deal." The commission itself has acknowledged the redemptive power that the passage of time holds for once-ugly ducklings. In May, it designated the former Summit Hotel at Lexington Avenue and 51st Street, designed by Morris Lapidus and completed in 1961, using language that could be applied almost word for word to 2 Columbus Circle. "Some writers greeted the new hotel with disappointment or amusement, while others viewed it as a disharmonious addition to the streetscape," the commission said. "In subsequent years, however, the hotel attracted an increasing number of admirers." The transformation of sentiment about 2 Columbus Circle has not registered at the commission, where Mr. Tierney continues to rely on the decision made in June 1996 by a four-member committee: the Rev. Thomas F. Pike, Prof. Sarah Bradford Landau, Charles Sachs and Vicki Match Suna. Significantly, Professor Landau, of New York University, has now joined three other former commissioners - William E. Davis, Stephen M. Raphael and Mildred F. Schmertz - in calling for a hearing. "Had there been such a large and broad demand for a public hearing about the building in 1996, I'm not at all sure I would have voted the way I did," Professor Landau said yesterday in an e-mail message. "It is in the long-term interest of the commission to maintain good rapport with the preservation community. Whether the building merits designation is another issue, and should be decided by the current commission." Mr. Raphael said the former commissioners were responding to a July 30 Op-Ed article in The Times by Sherida E. Paulsen, a former chairwoman. She wrote that the decision not to consider 2 Columbus Circle reflected "the professional judgment of the 19 people" who had been on the commission since 1996. BUT Mr. Raphael said, "Some of us neither participated in this decision nor were we asked to acquiesce in it." He and the others wrote that the 1996 decision "does not set a binding precedent" and that strong public interest "may be a valid policy reason" to hold a hearing, which is "not tantamount to granting a building landmark status." Gene A. Norman, a former chairman, and Beverly Moss Spatt, a former chairwoman, have publicly called for a hearing. David F. M. Todd said about his term as chairman in 1989 and 1990, "The spirit - at least then - was, if the public wants a hearing, let's have a hearing." "I'm primarily interested in the law being strengthened, not weakened, by this situation," Mr. Todd said yesterday. Laurie Beckelman, a former chairwoman, directs the new building program at the Museum of Arts and Design, which plans to reclad 2 Columbus Circle with a new facade designed by Brad Cloepfil of Allied Works Architecture. Councilman Bill Perkins, who convened a "people's hearing" on 2 Columbus Circle last month, introduced a bill yesterday to give the Council power to direct the landmarks commission to hold hearings. "People can differ on whether something should be a landmark," he said, "but they can find common ground on the need to have a hearing." At least, they could try. Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company |

|

|

CBS Sunday Morning. Transcript: Form Over Function Aug. 21, 2005 All the neighbors could do was stand there and watch. They say it was no accident the wreckers picked the Friday before the 4th of July when hardly anybody was around to take down the Parmelee House in Kenilworth, Ill. This century-old house was demolished to make way for a so-called "Mc Mansion, CBS News Sunday Morning Correspondent Martha Teichner reports. With no provision in place for protecting significant historical homes here, developers can pretty much do what they want. Once a building's gone, it's gone. Whether we're talking about tear-downs in Kenilworth, the sacrifice of one historic building to save another in St. Louis or, in New York City, the fight over this odd little modernist museum that's not even 50-years-old, we're talking about tough, bruising struggles, right-to- life battles over architecture. A community, like an individual can determine what it wants to be," Richard Moe, president of the National Trust For Historic Preservation, says. "Kenilworth, by not having made a choice to protect these structures is now suffering the consequences," Moe adds. "It's too bad. I hope it's not too late." Forty-five houses have been torn down in Kenilworth since 1993. That may not sound like many, but there are only 820 houses in the whole village. On Lake Michigan, Kenilworth, is one of Chicago's most desirable suburbs. It was founded in 1889. The houses were built by the cutting edge architects of the day, among them Frank Lloyd Wright. "It was one of the first planned communities in the country and we're very proud of that," Tolbert Chisum says. Chisum is the president of the Kenilworth village board. "Candidly, we're probably five years behind," Chisum adds. For years, Kenilworth talked about coming up with a comprehensive plan, but didn't do it. "We want to maintain our suburban community the way that it's been for many, many years," Chisum says. "At the same time, you have to deal with the issues of personal property rights. Tell that to 20-year Kenilworth residents Cameel Halim and his daughter Nefrette. "They took out very large trees," Nefrette says. Asked how he feels when he looks at the missing trees, Cameel replies bluntly, "Sad and angry." There is a certain irony about the public service announcement made by the National Trust For Historic Preservation, considering what happened in St. Louis. The group gave its consent to the demolition, yes demolition, of the historic, landmarked Century Building. Why? You guessed it: so a parking garage could be built in its place. As part of a $77 million jigsaw puzzle of a package to save the historic, landmarked old post office across the street. "I look at buildings as sculpture and it just rips me up to think they would be tearing down that beautiful thing down," artist Alan Brunettin says. Brunettin and television producer Margie Newman live around the corner from the Century building. "Every night. Every night I was out there with a still camera and a video camera. Documented the whole thing," Brunettin says. Newman adds, "It was like watching a murder. It was horrible. It really was horrible. To see and also to know that the ugly politics that had led up to it, and that, in my mind the bad guys had won for all the wrong reasons. It hurt." That's one side of the story. Here's the other. "Sometimes the whole picture needs to be looked at. St. Louis had a very shabby-looking living room," explains developer Steven Stogel. Stogel and fellow developer Mark Schnuck were approached by St. Louis business leaders and politicians ready to raise the money to restore the old post office, vacant since 2000. "It was very obvious that this was the jewel," Schnuck says. Each floor of the post office covers about an acre. "When General Sherman dedicated the building in 1884, he described it as an act of magnificence," Stogel says. It was also a federal courthouse. "Some very significant cases were decided in this courtroom," Stogel adds, citing the break-up of Standard Oil and the teapot dome case. So when the Missouri state court of appeals agreed to move in if the building were restored, it seemed perfect. But the court and the other anchor tenant, Webster University, demanded adjacent parking, meaning the Century Building site. Existing parking lots nearby weren't good enough. "The net effect has been to revitalize the old post office and to revitalize at least ten buildings in the surrounding area," Moe says. But for the National Trust, the bottom line was what it regards as the greater good: a ripple strategy that now drives much of its preservation activity. Moe adds, "Regrettably, we lost the Century. We fought hard for it, with the city, with the developer, with the tenants of the building, and we lost the argument." The National Trust is still hoping to win the argument over 2 Columbus Circle in New York City. It's become the poster child for the preservation battle that's shaping up over what The New York Times calls "baby boomers": post-WWII modernist buildings. Examples are Lincoln Center and the United Nations. Edward Durrell Stone designed 2 Columbus Circle as A&P magnate Huntington Hartford's personal art museum. It has been one of those buildings New Yorkers love to hate ever since it was built in 1964. Vacant for seven years, the city sold 2 Columbus Circle to the Museum of Arts and Design, which intends to transform it inside and out. Holly Hotchner, the museum's director, describes the space as windowless and nasty and a place where Central Park can't be seen except out tiny, Swiss cheese windows. Teichner notes that renovation to the museum must take place both on the inside and outside. "My answer to that is the building failed after five years when it opened originally because it was so deadly as a visitor experience," Hotchner tells Teichner. "To turn this into a truly public space we do have to change it very, very dramatically." Robert A.M. Stern, dean of the Yale School of Architecture, opposes change to the museum. "It's going to be known as the -- unless we have a miracle -- the museum that trashed Ed Stone's most important New York building. Stern is just one of the high-power New York names furious that the city refuses to consider protecting 2 Columbus Circle as is. "You don't kill your old grandma just because of funny breath and bad teeth. And you don't tear buildings down because they don't exactly conform to who you are. That's the whole point." With the average price of office space close to $500 per square foot in New York City -- more than double the national average -- the temptation to take down the glass boxes of the 1950s and 60s and supersize is obvious, unless you're Aby Rosen.. "Here's a late Warhol, 1985. Says, 'Somebody wants your apartment buildings.' I thought it was appropriate," Rosen explains as he gives Teichner a tour of his art collection. Rosen and a partner own and manage something like 6 million square feet of prime New York real estate. But Rosen says buying two modernist masterpieces, Lever House and the Seagram Building, was one of the most thrilling things he's ever done. "We all think that things that are a couple-hundred-years-old need to be protected. It's a wake-up call for all of us that suddenly something that's been only 20-, 30- or 40-years-old might be worthwhile to be protected as well," Rosen says. Lever House, built in 1952, was designed by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. The Seagram Building, completed in 1958, was designed by Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson. In the same way canvas is timeless, so is the glass, so is the stainless steel and the façade of this building. Rosen considers the two buildings as much a part of his art collection as part of his collection of buildings. But, that begs the question: how does a structure manage to survive the changes in fashion and taste not to mention the politics long enough to be appreciated? The answer: sometimes it's just luck. Who could have predicted that the High Line, a long-abandoned elevated railroad that meanders for a mile-and-a-half around and even through Manhattan's industrial past -- a strictly no-trespassing, off-limits to the public kind of place -- would find itself about to be reborn as a $100 million park, like nothing else in the United States. © MMV, CBS Broadcasting Inc. All Rights Reserved. |

|

|

2 Columbus Circle And The Need To Preserve Preservation by Kate Wood November 29, 2004 On the brink of its fortieth birthday, the landmarks preservation law – created two years after New Yorkers were shocked at the needless demolition of the old Pennsylvania Station in 1963 – has preserved more than 1,100 individual landmarks and 22,000 properties in 81 historic districts across New York City. Thanks to the law, and the efforts of the city’s preservationists, New Yorkers and visitors to the city can enjoy brownstone-lined streets of Brooklyn, garden communities of Jackson Heights and such indestructible-seeming architectural monuments as Grand Central Terminal, all of which might not otherwise exist. Today, preservation is a proven tool for stabilizing and revitalizing neighborhoods, maintaining a record of New York’s architectural and cultural history, and creating a tangible link between past and future generations. But while 40 years of landmark preservation is indeed cause for celebration, many preservationists are not in any mood to pop open the champagne. Communities throughout the city are increasingly frustrated by the agency created by the law, the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which seems out of touch with our concerns. A coalition of civic organizations has produced a report, Problems Experienced by Community Groups Working with the Landmarks Preservation Commission, (in pdf format) that cites nine problems with the commission and proposes several avenues for reform. The report was submitted to the City Council’s Subcommittee on Landmarks, Public Siting and Maritime Uses, which scheduled a special oversight hearing for November 29 at 10:00 AM. Among the host of reasons for communities' concern is the commission’s failure to hold public hearings on such buildings as 2 Columbus Circle and St. Thomas the Apostle Church in Harlem, both imminently threatened with destruction or a destructive alteration. These two -- one a mid-century Modern icon by one of America’s most progressive Modernist architects, Edward Durell Stone; the other a work of both architectural and spiritual importance to the Harlem community -- are what Penn Station was forty years ago: igniters. This time, however, the city has a Landmarks Law. The question is, why isn’t it being used? One reason is money. At just over $3 million, the Landmarks Commission’s budget is the smallest of any city agency, and it has fallen precipitously over the past decade, with the staff being cut back significantly. Meanwhile, the commission’s workload has increased by volumes. In any given year, it receives close to 8,000 applications for alterations ranging from cornice replacements to entirely new construction. And with each designation of an individual landmark or district, the workload increases. But, while money is tight, the city cannot afford in architectural and cultural terms to force the agency to scale back its efforts. The mission of the agency is to protect the city’s historical and architectural heritage. Once this heritage is gone, it is gone forever. Another reason the landmarks law isn't being used is politics. The decreased funding for the Landmarks Commission is not merely a symptom of across-the-board municipal belt-tightening. It reflects the city’s priority list, with the real-estate development lobby right at the top. The bias towards large-scale development, which promises quick fixes to perceived urban problems, versus preservation, which can be a slower, more organic renewal process, has an impact not only on the budget but on the political dynamics determining which buildings do – and do not – get considered for landmark protection. Although 2 Columbus Circle is by no means the only source of preservationists’ concern (why else would dozens of groups in communities as varied as St. George in Staten Island and the Upper East Side of Manhattan have leapt to endorse the coalition's report?), it provides a useful case study. The Case For 2 Columbus Circle Robert A.M. Stern is one of the most vocal supporters of preserving 2 Columbus Circle. His credentials go beyond his role as foremost chronicler of New York’s history (Stern is the author of New York 1960, New York 1880, New York 1900, New York 1930, and a forthcoming volume entitled New York 2000). He is one of the most famous architects in the United States, the former director of Columbia University’s acclaimed graduate program in historic preservation, and the current Dean of the Yale School of Architecture. When considering whether to designate a particular resource as an individual landmark or as part of a historic district, the Landmarks Commission frequently cites Stern’s opinions as proof of the resource’s significance. In terms of New York City landmarks, he is clearly an authority. The campaign to save 2 Columbus Circle began in earnest in 1996, soon after the building turned thirty years old and became eligible for landmark designation, when Stern drew up a list of “35 Modern Landmarks-in-Waiting” that was published in the New York Times. Two Columbus Circle, the former Gallery of Modern Art built in 1964 to house Huntington Hartford’s art collection, was included along with the Brooklyn Public Library at Grand Army Plaza and Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. Holding a public hearing to consider 2 Columbus Circle’s merits for landmark designation should have been a no-brainer for the commission. Yet, while the commission has moved to designate a few of Stern’s 35, it has determinedly ignored him on 2 Columbus Circle. It has also ignored the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Preservation League of New York State, both of which included 2 Columbus Circle on their latest “Most Endangered” lists. It has ignored New York Times architecture critics Herbert Muschamp (“The refusal of the New York City Landmarks Commission to hold hearings on the future of 2 Columbus Circle is a shocking dereliction of public duty”) and Nicolai Ouroussoff (“Stone’s design, and the people of this city, deserve more respect than this”). The commission appears unmoved by the signatures collected from over 1,000 individuals and every single major preservation organization in the city, including the Municipal Art Society, the Historic Districts Council, and the New York Landmarks Conservancy, calling for a hearing – not official designation, just a hearing. These advocates are the Silenced Majority, ignored while the new Museum of Arts and Design plans a renovation of the now-vacant 2 Columbus Circle that would destroy many of its distinctive features. The National Trust for Historic Preservation has described those features in this "unorthodox" building as "a marble skin, porthole windows and a street-level arcade that critics have likened to a row of lollipops." But even some critics of the building question the Landmarks Preservation Commission's refusal to give it a hearing. Recognizing the commission’s delinquency on 2 Columbus Circle as part of a larger pattern of negligence, Stern recently issued a statement urging the City Council to exercise its oversight power, “a move necessitated by the continued failure of the city agency to fulfill its important duties.” He went on, “while reasonable people can disagree over the merits of designation, the reluctance of the Commission to simply hold hearings in the face of sustained, vocal, widespread, and indeed unprecedented demand, including the recommendations of two former Chairs of the Commission, is, frankly, inexplicable.” The former chairs to whom Stern refers are Beverly Moss Spatt, a planner who served from 1974 to 1978, and Gene A. Norman, an architect who served from 1983 to 1989. Both have written to the commission to call for a hearing for 2 Columbus Circle, as has Anthony M. Tung, a preservation scholar and former Landmarks Commissioner. Tung wrote, “Simply, in the 26 years of my involvement in preservation matters, beginning with my appointment as a commissioner by Mayor Edward I. Koch in 1979, I have never seen the commission turn its back on such a widely supported and substantive argument for a hearing…Have all of these people suddenly grown ignorant? Entered senility? Gone blind? Or is the commission being arbitrary and capricious?” Arbitrary and capricious behavior by city agencies is grounds for legal action. The report points out that, early in its history, the Landmarks Commission was peppered with lawsuits brought by property owners and developers seeking to overturn the Landmarks Law. Today, a number of lawsuits have been brought by owners and community groups who believe that the commission should have applied higher standards to protect the city’s historic resources. Somewhere along the line, the Landmarks Commission was cast (by its leadership and real estate-lobbied mayoral administrations) in the role of back-room negotiator, transforming what was once a participatory decision-making process into a bureaucratic maze that thwarts meaningful public dialogue. The agency’s ability to determine the future of over 23,000 historic properties throughout the five boroughs has been seriously undermined. The problems experienced by communities seeking to work with the Landmarks Commission reflect both an economic and a cultural shift in the agency’s operations. To try to debate which shift caused which is fruitless. The point is that the commission’s lack of transparency and responsiveness stymies community-based preservation efforts and leads directly to the loss of irreplaceable historic fabric. This loss and the growing chasm between the commission and its natural allies – the citizen-stewards of the historic city – must not become the legacy of our generation. Kate Wood is executive director of Landmark West!, a community group currently leading the effort to preserve 2 Columbus Circle. |

|

|

A small group of elitists pretend to clothe themselves

with disingenuous concern for the common people; and further, expect the

Museum to absorb the considerabale costs to preserve this quirky

builidng that is not even near the ultimate opus of its architect. Yes, how awful that a museum would have to touch up a building that was designed to be....A MUSEUM. Of course, there's no "considerable cost" to sheath the building in glass, because, after all, glass boxes emerge free like tap water from Walter Gropius' dead rectum. Believe it or not, there was a time when buildings were mostly marble, with SOME mirrors, and not the other way around. Enquirer headline: DEAD BAUHAUS ZOMBIES STILL EXERT MIND CONTROL AS TO WHAT MODERNISM SHOULD BE! Hope they pry all of that exquisite wood out of the interior and replace it with proletarian plaster; I mean how can you exhibit FOLK ART on wooden walls? (sarcasm alert) Perhaps the homeless can make bonfires with the wood, safe in the notion that the building is at last bourgeois-proof and utopia is just around the corner! While we're at it, lets put the wrecking ball to that other mostly windowless museum, the Guggenheim. Or at least sheath it in glass (sarcasm alert). Lollipops! Lipstick! Heresy all! Edward Durrell Stone burns in hell for his apostasy, but it is not too late for you, Philip Johnson, to repent and sheath all of your postmodern buildings in glass! (red sarcasm alert) A cautionary tale about another "quirky" "hated" building: "Although the site at the triangular tip of City Hall Park was chosen for a U.S. post office in 1867, the elaborately colonnaded, mansard-roofed building did not open until 1878. After a competition with no winner, a committee headed by A. B. Mullet was formed to design the building. Never liked, it was dubbed "Mullet's monstrosity," and as early as 1920 efforts to demolish it were underway. Despite the city's eagerness to demolish what it considered an eyesore, the subsequent renovation of City Hall Park was uninspired, and the park remains unimpressive." My point is that white marble is a

beautiful, LUXURIOUS material, and that internationalist orthodoxy has

unconsciously brainwashed people that a wall of glass or mirrors is

ALWAYS preferable! Minimalism with marble: bad. Minimalism with glass:

good. WHY? |

|

|

At Columbus Circle, Going Round &

Round Over a Building's Fate

By Linda Hales Washington Post Staff Writer Saturday, May 29, 2004; Page C01  Brad Cloepfil's plan would introduce more light by carving channels into the 10-story building. NEW YORK -- In the annals of preservation, few buildings have generated as quirky a battle as the one raging over 2 Columbus Circle, a beleaguered piece of New York architecture whose intended new owner -- the Museum of Arts & Design -- plans to erase the legacy of a rare American modernist to bolster its own image. At risk is a decrepit 1964 building by Edward Durell Stone, the controversial architect who also gave Washington its John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. The Manhattan building isn't great, and maybe the architect wasn't either. Nonetheless, this week, the National Trust for Historic Preservation declared the structure one of the "most endangered" places in America. The designation raises an impassioned local preservation debate to national stature. The issues -- cultural stewardship and the determination of merit in a building too new to be truly historic -- are played out in many other cities. The Columbus Circle building, which is owned by the city, was designed in the architect's late flamboyant phase. It has a curved facade of white marble adorned with a Venetian-style balcony, portholes and an arcade of abstract arches known from Day One as "lollipops," thanks to architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable, then at the New York Times. Though the 10-story building overlooks Central Park, it is all but windowless. The list of supporters and detractors would make a dinner party worthy of "Bonfire of the Vanities," with writer Tom Wolfe at the head table. (He penned a 4,000-word screed on behalf of preservation last fall in the Times.) Robert A.M. Stern, dean of Yale's School of Architecture, warned that "a world-class landmark is threatened with defilement." National Trust Director Richard L. Moe calls the building "a wonderful work of a great American." Opposition comes from a series of mayors interested in ridding the city of the property for a price and a coterie of progressives who think the building's time has passed. Holly Hotchner, director of the museum formerly known as American Craft (and now saddled with the acronym MAD), describes Stone's work as a "mausoleum." Huxtable, the doyenne of architecture critics, revisited her views earlier this year in the Wall Street Journal. She declared that the building was not Stone's best and figured the structure was probably too far gone to be preserved. The Museum of Modern Art's architecture curator, Terence Riley, believes the newly revived Columbus Circle deserves better. He also opposes invoking the public's goodwill on behalf of mediocrity. In his view, Stone's building has failed on every count. "You're talking about a patient that has been on life support for so long that none of the doctors are still alive," Riley says. Stone designed the building for A&P supermarket heir Huntington Hartford's Gallery of Modern Art, which was to be an alternative to MoMA. The building was savaged by critics, and the museum failed after five years. Ownership passed eventually to the city, which filled it with office workers. Vacant since the late 1990s, the structure now languishes, an eyesore in full view of the gleaming new Time Warner Center. Scaffolding protects pedestrians from the risk of falling marble. Chain-link fencing prevents the homeless from camping between the "lollipops." But for the actions of local preservationists, including what Hotchner calls a "nuisance" lawsuit now being appealed, the museum would have started remaking the building last month. The Museum of Arts & Design is crammed into three small floors of a building opposite MoMA on 53rd Street, with no space to display its permanent collection of more than 2,000 objects. The Stone building offered four times the gallery space, plus room for offices, educational facilities, expanded shop and more -- presuming changes. The museum has raised half the $50 million it needs for the work. Hotchner won't reveal the price it will pay the city. A key point is the freedom to remake the site. The museum has already held an architectural competition, passing up Zaha Hadid, this year's Pritzker Prize winner, in favor of an emerging talent, Brad Cloepfil of Allied Works in Portland, Ore. Cloepfil would preserve Stone's curve and mass but also infuse the dark box with light by carving 30-inch channels into the structural concrete. He says he wants to "extend the memory of that building as an iconic object." The marble facade would be replaced with a layering of custom-made terra cotta. Digital images show a building that is still white, but more ethereal. It's Stone, but it's not. How does it feel to alter a notable American modernist? Cloepfil, who has been called a neo-modernist, responds carefully: "I don't believe it's one of his best buildings. I think Columbus Circle deserves a better piece of architecture." The Trust and its allies disagree passionately. "The board of this new museum should reflect on whether or not a work of architecture is a work of art also and deserves to be protected," says Moe. "I am just astonished frankly that art museum people can take that view." Hotchner is unmoved. The museum, she says, is proceeding apace to "create a great public space." That's what Tom Wolfe remembers. In a conversation this week, he pointed out that, at age 74, he is one of the few voices in the drama old enough to have experienced the white marble elephant in its glorious prime. It was a temple of luxury from a courageous architect revolting against the orthodoxies of his time. Stone's anti-modern decorative streak is best preserved in a celebrated design for the American Embassy in New Delhi. But 2 Columbus Circle is seen by more Americans daily. Wolfe, who excoriated strict modernism in his 1981 book "From Bauhaus to Our House," waxes gleeful about Stone's use of forbidden veneers, ornate railings and regal gold and red carpets on gallery floors. There was also a restaurant and a lounge, which afforded New Yorkers access to views over Central Park. "You felt like you were on top of the world, like all was well in the world," he says. "You were in a white marble building." Little of the glory that Wolfe remembers survives. On a tour two weeks ago with Laurie Beckelman, director of MAD's New Building Program and a former chair of the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission, I took in the postcard view of Central Park framed by Venetian kitsch. The rest of the building exuded the charm of a bunker. Long galleries bounded by a solid curved wall reflected the front facade. From each of seven levels, steps led a half-story down to small, oddly shaped landings, which led to more stairs. By flashlight, paneled walls looked grim rather than deluxe. Pipes had burst, and Beckelman said she had seen water cascading down the stairs. Glimmers of natural light passed through grimy portholes. Only a basement theater, entered through original brass doors, suggested bygone glamour. Beckelman said the museum planned to restore it. Hyperbole is part of the debate as long as Stone's place in history is unresolved. Wolfe calls him "probably the most distinguished American modernist." Hotchner sees him as "relatively significant." Either way, MoMA's Riley cautions, "No architect is so famous that you would say all his buildings are worth saving in perpetuity. Everybody's work is uneven." Stone's son Hicks, who followed his father into the field of architecture, favors preservation, but even his views are conflicted. "Dad was out of fashion for a while," he acknowledges. "Even I at times have been made uncomfortable by the aesthetic of 2 Columbus Circle." Right now, two issues give him pause. Like Moe, he is appalled that "an institution whose central mission is to preserve cultural artifacts is in fact determined to demolish what is probably its most valuable artifact." He also worries that cutting into the structure to add light could destroy the structural integrity of the building. Stone, who died in 1978, is quoted in Paul Heyer's "Architects on Architecture: New Directions in America" as saying: "If our flights of fancy found receptive audiences and each of us were encouraged to be an individual our lives would be enriched. . . . Americans need more than ever to cultivate the open mind." The building is an oddity and the issues are complex. But in the current impasse, open minds would be a better legacy for all. © 2004 The Washington Post Company

|

|

|