|

New York

Architecture Images-Seaport and Civic Center Stalinist Architecture (inspired by the Municipal Building, New York). |

||

|

architect |

various | ||

|

location |

Communist states. | ||

|

date |

1930s-50s. | ||

|

The Municipal Building

in downtown New York impressed Josef Stalin so much that the Moscow

University main building (1949-1953) and its accompanying "Seven

Sisters" was later based on it -- as well as, in general, the whole

grandiose public building style in the Soviet Union and its worldwide

empire. Below are some major examples of this "Stalinist" style. The Municipal building was based on the Giralda Tower in Spain. See Giralda Towers in the United State for a full treatment. "Although many totalitarian regimes toyed with architecture, the architecture of the Stalinist era was not just a plaything of the government. It was not a strange accident of history, but rather a phenomenon of great art with successes and failures, glory and shame." ~Alexi Trakhanov and Sergei Kavtaradze 'Stalinist Architecture' is the term typically applied to the years between 1933 (the date of the final competition to design the Palace of the Soviets) and 1955 (The Academy of Architecture was abolished). In the 1930's and 1940's architecture represents a return to conservatism. Such an approach was not occurring solely under Stalin in Russia. In Germany, under Hitler, architecture had taken a similar turn. As a leader, Stalin created and sustained a a system of repression. Every element of society was under control of the state. Architects ( though not as dramatically as artists and writers) were subjected to such control. Stalin created an intense construction program. To implement his plans, Stalin used prisoners for labor. Because he had total control, many of Stalin's personal tastes became the law. This is evident in may surviving architectural plans. Stalin selected his architects. The architects were considered to be among the elite of society. They lived in lavishly furnished apartment, and built priceless personal libraries, all during a time of poverty and suffering throughout Russia. It was Stalin's goal to "wipe clean the slate of the past...and rebuild the world from top to bottom." Architecture under Stalin reflected several different styles including Neo- Renaissance, classicism, and constructivism. Modernism had been defeated. In keeping with Stalin's total control, and personal taste, Stalin formed a building committee comprised of many of his closest collaborators. As Stalin implemented collectivism, he realized it was necessary to build up the cities. In doing so, he desired to make cities made of "super buildings". On April 23, 1932, the Communist Party Central Committee passed the resolution "on Structural Changes in the Literary and Artistic organizations". The resolution outlawed all independent organization. The formerly independent organizations were forced to form unions where the party could decide was was "fruitful, creative and correct". It was a difficult time for architects because their guidelines were not as clear as those for writers and artists. By July of 1932, all independent organizations were abolished and replaced with the Union of Soviet Architects. On October 14, 1933 the Russian Academy of Architecture was founded. By

the completion of the Komsomolskaya Koltsevaya in 1952, the influence of

Stalin was no longer dominant. Following his death, The Academy of

Architecture was abolished in 1955. This closed the period

typically regarded as the time of "Stalinist Architecture". |

|||

|

images |

|

||

|

the "Seven Sisters" Moscow |

|

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| Description: There are 7 tall buildings in Moscow built in 1950-s - so-called Stalin's Skyscrapers. 1. Moscow University 2. Block of Flats on Kotelnecheskaya enbankment 3. Block of Flats on Krasnaya Presnya 4. Hotel "Lenindradskaya" 5. Hotel "Ukraina" 6. Ministry of Foreign Affairs 7. Ministry of Transport All are worth to see, but first two in a list I consider to be masterpieces of architecture. |

|||

| Click here for a series of images of Unrealised Stalinist Moscow | |||

|

|||

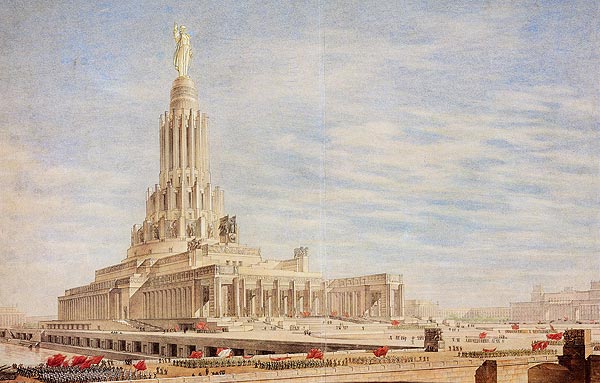

Stalin's 'Seven Sisters'

Washington Post Foreign Service Tuesday, July 29, 1997; Page A10 MOSCOW—To roam in a circle around the base of the skyscraper at No. 1 Kudrinskaya Square is to walk through time. Veterans of the Soviet aviation establishment still stroll laconically around the apartment building's renovated, glassed-in terrace, passing "Club Beverly Hills, a Chuck Norris Enterprise," a posh night spot with a long white limo usually parked outside. Heroes of the Soviet Union who once lived here are commemorated on plaques at the entrances, while the new masters of capitalism park their Mercedes sedans and their bodyguards outside during lunch at the building's stylish restaurant, Le Gastronome. No. 1 Kudrinskaya Square, one of seven tiered, neoclassic Stalin-era towers that define Moscow's skyline, is a testament to Russia's abrupt but dramatic transformation as it struggles to give birth to a free-market system. When the massive tower was built in the early 1950s, there were four elegant food stores, or gastronomes -- for meat, fish, dairy products and bread -- at each of its corners. Modeled on a turn-of-the century Russian food shop in Moscow, they were resplendent with red and white inlaid marble, floor-to-ceiling windows, luminescent chandeliers and mighty central columns. The idea then was to create food "palaces" for the people. But by the time the Soviet Union collapsed at the end of 1991, it would have been hard to recall the original idea. The four corners had become grimy, dreary, smelly shops, the magnificent marble hidden under layers of dirt. Today, one gastronome has sprung back to life as the restaurant, modeled after the original fish shop. Yakov Zhislin, the architect, told the Moscow Times newspaper recently that the design looked to the Italian Renaissance, with wall mosaics based on Florentine models. The stained glass has been restored and the old enclosed cashier's cubicle turned into a telephone booth. Under the giant chandeliers, waiters and waitresses now carry sumptuous meals and desserts such as "Oceans of Chocolate" to Moscow's political and financial power brokers. But the next corner of the building is dark and abandoned. A lone sign promising renovation hangs from a door, its deadline long passed. Inside, the original food cases stand gathering dust. A third former gastronome is a skimpy flea market, still unrestored but with the original chandeliers and marble intact. The last was until recently a branch of Credit Suisse, a Swiss bank, which closed in a dispute with the landlord. The luxurious restaurant, often frequented for lunch by bankers and businessmen, is alien territory to the pensioners who live above it in cramped, one-room apartments. The building originally housed the cream of the Soviet aviation industry, including many famous test pilots. Tatyana Tarasova, 77, who moved into the building in 1955, has not set foot across the threshold of the new restaurant, nor does she want to. "It's hard to get used to the changes," she said, interrupting a stroll. "I've heard in America people go to cafes, and they pay for it. In Russia, it's customary to visit your neighbors, at home. I make food for 20 people!" Such contrasts between old and new are a motif for all seven of the Stalin skyscrapers, sometimes nicknamed the "seven sisters." They include the imposing Moscow State University tower on the Lenin Hills; the aging but revived Ukraine Hotel overlooking the Russian parliament building; and the Foreign Ministry headquarters, near the Old Arbat, central Moscow's lively pedestrian street. Two of the buildings are hotels; two house government ministries; two are apartment houses; the seventh is Russia's most prestigious university. But the blend of old and new is common to all of them. White satellite dishes turned skyward are nestled among neoclassical statues and stone emblems of Soviet power. In its post-Soviet revival, Moscow has become a city of construction cranes, as new steel-and-glass office buildings pop up with growing frequency. But none has challenged the distinctive imprint of these seven buildings on Moscow's contemporary skyline. From miles around, their spires, their silhouettes and their grandiose dimensions overshadow all. The towers owe their design to a monumental building that was never built, the Palace of Soviets. Starting in the early 1930s, planning competitions were held for the proposed 1,410-foot-high structure, which was intended to stand on the banks of the Moscow River where Stalin had destroyed the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in 1931. But despite 25 years of plans and revisions, the gigantic palace never materialized. On the same site today, Moscow Mayor Yuri Luzhkov is rebuilding the cathedral. As in many other realms of art and culture, Stalin pressed Soviet architects into the service of the state, which often meant the service of his personal tastes. In the early 1930s, independent architects were forced to close their practices and work for government design bureaus. Just after the end of World War II, Soviet authorities decided to erect eight tall skyscrapers here in a design similar to that of the Palace of the Soviets. Only seven were constructed. According to the book "Architecture of the Stalin Era," by Alexei Tarkhanov and Sergei Kavtaradze, the architects settled on a terrace-like or tiered construction, often referred to as a "wedding-cake" style, to give each building a sense of "upward surge" toward a central tower. Originally, most of the buildings did not have spires, but Stalin took a fancy to one that did, and soon they all had them -- made of metalized glass and sparkling in the sun. One political reason for adding the spires was to distinguish the towers from American skyscrapers of the 1930s. According to Tarkhanov and Kavtaradze, the design of the buildings and the external decoration recall 17th-century Russian churches, and the ornate exteriors are drawn from Gothic cathedrals. Beyond the towers and tiers, the buildings reflect the gradual transformation of Russia. Take the 1,000-room, 29-story Ukraine Hotel. A seedy place in the latter Soviet years, it has been renovated, and the exterior is now being sandblasted clean, revealing a nearly pink stone under years of grit. The old Soviet practice of having a dzhurnaya, or floor lady, on every hotel floor is also disappearing. Now, "we've got one for every other floor, and even that's too much," said Tatyana Mativsha, the green-smocked dzhurnaya for the Ukraine Hotel's 27th and 28th. In the old days, all guests had to ask the floor lady for the key. Now, computer-coded cards are given out at the front desk. The Moscow State University building was largely constructed by German prisoners of war. According to one legend, a desperate prisoner fashioned wings for himself from two boards and tried to soar off the top of the structure to freedom. The legend says he did not make it. For years, the university tower was the tallest building in Moscow. But it was recently surpassed by one of the the city's shiny new skyscrapers -- this one erected by the Russian natural gas monopoly, Gazprom. Today, the interior of the university building is badly worn in places, but lively, with book stalls chock full of how-to guides on economics and accounting. Alla Tatakonova, 53, a researcher in the chemistry department, recalled that when she came to the school as a student in 1960, the students did not need to work at outside jobs. But in the new Russia, the meager stipends of $15 a month are hardly enough to get by. "Now, everyone is compelled to work," she said. "Life is more expensive." |

|||

|

Hotel Ukraine 1950- 1955 One of Moscow's "Seven Sisters" this building is one of the city's greatest examples of Stalinist architecture. Its spires and mass suggest power and stability. Yet it straddles the line between inspiration and communist utilitarianism. Now that the hard liners have fallen our of power, hopefully it will remain unchanged as an example of the type of mind set that governed Russia for so long. The building, itself, if festooned with propaganda. Huge concrete bundles of wheat curve around the sickle and hammer that was the symbol of the Soviet Union. The hotel occupies the central shaft. In keeping with communist ideals, the flanking rows of 8-10 storey buildings are apartments. Inside the lobby, the ceiling is decorated with murals of Soviet youth enjoying the fruits of Soviet values. 1990 - The Hotel Ukraine is the setting for the film The Russia House featuring Sean Connery and Michelle Pfeiffer. October, 1993 - The rooms facing the Russian parliament are evacuated when the army uses tanks to put down an attempted coup. The hotel faces the parliament building and there was fear that shrapnel, bullets, or debris could hit the hotel. Ministry of Foreign AffairsConstruction of the building began in the 1930s and was completed in 1952. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of External Economic Links and the Ministry of the Russian Federation are located in the offices. Although we didn't go inside, it is worth checking out one of these Sisters up close, to get a good sense of their awesome dimensions (172 metres high). Address:Smolenskaya Ploshchad Directions:Smolenskaya metro; near Old Arbat. |

|||

|

|||

| Moscow Duma | |||

|

|||

| The Metropolitan Hotel. | |||

| Speaking of buildings, Moscow

has its share of interesting structures. Moscow University is a beautiful

old building with two outer towers and a large central tower that is many

stories high. It follows the Stalinist gigantism style and is prominent in

the city's skyline. German prisoners of war are reported to have been

instrumental in its construction. Unfortunately, some central planner liked

it too so there are seven of these buildings throughout Moscow, each of

which is almost the same. It's kind of like having seven Eiffel towers in

Paris.

The old Moscow Hotel is near where we

stayed and features two facades on each end of the face of the building

that are each different. One is extremely stark and the other is nicely

ornamented. The story goes that the architect drew the building to show

each of two possible facades and submitted this for a decision by

Stalin. Stalin approved the drawing without reviewing it, so the

building was built with both facades. |

|||

| Moscow Metro | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| The Moscow's Metro is not the

oldest one in the world, its stations welcomed their first passengers in

1930 only. However, the architectural style and the fascinating design of

many Metro stations deserved the name of the "Underground Palace".

Nearly all stations are reveted with various natural stones having unique

structure and beauty.

The most ancient decorative material used to fascinate the "Underground Palaces" of Moscow is a coarse-grained pink marble from the southern shore of Baikal lake. The age of marble is about 2 billion years, i.e. about half of life of our planet. Marble is used for decoration of about half the area of walls of Moscow Metro. The white marble for Moscow's Metro was brought from the deposits of the Ural Mountains, Altay, Middle Asia and the Caucasus. The black marble from the Urals, Armenia and Georgia decorates the walls of such Metro stations as "Byelorusskaya", "Ploshchad Revolutsii", "Elektrozavodskaya" and "Aeroport". The shades of deep-red marble from Georgia contribute to the solemn beauty of the "Krasnye Vorota" Metro station. Quartzite is the most durable stone material used to decorate the "underground palaces" of the Moscow's Metro. This material is made of the grains of quartz, which is a rather firm and durable material. Thanks to the unique decorative character of quartzite found in Kareliya (the only place, where this material of rich raspberry shade is extracted) the underground hall of "Baumanskaya" station has peculiar solemn architectural style. The semi-precious stones may be found and seen at the oldest Metro stations of Moscow. These are pink rodonite and marble onyx. Marble onyx from Armenia was used to create panels and stone plates at "Dinamo", "Byelorusskaya" and "Kievskaya" Metro stations. Mayakovsaya Metro Station, Moscow. The vaulting of the central hall of "Mayakovskaya" station has 33 mosaics executed to cartoons by famous Russian artist Alexander Deineka. The theme of all mosaics is called "One Day of Soviet Skies". The light character of structures emphasised by the sparkling bends of stainless steel is shaded by red and pink shades of rodonite, a fine semi-precious stone. There are many other Metro stations, which always attract tourists and visitors from all over the world. The bronze sculptures in the hall of the "Ploshchad Revolyutsii" station show the way up, right to the City Centre, Red Square. If there is no guide accompanying you in your "underground tour", first find some valuable information about Metro in the Section called Municipal Transport.

|

|||

| Warsaw | |||

|

|||

| The Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw. | |||

| Armenia | |||

|

|||

| The Stalinist train station in Yerevan, Armenia. | |||

| Azerbaijan | |||

|

|||

| bulgaria | |||

|

|||

| Stalinist government building in Sofia, Bulgaria. Interestingly the Giralda Tower is used as was used on the Russian Orthodox church two centuries previously. Both repesented Russian Imperial power- one religious, one ideological. | |||

| Pyongyang | |||

|

|||

| Photos of the central train station in Pyongyang. The slogans on the roof read "Long live the Great Leader Comrade Kim Il Sung; long live the glorious Workers' Party of Chosun." | |||

| Prague | with thanks to Dan Drotar | ||

|

|||

| Riga | with thanks to Dan Drotar | ||

|

|||

| Shanghai | with thanks to Dan Drotar | ||

|

|||

| East Berlin | |||

Monument to the Unknown Russian Soldier. |

|||

| From

Besarinplatz to Alexanderplatz: Karl-Marx Allee and Stalinist architecture

in the GDR

"The old center of Berlin, a mirror of the history of our nation, and as a whole a typical product of capitalistic-anarchic city development, was destroyed through the criminal politics of German imperialism and militarism. So sank many cultural monuments in ashes, that generations of great builders with the industry of our forefathers had built. . . . We Berliners who love our city, will determine how the future of Berlin will look like" (Landesarchiv Berlin C Rep 120 - Nr. 1975 "Rund um Alex: Information für Presse und Information" This study goes from Besarinplatz in Friedrichshain to Alexanderplatz in Mitte, going by way of the famous Karl-Marx Allee (formerly known as Stalinallee), christened the "First Socialist Street of the Socialist State" by the GDR. Besarinplatz is an example of what I would term "Late-Plattenbau" construction. It appears to have been built in the late 1980s, as its construction is very similar to that of Ernst Thälman Park, which was finished just as the GDR collapsed in 1990. The typical straight lines of GDR industrial construction are broken up a bit with brick facades and balconies. Besarinplatz is named after General Nikolai Besarin of the Red Army - a favorite figure in Berlin for efforts to feed the city before his death in a motorcycle accident. Efforts to rename the place after 1990 were vigorously fought by Berliners, as well as the Russian embassy. Karl-Marx Allee, formerly Stalinallee, offered up a vision of the socialist future. According to Brian Ladd in Ghosts of Berlin, it was also a vision of totalitarian control with strict order and demonstration of state power. Unfortunately, it was also terribly expensive, meaning that this instance of city planning was never repeated in the German Democratic Republic. The area is now a historical preservation district, and a great deal has been repaired and revitalized. The apartments were, and continue to be, highly desired and while the area was derided during the Cold War, it has achieved a certain degree of respectability. To be honest, if socialism had looked like this, it might not have been that bad. Of course, it didn't and its construction led to the most significant revolt in the history of the GDR when workers from the project threatened to strike. The threats turned into a protest and eventually the Soviet crackdown of June 17, 1953. The last section shows what came after Stalinist classicism with industrial construction, as in the other section on Marzahn and the Landsberger Allee. It was a bit more interesting than the endless blocks of apartment buildings, but was essentially a different ordering of the building blocks. Several competitions have been held on the future of Alexanderplatz, most of which envision the same kind of high-rise center at Potsdamer Platz. Dominating Alexanderplatz is the Kaufhof department store, the Forum Hotel and, on the other side of the train station (not officially on Alexanderplatz, but still there), the Television Tower.

|

|||

|

notes |

stalinist

high-rises back in vogue

By Susan B. Glasser  MOSCOW - Moscow developers in the 1990s built great towers of glass,

hoisted dizzying neon signs along once-gray avenues and invested millions of

dollars in shimmering new buildings whose main architectural style was best

described by one critic as "late Las Vegas."

MOSCOW - Moscow developers in the 1990s built great towers of glass,

hoisted dizzying neon signs along once-gray avenues and invested millions of

dollars in shimmering new buildings whose main architectural style was best

described by one critic as "late Las Vegas."

But tastes have changed since the excesses immediately following the breakup of the Soviet Union, when anything Soviet was out and anything that smacked of Western-style modernism, no matter how tacky, was in. Not so in the Russia of President Vladimir Putin, whose political slogans of stability and restoration of Soviet-era symbols have been mirrored in the changing landscape of Europe's largest city. The design concept of the moment is what architects here call neo-Stalinism, in homage to the style decreed by Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, who reshaped Moscow after World War II. Seven imposing skyscrapers and a host of shorter cousins were built in Stalin's time, meant to emphasize the grandeur of the victorious Soviet state. In the capital, where demand has soared for pricey apartments and construction sites ring the city center, new buildings evoking the Stalin era are selling out, according to developers and real estate agents. One such palace for the new rich is called Nostalgia. "This is what remains from Soviet times for me personally," said Tatyana Samuelyan, one of Nostalgia's first residents. Another is Triumph Palace, a massive tower rising just off Leningradskoye Shosse, marketed as the long-planned but never built eighth Stalin skyscraper. The building's luxurious accouterments include an in-house fitness center, underground parking and direct Internet hookups for the capitalist era, but its design is copied directly from the workshops of socialism. Its spire went up last December, making Triumph Palace, at 264 meters, the tallest residential building in Europe. A year before completion, its 960 apartments have all been snapped up. The new buildings, said architecture writer Yevgenia Mikulina, play off buyers' "subconscious connection with wanting to be great and glorious and respectable." But the buildings, many of which were conceived soon after Putin's rise to power in late 1999 and are just now opening, are not only an echo of the changed political and cultural climate. More subtly, they reflect Russian notions of what constitutes status. In terms of Moscow addresses, the seven Stalinist skyscrapers were considered the height of unattainable luxury, with solid construction, relatively luxurious materials, high ceilings, classical details and prime locations. The country's best architects designed them; Stalin personally approved key details of their construction. Reminiscent of the Art Deco skyscrapers of New York, the Stalin-era versions also boast Gothic towers and spires ordered by the Soviet leader. Only the best-connected Muscovites linked to the party elite could ever hope to obtain an apartment in one. Even decades after they were built, the Stalin-era buildings maintained their aura of exclusivity - especially when Russians compared them with the shoddy concrete block edifices that proliferated in the 1960s and 1970s, cookie-cutter compounds that now dominate in Moscow and other Russian cities. The new buildings in the Stalin style explicitly appeal to consumers who have the money to buy what previously could not be bought at any price - and with modern conveniences. Mikulina, deputy editor of the Russian edition of Architectural Digest said: "It's a dream come true, something which looks really old and wonderful but it's new, the water is working, you have the Internet and modern interiors." POST-SOVIET ARCHITECTURE DOMINATED BY REMAKES MOSCOW, July 22 /from RIA Novosti's Anatoly Korolev/ - The last seven guests have just checked out of the Moskva Hotel, opposite the Kremlin. Built to architect Alexei Shchusev's designs in the Stalin era, the city's largest (1,033-room) and cheapest (with suites at a mere $200 per night) hotel is now to be demolished. The Moskva Hotel's exterior may still be admired by the lovers of Stalinist architecture, but even they find the interior outdated. Some also argue that a plush hotel would be more appropriate on this vantage spot than the three-star Moskva. According to City Hall officials, a new, five-star hotel will emerge on the site in thirty months. They say it will have 400 rooms, a conference hall, and an underground car park with 2,000 spaces and that its courtyard will be covered with a transparent dome to protect its tropical garden from Moscow's extreme wintertime temperatures. But the gimmick behind this ambitious project, estimated at $150 million, is that the new building's exterior is going to be an exact replica of Shchusev's original. No other urban community has ever attempted anything similar with its architectural landscape. Indeed, one can hardly picture Berliners razing their Reichstag only to replace it with a copy or the Parisians demolishing the Louvre for this same purpose. But to the Muscovites, an architectural remake is nothing new. The first experience was the 1934 demolition of the riverfront Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, built in 1889 to commemorate Russia's victory over Napoleon. The Soviet authorities' ambition was to erect a palace five hundred metres tall, with a huge statue of Lenin on the top. Great names in world architecture, including Le Corbusier, took part in the design contest. The Soviet architect Boris Iofan's submission was eventually picked, despite its ugliness. The construction was interrupted by WWII; after the war, the Soviet leaders' imperial spirit subsided somewhat, and the epic ended up in a farce, with an outdoor swimming pool built instead of what was intended to be the world's highest structure. A local legend claimed that a bearded monk could often be seen in that pool, trying to exact his revenge by drowning swimmers around him. Post-Soviet Russian architects came out with an updated version of the cathedral, adding to the original layout a hall for Synod gatherings and an underground museum. The renewed church was unveiled with much pomp, starting the tradition of "blockbuster remakes" in Russian architecture. The Amber Room recently reopened at Tsarskoye Selo, outside St. Petersburg, is a later example of the trend. And the most recent attempt to replicate a ruined structure has been made in another Petersburg suburb, Strelnya, whose newly built Constantine Palace follows Peter the Great's designs even more carefully than the original. When inaugurating the lavish building, erected to coincide with St. Petersburg's 300th anniversary celebrations, President Vladimir Putin promised to the numerous foreign dignitaries in attendance that democratic Russia's architecture would be as sumptuous as that created by the Russian monarchy. This trend to recreate rather than just create has affected Russian sculpture, too. Work is currently underway to remake Vera Mukhina's famous steel statue at the entrance to what was formerly known by the acronym VDNKh (or the Exhibition of the National Economy's Achievements). Representing a worker with a hammer and a farm girl with a sickle, the now-rundown masterpiece of Socialist Realism is to be refurbished and placed onto a higher pedestal-just like the one upon which the sculpture rested at the World Expo in Berlin before WWII. Sitting on the 30-metre platform, "The Worker and The Collective Farm Girl" faced the equally imposing representations of an eagle and swastika at Nazi Germany's pavilion. The French architect Dominique Perrault has been able to sense the new Russian trend. This may be part of the reason why his design of a wing for St. Petersburg's Mariinsky Theatre has been given preference over nine other submissions from established Russian and foreign competitors. Unlike his counterparts, Perrault does not seek to adjust the existing architectural landscape to his own vision, but preserves the old surroundings as they are, even the iron-like Culture House, part of the Soviet cultural legacy. He just covers the Marrinsky and the adjacent buildings with a glistening net of gold. Dubbed by locals "golden lapot" [the lapot is a type of Russian rustic footwear, made of birch bark], the Frenchman's design is meant to please modern-day Russian rulers, dreaming back to their country's golden imperial past. The construction of a new Moskva Hotel is about realising this same ambition, albeit on a slightly smaller scale. |

||

|

links |

|||