|

New York

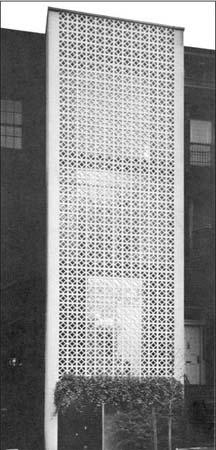

Architecture Images-Upper East Side Edward Durrell Stone House |

||

|

architect |

Edward Durell Stone | ||

|

location |

130 East 64thth Street, Bet. Park And Lexington Ave. | ||

|

date |

1956 | ||

|

style |

International Style II | ||

|

construction |

Concrete breeze-block grill | ||

|

type |

House | ||

|

|

|||

|

images |

|

||

|

|||

|

|

by Kristin Miller In a staid district of late-nineteenth-century town houses on New York City's Upper East Side, the romantically lacy, stark-white concrete grille in front of the Edward Durrell Stone house has raised a ruckus since it was constructed in 1956. When the grille first appeared at 130 E. 64th Street, more than 20 years before the Upper East Side Historic District was created, Stone had only his neighbors and architectural critics to contend with (neither group was pleased). Nowadays, in a landmark district, such an alteration to a facade would be absolutely prohibited. Yet the controversial little town house has become an unofficial landmark of its own--and largely for the addition that many still consider an eyesore. This turnabout has led some of the city's big guns to take the surprising stance of defending the screen on its architectural merits. According to longtime New York City Landmarks Commissioner Thomas Pike, standards for landmark status have changed significantly over the years. During the nineteenth century, preservation decisions were mostly dictated by politics. (There's even a church in Queens that missed the first wave of landmarking because it was popular with the wrong side during the Revolutionary War.) In the early twentieth century, the focus shifted to preserving works of "import." According to Pike, "Now we're preserving not just beautiful buildings, not just those connected to history, but the fabric of history itself." So how did the Stone house almost become an official landmark? Stone is a hard architect to love, particularly in aesthetic terms. His brand of romantic Modernism has yet to come back into fashion, and, according to one New York architect, "Many people who love Modernist architecture don't like Stone." This is probably why, when the facade fell into disrepair in the late 1980s, Stone's widow removed the screen--and promptly got slapped with a Landmarks violation penalty, which halted all reconstruction efforts and made selling the property difficult. These days, such a violation can incur fines of as much as $250 per day. In 1992, Maria Stone applied to the commission for release from the violation through a "certificate of no effect." But some powerful voices spoke up for the white grille. Unbeknownst to the Stone family, Robert A.M. Stern, a strong advocate for the preservation of Modernist architecture, asked the commission to "rise above the inevitably changing winds of fashion... and preserve an important architect's ingenious, if controversial, solution to the problem of town house design." Stern's voice won out and the violation remained in effect. Stone's son, Benjamin Hicks Stone, an architect himself, proposed several of his own designs as alternatives, but the commission wouldn't accept anything other than the reconstruction of the original design, as unpopular as it was. According to Pike, "Preservation means telling the whole story of the American experience accurately and completely," which might be the single best argument for saving the unfashionable Stone style. The red velvet and white marble interior certainly contained a glamorous version of the American experience, with hostess Stone serving cocktails to the likes of Sophia Loren, Jack and Jackie Kennedy, and Frank Lloyd Wright. It's a roster of figures whose popularity has waxed and waned, perhaps as much as that of the man behind the wild, white concrete grille. Thanks to http://www.metropolismag.com/index.html |

||

|

notes |

Set in one of

Manhattan’s most desirable neighborhoods where elegant brownstones on tree-lined streets epitomize old world New York. This four-story townhouse was the home of Modernist architect Edward Durell Stone and his family. In 1956 Stone covered the Victorian-era brownstone with a façade made of decorative concrete blocks. Stone had previously used the decorative blocks in his design for the New Delhi Embassy and, while it gave the family some privacy by shielding the façade’s glass curtain wall, it also prevented natural light from entering the north-facing rooms. Over time, the reinforcing steel that held the masonry blocks together had rusted, substantially cracking the façade, while the otherwise lacy effect of the grille’s open-work pattern was marred by pollution that collected in its deep interstices. As the deteriorating concrete became a safety hazard, the grille was eventually removed, exposing the house’s glazed façade underneath and allowing light to flood the relatively dark interior spaces. Despite these advantages, the New York City Landmarks Commission objected to the removal of the grille in an ironic effort to maintain the “integrity” of the Upper East Side historic district. The architect’s son, Hicks Stone, proposed an alternate solution. Rather than replace the decorative grille, Stone, who had grown up in the house proposed a design that captures the spirit of urban townhouse living and pays homage to his father’s Modernist legacy. Glass is the catalytic element in this precise composition that offers a 20thcentury take on traditional townhouse bay windows without resorting to overt historical references. Stone opened up the front elevation with three-stories of projecting windows set within alternating bands of rough and smooth limestone, a nod to the city’s luxurious residential facades. The horizontal banding of the floor-to-ceiling windows relieves the structure’s strict vertical orientation. The glazing is set in painted steel frames whose finish matches the thin, Corten steel spandrel beams that will weather to a gray patina over time and enrich the play of rough and smooth, transparent and opaque materials. Capping the design is a roof canopy that recalls E.D. Stone’s façade for the Museum of Modern Art yet gives the home a domestic form. |

||

| Architect Edward Durell Stone's 1956 "neo-Baroque" 130 East 64th Street house was also a tough sale. The concrete façade was taken down by his widow, then rebuilt by order of the Landmarks Preservation Commission before it could be sold last year for $2.3 million. "Atypical" houses, says Sharon E. Baum of Corcoran, who sold it, "take longer to sell, but people like buying something that's a name property." | |||

|

links |